Rudolf Steiner: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

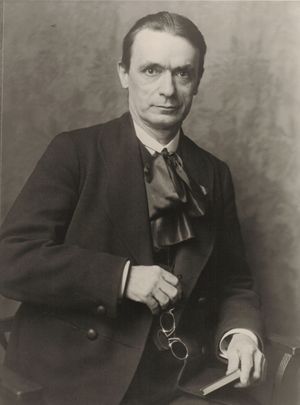

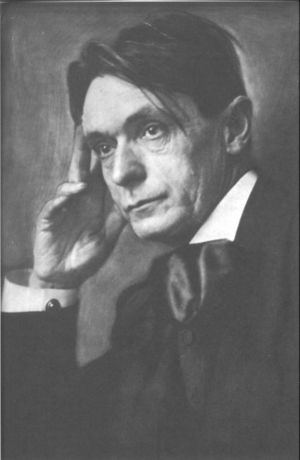

[[File:Steiner original.jpg|thumb | [[File:Steiner original.jpg|thumb|Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925)<br>[[File:Steiner Autograph.gif|center|200px|Signature of Dr Rudolf Steiner]]]] | ||

'''Rudolf Steiner''' (born 25 or 27 February 1861 in Kraljevec, then | '''Rudolf Steiner''' (born 25 or 27 February 1861 in [[Kraljevec]], then [[w:Austrian Empire|Austrian Empire]], now [[Donji Kraljevec]] in [[w:Croatia|Croatia]]; † 30 March 1925 in [[Dornach]] near [[w:Basel|Basel]]), was an Austrian [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe|Goethe]] scholar, philosopher, and [[spiritual researcher]]. He opened a new, forward-looking scientific approach to the [[spiritual world]] through the [[anthroposophy]] he systematically developed as a [[science of the spiritual]] from 1900 onwards, based on the [[observation of thinking]] according to the scientific method, which he had already presented in detail in his [[Philosophy of Freedom]] published in 1894 and in the second part of which he founded an [[ethical individualism]] based on the self-aware free [[I]] of [[man]], which must not be confused with his mere [[ego]]. | ||

With [[eurythmy]] Steiner created a new art of movement and with the [[Goetheanum]] in Dornach as the seat of an independent [[School of Spiritual Science]] and through other buildings a new, organic architectural style. To a considerable extent he gave instruction in the art of recitation and declamation. The [[Waldorf school]] made possible more natural learning, [[biodynamic agriculture]] nourished life, the idea of the [[threefold social organism]] was to make possible the principle of freedom in spiritual life, equality in legal life and fraternity in economic life. Together with [[Ita Wegman]], Steiner created [[anthroposophic medicine]]. He also gave suggestions to experts in other arts and the [[natural sciences]], mostly at their request. | |||

== Life and work == | |||

=== Childhood === | |||

[[File:Kraljevec_Steiner_family_home.jpg|thumb|300px|The presumed home of the Steiner family in Donji Kraljevec. Rudolf Steiner's birthplace, on the other hand, was presumably the station house on the southern railway line, which was destroyed in [[w:World War I|World War I]].]] | |||

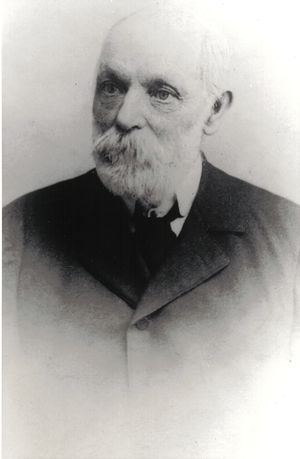

[[File:Johann Steiner.jpg|thumb|Johann Steiner (1829-1910), Rudolf Steiner's father.]] | |||

[[File:Franziska Steiner.jpg|thumb|Franziska Steiner, née Blie (1834-1918), his mother.]] | |||

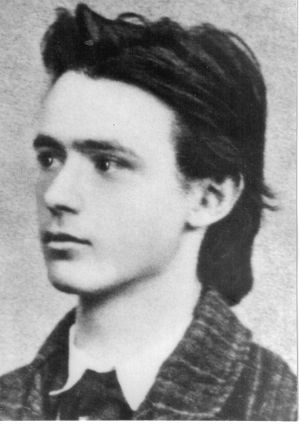

[[File:Rudolf Steiner as Abiturient 1879.jpg|thumb|Rudolf Steiner as a high school graduate (1879).]] | |||

Rudolf Steiner's birthplace is [[Donji Kraljevec]], a small village in northern [[w:Croatia|Croatia]] not far from [[w:Čakovec|Čakovec]]. The village is located on the so-called ''Mur Island'' between the [[w:Mur (river)|Mur]] and [[w:Drava|Drava]] rivers, which Rudolf Steiner also liked to call the "Two Rivers Land". His parental home was free-spirited, his father, '''Johann Steiner''' (1829-1910), was a railway official; to his mother '''Franziska Steiner''', née Blie (1834-1918), he always remained in a loving and soulful relationship. Both parents came from the [[w:Lower Austria|Lower Austria]]n [[w:Waldviertel|Waldviertel]], where they also returned after the father retired. Rudolf Steiner had two younger siblings: '''Leopoldine''' (1864-1927), who lived with her parents as a seamstress until their death, and '''Gustav''' (1866-1941), who was born deaf and was dependent on outside help throughout his life. His father had previously worked as a forester and hunter in the service of Count Hoyos of [[w:Horn, Austria|Horn]] (a son of Count Johann Ernst Hoyos-Sprinzenstein); when the latter refused to give him permission to marry in 1860, he resigned from the service and found employment as a railway telegraph operator on the southern railway. In «[[The Story of My Life]]» Steiner writes: | |||

{{GZ|My parents had their home in Lower Austria. My father was born in Geras, a very small town in the Lower Austrian Waldviertel, my mother in Horn, a town in the same area. My father spent his childhood and youth in close connection with the Premonstratensian monastery in Geras. He always looked back on this time of his life with great affection. He liked to tell how he had served in the monastery and how he had been taught by the monks. He was later a hunter in the service of the Count of Hoyos. This family had a property in Horn. That's where my father met my mother. He then left the hunting service and joined the Austrian Southern Railway as a telegraph operator. He was first employed at a small railway station in southern Styria. Then he was transferred to Kraljevec on the Hungarian-Croatian border. During this time he married my mother. Her maiden name is Blie. She comes from an old Horner family. I was born in Kraljevec on 27 February 1861. - That's how it came about that my place of birth is far removed from the region of the Earth from which I come.|28|10}} | |||

The family moved several times: in 1862 to [[w:Mödling|Mödling]], a year later to [[WikipediaDE:Pottschach|Pottschach]] and in 1869 to [[w:Neudörfl|Neudörfl]]. A deep mystery was presented to him by a railway carriage that caught fire: | |||

{{GZ|Once there was something quite "shocking" at the railway station. A railway train with freight was whizzing towards us. My father looked towards it. A rear wagon was on fire. The train crew had not noticed anything. The train came up to our station on fire. Everything that was happening made a deep impression on me. A fire had been started in one of the carriages by a highly inflammable substance. For a long time I wondered how such a thing could happen. What those around me told me about it was, as in similar matters, not satisfactory to me. I was full of questions and had to carry them around with me unanswered. So I became eight years old. - When I was eight, my family moved to Neudörfl, a small Hungarian village.|28|20}} | |||

A supernatural experience from that time made a particularly deep impression on him: | |||

{{BZ|But the boy also had something else to look forward to. One day he was sitting all alone on a bench in the waiting room. In one corner was the stove, on a wall away from the stove was a door; in the corner from which one could see the door and the stove sat the boy. He was still very, very young at that time. And as he sat there, the door opened; he must have thought it natural that a personage, a woman's personage, should enter the door, whom he had never seen before, but who looked extraordinarily like a member of the family. The female personality entered the door, walked into the middle of the room, made gestures and also spoke words that can be rendered in the following manner: "Try to do as much as you can for me now and later!", she spoke to the boy. Then she was present for a while, making gestures that cannot disappear from the soul once one has seen them, went towards the oven and disappeared into it. The impression made on the boy by this event was very great. The boy had no one in his family to whom he could have spoken of such a thing, for the reason that he would have heard the harshest words about his stupid superstition if he had told anyone about this event. The following happened after this event. The father, who was otherwise a quite cheerful man, became quite sad after that day, and the boy could see that the father did not want to say something that he knew. After a few days had passed and another member of the family had been prepared in the appropriate way, it turned out what had happened. In a place which, to the way of thinking of the people we are talking about, was quite far from that railway station, a very close member of the family had committed suicide in the same hour in which the figure had appeared to the little boy in the waiting room.|83/84|5f}} | |||

For the altar boy, the encounters with monks from the neighbourhood had also become the occasion for pressing questions: | |||

{{GZ|I often met the monks on my walks. I remember how much I would have liked to be addressed by them. They never did. And so I only ever carried away a vague but solemn impression of the encounter, which always stayed with me for a long time. It was in my ninth year that the idea took root in me: there must be important things in connection with the tasks of these monks that I had to get to know. Again, I was full of questions that I had to carry around with me unanswered.|28|22f}} | |||

After moving to Neudörfl, Rudolf Steiner first attended the local village school and then the secondary school in [[w:Wiener Neustadt|Wiener Neustadt]]. In his history lessons he studied [[w:Immanuel Kant|Kant]]'s ''[[w:Critique of Pure Reason|Critique of Pure Reason]] ({{German|''Kritik der reinen Vernunft''}}) at an early age: | |||

{{GZ|I now separated the individual sheets of the Kant booklet, stapled them into the history book I had in front of me during the lesson, and now read Kant while history was "taught" from the lectern. This was, of course, a great injustice to school discipline; but no one minded and it interfered so little with what was required of me that I got the mark of 'excellent' in history at that time.|28|43}} | |||

=== As a student in Vienna === | |||

Steiner studied biology, chemistry, physics and mathematics at the [[w:Vienna|Vienna]] [[w:TU Wien|College of Technology]] ({{German|''Technische Hochschule Wien''}}, now called [[w:TU Wien|TU Wien]]) from 1879. The student developed a high regard for the German professor [[Karl-Julius Schröer]]. On Schröer's recommendation, he edited Goethe's scientific writings in Kürschner's Deutscher Nationalliteratur {{GZ||28|124f}} and published literary essays in newspapers. From 1882 to 1887 Steiner's family lived in [[w:Brunn am Gebirge|Brunn am Gebirge]]. From 1884 to 1890 Steiner earned his living by working as a private tutor in a prominent Viennese family for a child with hydrocephalus who was considered unschoolable and who thus later studied medicine and became a doctor. He established a friendship with the poet [[Marie Eugenie delle Grazie]]. [[Marie Lang]] mediated a same with [[w:Rosa Mayreder|Rosa Mayreder]], but Rudolf Steiner also cultivated more intensive contact with people such as the herbalist [[Felix Koguzki]]. | |||

=== As a Goethe researcher in Weimar === | |||

[[File:Goethe-Schiller-Archiv Weimar.JPG|thumb|The [[WikipediaDE:Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv|Goethe and Schiller Archive]] in Weimar]] | |||

In 1890, at Schröer's suggestion, Steiner took over the editing of [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe|Goethe]]'s scientific writings at the [[WikipediaDE:Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv|Goethe and Schiller Archive]] in [[w:Weimar|Weimar]] for the large Weimar Goethe edition, the so-called "Sophien-Ausgabe". | |||

Steiner left the Technical University in Vienna without a degree, but completed his doctorate in [[w:Rostock|Rostock]] in 1891 with his dissertation "Die Grundfrage der Erkenntnistheorie mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Fichtes Wissenschaftslehre. Prolegomena zur Verständigung des philosophischen Bewußtseins mit sich selbst" ("The Basic Question of Epistemology with Special Reference to Fichte's Wissenschaftslehre. Prolegomena on the Understanding of Philosophical Consciousness with Itself") to the degree of Dr. phil. | |||

{{GZ|External facts only meant that I could not do it in Vienna. I had officially finished secondary school, not grammar school, and had acquired my grammar school education privately by giving private lessons. That ruled out doing a doctorate in Austria. I had grown into 'philosophy', but had an official course of education behind me which excluded me from everything into which the study of philosophy places a person.|28|214}} | |||

Weimar was Steiner's first major journey, but it also brought new contacts: A move to [[Anna Eunike]], whom he later married; friendship with [[Gabriele Reuter]]; a sometimes problematic collaboration with Nietzsche's sister, [[w:Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche|Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche]], in whose [[w:Nietzsche Archive|Nietzsche Archive]] in [[w:Naumburg|Naumburg]] he stood before the benighted philosopher; an encounter with [[w:Ernst Haeckel|Ernst Haeckel]]; the experience of [[w:Heinrich von Treitschke|Heinrich von Treitschke]] as an authority who, for external reasons, found it difficult to communicate; and above all, collaboration on the Weimar edition with [[w:Herman Grimm|Herman Grimm]]. | |||

In 1894 Steiner published the fundamental epistemological work "Die Philosophie der Freiheit – Seelische Beobachtungsresultate nach naturwissenschaftlicher Methode" ("The Philosophy of Freedom - Mental Observational Results According to the Scientific Method"). Regarding the basic Christian attitude of this writing, Steiner expressed himself, among other things, as follows: | |||

{{GZ|This "Philosophy of Freedom" is actually a moral view, which wants to be a guide to revive the dead thoughts as moral impulses, to bring them to resurrection. In this respect, inner Christianity is definitely in such a philosophy of freedom.|211|121}} | |||

{{GZ|Hence my very "philosophy of freedom" has been called the philosophy of individualism in the most extreme sense. It had to be, because on the other hand it is the most Christian of philosophies.|212|103f}} | |||

An attempt to become a professor in [[w:Jena|Jena]] failed. | |||

=== Berlin === | |||

Between 1898 and 1900 Steiner edited the ''Magazin für Litteratur'' (''Magazine for Lit(t)erature'') in [[w:Berlin|Berlin]] and taught at the Workers' Education School until 1904. In 1902, together with [[Marie von Sivers]], he took over the leadership of the newly founded German section of the [[Theosophical Society]]. In the same year Steiner summarised the content of a series of lectures in which he had described the "emergence of Christianity from the mystical view" {{GZ||8|7}}. In the work "Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?" ("Knowledge of the Higher Worlds And Its Attainment") he presented the paths to spiritual self-knowledge and self-transformation on a basis that seemed to him to be in keeping with the times {{GZ||10}}. In 1904, in his work "Theosophy" {{GZ||9}} and later in "Occult Science" {{GZ||13}}, he presented the ideal content of [[Anthroposophy]], among other things, through explanations of the essential [[members]] of [[man]], the colours of the [[aura]] and the [[world evolution|planetary states]] of the [[Earth]]. A rich lecturing activity developed from his tasks in the Theosophical Society. The transcripts of the lectures given at that time and of later similar presentations, most of which were not reviewed by their creator due to the enormous workload, constitute the majority of the volumes of [[Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works]], the number of which has risen to over 400 to date. | |||

In 1913 the German Section separated from the Theosophical Society because the Christian anthroposophical approach of Rudolf Steiner and Marie von Sivers had increasingly met with disapproval and in 1911 [[w:Annie Besant|Annie Besant]] and [[w:Charles Webster Leadbeater|Charles Webster Leadbeater]] had proclaimed the [[Hindu]] boy [[w:Jiddu Krishnamurti|Jiddu Krishnamurti]] as the reincarnation of [[Jesus]] and the future world leader. The [[Anthroposophical Society]] was founded, which was joined by many Theosophical groups abroad. | |||

=== Dornach and the Goetheanum === | |||

[[File:Rudolf Steiner 1919.jpg|thumb|Rudolf Steiner 1919]] | |||

In 1914 Steiner married his collaborator [[Marie von Sivers]] in [[Dornach]]. | |||

The [[Anthroposophical Society]] grew rapidly and in 1913 construction began of the [[first Goetheanum]] in Dornach as a theatre and administration building for their annual meetings. Designed by Steiner, it was largely built by volunteers who had specialist knowledge or simply the will to learn something new. In the field of sculpture, [[Edith Maryon]] was instrumental. In 1919, the world's first performance of [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe|Goethe]]'s entire [[Goethe's Faust|Faust]] took place here. In Dornach, where the thunder of cannons could be heard almost continuously, outstanding artists from sixteen partly hostile countries worked together during the war. The Goetheanum is intended as a "house of language" or a "house of the word". From here people who are really fully aware of their humanity are to work in collaboration with other spiritual institutions - communities, schools and universities - for a new taking seriously of the inner side of the human being. | |||

==== Anthroposophical architecture ==== | |||

On the Dornach hill, Steiner had not only designed the first Goetheanum as the headquarters of the anthroposophical movement, but after the fire he also indicated the foundations for the construction of the second Goetheanum. The [[Glass House]] still gives an impression of what the first Goetheanum looked like. [[Haus Duldeck]] also has a spiritual-scientific architectural style, which can still be found in many Waldorf schools today. {{LZ||{{G|286}}, {{G|289}}}} | |||

==== Eurythmy ==== | |||

{{Main|Eurythmy}} | |||

[[Eurythmy]], which makes [[music]] and [[speech]] visible through movement, already had precursors in the performance art of [[Edouard Schuré]]]'s dramas by [[Mieta Waller]] and [[Marie Steiner]]. Steiner developed it between 1913 and 1924 in response to a request from [[Lory Maier-Smits]]. | |||

=== Expanded public work === | |||

Through his esoteric teachings for Eliza von Moltke, Rudolf Steiner met her husband [[Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke]] even before the [[w:World War I|World War I]]. He was Chief of the [[w:German General Staff|German General Staff]] from 1906 to 14 September 1914 and had contacts with a good number of the most important German politicians during the war. With his support, Steiner tried, among other things, to gain the position of official advocate for [[w:Germany|Germany]] in the world, but this was not granted to him by the German leadership on the grounds that he was an [[w:Austrians|Austrian]]. | |||

Steiner wrote together with [[w:Alfred Kubin|Alfred Kubin]] and [[w:Else Lasker-Schüler|Else Lasker-Schüler]], among others, in the journal "Das Reich", founded by [[a:Alexander von Bernus|Alexander von Bernus]]. | |||

==== Social Threefolding ==== | |||

{{Main|Social threefolding}} | |||

After the World War, Steiner increasingly promoted the idea of a [[threefolding of the social organism]] to the public from 1919 onwards, which envisaged the principle of a free [[spiritual life]], equality in [[legal life]] and fraternity in [[economic life]] (→ [[The Key Points of the Social Question]]). He wrote an appeal to the German people and to the cultural world to advance the idea, which was signed by prominent artists such as [[w:Hermann Bahr|Hermann Bahr]], [[w:Hermann Hesse|Hermann Hesse]] and [[w:Bruno Walter|Bruno Walter]]. Due to increasing attacks, especially from the political right, Steiner had to stop his activities in this regard in [[w:Germany|Germany]] in 1922, after an assassination attempt on him was only just defeated. | |||

==== The Waldorf School ==== | |||

{{Main|Waldorf School}} | |||

In 1919 a first [[Waldorf School]] was founded in [[w:Stuttgart|Stuttgart]]. It had grown out of general education courses for workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory, which Steiner had organised, and had also received impetus from the endeavour to make the modern, branching work processes more manageable for the individual worker by means of a business education. The workers wanted the same for their children. In lecture series and teacher training courses, Steiner developed a new [[Waldorf education|art of education]] that was precisely attuned to the developmental stages and mental abilities and needs of the [[child]] on its way to becoming an adult human being. Parallel to the founding of the Waldorf School, Rudolf Steiner advised the establishment of a World School Association, which, however, was never implemented by those involved. The advice given for them was supplemented by a [[curative education course]]. | |||

==== The Burning of the First Goetheanum ==== | |||

[[File:Rudolf Steiner 1923.jpg|thumb|Rudolf Steiner 1923]] | |||

{{Main|Goetheanum}} | |||

On New Year's Eve 1922/23, opponents set fire to the [[Goetheanum]], destroying it to the ground (the insurance company also acknowledged arson as the cause). At the end of 1923 Steiner refounded the now "[[General Anthroposophical Society]]" at the [[Christmas Conference]]. In this way, unlike before, he wanted to bring the movement into one with its outer shell. The foundation stone for the larger successor building, the [[second Goetheanum]], was laid in 1924. | |||

==== Biodynamic agriculture ==== | |||

{{Main|Biodynamic agriculture}} | |||

In 1924 Steiner gave the starting signal for the development of [[biodynamic agriculture]] with an [[agriculture course]] in [[w:Koberwitz|Koberwitz]] near [[w:Breslau|Breslau]]. | |||

==== Anthroposophic medicine ==== | |||

{{Main|Anthroposophic medicine}} | |||

Also in the last period of his life, Steiner crowned his suggestions for an inwardly expanded medicine with the work "Grundlegendes für eine Erweiterung der Heilkunst nach geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen" (Basic Principles for an Expansion of the Art of Healing According to Spiritual Science), which he published together with the physician [[Ita Wegman]]. The approach here is that orthodox medicine is by no means rejected, but only supplemented by taking anthroposophical findings into account in treatment, adding certain methods and only partly, at the patient's request, also replacing certain therapies with anthroposophical ones of their own. | |||

==== The natural sciences ==== | |||

{{See also|Goetheanism}} | |||

Methodologically, the modern [[natural sciences]] strive to capture nature as quantitatively as possible and to represent it by means of a mathematical model, largely stripping away the directly experienceable [[sense qualities]]. However, according to Steiner, this only allows the laws of the dead, of the more or less mechanical, to be grasped. Contrary to the widespread opinion today, living things obey their own laws, which cannot be reduced to the quantitatively calculable. The Goethean natural sciences propagated by Rudolf Steiner accordingly strive for a purely qualitative explanation of the lawful interrelationships of natural [[phenomena]] given directly to the senses. More complex phenomena are either traced back to directly visible fundamental primordial phenomena or are transformed into one another through metamorphosis. Prime examples of this are [[Goethe's theory of colours]] and his study of [[metamorphosis]]. | |||

Those who study Steiner's statements that living things obey their own laws are opened to explore things that mediate between the living and the dead, building bridges from one to the other. This is possible in particular through the [[image-creating method]]s of [[anthroposophy]]. Thus, above all, [[Theodor Schwenk]] developed the [[drip image method]] for researching the quality of water and [[Ehrenfried Pfeiffer]] the method of [[copper chloride crystallisation]] for determining the quality of foodstuffs. | |||

==== Music ==== | |||

Steiner also made suggestions about music that changed the art of sound in a comprehensive way. He recommended formal changes to the instruments. He was able to win over the conductor [[w:Bruno Walter|Bruno Walter]] and the composer [[w:Viktor Ullmann|Viktor Ullmann]] for [[anthroposophy]]. | |||

==== The Christian Community ==== | |||

{{Main|Christian Community}} | |||

In 1920 Rudolf Steiner was asked by some theologians and theology students, at that time mainly [[w:Protestantism|Protestants]], in the circle around the Protestant pastor [[Friedrich Rittelmeyer]] (1872-1938) and [[Emil Bock]] (1895-1959) to give impulses for a renewal of religious life. Steiner then gave a series of lectures ([[GA 342]] - [[GA 346]]) on this subject between 1921 and 1924, giving detailed information on worship and formulating the texts to be used. In 1922, on this basis, the Christian Community was founded by 45 founding members as an independent Christian renewal movement completely separate from the [[Anthroposophical Society]]. | |||

{{GZ|What I have given to these personalities has nothing to do with the anthroposophical movement. I gave it to them as a private person, and I gave it in such a way that I emphasised with necessary firmness that the anthroposophical movement must have nothing to do with this movement for religious renewal; but that above all I am not the founder of this movement for religious renewal; that I count on this being made perfectly clear to the world, and that I have given the necessary advice to individual personalities who wanted to found this movement for religious renewal of their own accord, advice which was, however, suitable for the practice of a valid and spiritually vigorous cultus, spiritually filled with being, to be celebrated in a lawful manner with the forces from the spiritual world. I myself, in giving this advice, never performed any act of worship, but only showed those who wished to grow into this act of worship, step by step, how such an act of worship should be performed. That was necessary. And today it is also necessary that this should be correctly understood within the Anthroposophical Society.|219|169f}} | |||

== Spiritual Home and Future == | |||

As his contacts with artists of the very highest rank show (for example, Steiner gave systematic world-view guidance to [[w:Wassily Kandinsky|Wassily Kandinsky]], [[w:Christian Morgenstern|Christian Morgenstern]] and [[w:Joseph Beuys|Joseph Beuys]]), the founder of anthroposophy is at home in the whole of European culture. Here [[w:Thomas Aquinas|Thomas Aquinas]], through the emancipation of theological science from philosophy, is Steiner's most important forerunner. Rudolf Steiner, however, also developed his own literary style in his "[[Words of Truth]]" and "[[Mystery Dramas]]". After his death, [[w:Rosa Mayreder|Rosa Mayreder]] compared this with Goethe's realistic style in "[[w:Dichtung und Wahrheit|Dichtung und Wahrheit]]". | |||

Rudolf Steiner's work was discussed even during his lifetime. Controversial issues were many statements of anthroposophy, which was not accepted by representatives of university science, and the religious approaches, which were condemned by the official churches. After [[w:World War II|World War II]], especially in [[w:Germany|Germany]], Steiner's statements on the [[race]] question and [[Judaism]] were criticised. However, the works he wrote - as with many other philosophers - can partly only be understood from the context of the time. | |||

== Works == | |||

{{Main|Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works}} | |||

In addition to 24 books, Rudolf Steiner published a large number of writings and articles and gave more than 5600 lectures in Germany and abroad. A large number of the lectures have been preserved in transcripts by professional stenographers and lecture listeners. At first they were often published privately and in journals. Later, various publishing houses (including Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag, Rudolf-Steiner Verlag) began to edit and publish the lectures, books in the narrower sense and the accompanying wall charts. | |||

* [[GA 1|Einleitungen zu Goethes Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften]], 1884-1897 | |||

* [[GA 2|Grundlinien einer Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung, mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Schiller]], 1886 | |||

* [[GA 3|Wahrheit und Wissenschaft]], 1892 | |||

* [[GA 4|Die Philosophie der Freiheit]], 1894 | |||

* [[GA 5|Friedrich Nietsche, ein Kämpfer gegen seine Zeit]], 1895 | |||

* [[GA 6|Goethes Weltanschauung]], 1897 | |||

* [[GA 7|Die Mystik im Aufgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens und ihr Verhältnis zur modernen Weltanschauung]], 1901 | |||

* [[GA 18|Die Rätsel der Philosophie]], 1900 | |||

* [[GA 8|Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache]], 1902 | |||

* [[GA 9|Theosophie]], 1904 | |||

* [[GA 10|Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?]], 1904 | |||

* [[GA 11|Aus der Akasha-Chronik]], 1904-1908, als Buch 1939 | |||

* [[GA 12|Die Stufen der höheren Erkenntnis]], 1905-1908 | |||

* [[GA 13|Die Geheimwissenschaft im Umriss]], 1909 | |||

* [[GA 14|Vier Mysteriendramen]], 1910-1913 | |||

* [[GA 15|Die geistige Führung des Menschen und der Menschheit]], 1911 | |||

* [[GA 16|Ein Weg zur Selbsterkenntnis des Menschen. In acht Meditationen]], 1912 | |||

* [[GA 17|Die Schwelle der geistigen Welt. Aphoristische Ausführungen]], 1913 | |||

* [[GA 20|Vom Menschenrätsel]], 1916 | |||

* [[GA 21|Von Seelenrätseln]], 1917 | |||

* [[GA 22|Goethes Geistesart in ihrer Offenbarung durch seinen «Faust» und durch das Märchen von der Schlange und der Lilie]], 1918 | |||

* [[GA 23|Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage]], 1919 | |||

* [[GA 24|Aufsätze über die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus]], 1919 | |||

* [[GA 25|Drei Schritte der Anthroposophie: Philosophie, Kosmologie, Religion]], 1922 | |||

* [[GA 26|Anthroposophische Leitsätze]], 1924-1925 | |||

* [[GA 27|Grundlegendes für eine Erweiterung der Heilkunst nach geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen]], 1925 | |||

* [[GA 28|Mein Lebensgang]], 1924 | |||

== Literature == | == Literature == | ||

* [[Christoph Lindenberg]]: ''Rudolf Steiner - eine Biographie'', Verlag Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 978-3772515514 | * [[a:Christoph Lindenberg|Christoph Lindenberg]]: ''Rudolf Steiner - eine Biographie'', Verlag Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 978-3772515514 | ||

* [[Christoph Lindenberg]]: ''Rudolf Steiner - Eine Chronik: 1861-1925'', Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3772518614 | * [[a:Christoph Lindenberg|Christoph Lindenberg]]: ''Rudolf Steiner - Eine Chronik: 1861-1925'', Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3772518614 | ||

* [[Taja Gut]]: "Aller Geistesprozess ist ein Befreiungsprozess" - Der Mensch Rudolf Steiner, Pforte Verlag, 2000 | * [[a:Taja Gut|Taja Gut]]: "Aller Geistesprozess ist ein Befreiungsprozess" - Der Mensch Rudolf Steiner, Pforte Verlag, 2000 | ||

* [[Karen Swassjan]]: '' | * [[a:Karen Swassjan|Karen Swassjan]]: ''Rudolf Steiner: Ein Kommender'', Verlag am Goetheanum, Dornach 2005, ISBN 978-3723512593 | ||

* [[Mieke Mosmuller]]: ''Rudolf Steiner. Eine spirituelle Biographie'', Occident Verlag 2011, ISBN 978-3000362019 | * [[a:Mieke Mosmuller|Mieke Mosmuller]]: ''Rudolf Steiner. Eine spirituelle Biographie'', Occident Verlag 2011, ISBN 978-3000362019 | ||

* [[Peter Heusser]] (Hrsg.), Johannes Weinzirl (Hrsg.), [[Arthur Zajonc]] (Vorwort): '' | * [[a:Peter Heusser|Peter Heusser]] (Hrsg.), Johannes Weinzirl (Hrsg.), [[a:Arthur Zajonc|Arthur Zajonc]] (Vorwort): ''Rudolf Steiner: Seine Bedeutung für Wissenschaft und Leben heute'', Schattauer Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3794529476; eBook {{ASIN|B07N91XPKK}} | ||

* [[Peter Selg]]: ''Rudolf Steiner 1861 - 1925. Lebens- und Werkgeschichte. 3 Bände im Schuber'', Ita Wegman Institut 2012, ISBN 978-3905919271 | * [[a:Peter Selg|Peter Selg]]: ''Rudolf Steiner 1861 - 1925. Lebens- und Werkgeschichte. 3 Bände im Schuber'', Ita Wegman Institut 2012, ISBN 978-3905919271 | ||

* [[Martina Maria Sam]]: '' | * [[a:Martina Maria Sam|Martina Maria Sam]]: ''Rudolf Steiner: Kindheit und Jugend (1861–1884)'', Verlag am Goetheanum, Dornach 2018, ISBN 978-3723515914 | ||

* [[Lorenzo Ravagli]]: ''Rudolf Steiners Weg zu Christus: Von der philosophischen Gnosis zur mystischen Gotteserfahrung'', Akanthos Akademie Edition, Stuttgart 2018, ISBN 978-3746096971, eBook {{ASIN|B079YZH6CX}} | * [[a:Lorenzo Ravagli|Lorenzo Ravagli]]: ''Rudolf Steiners Weg zu Christus: Von der philosophischen Gnosis zur mystischen Gotteserfahrung'', Akanthos Akademie Edition, Stuttgart 2018, ISBN 978-3746096971, eBook {{ASIN|B079YZH6CX}} | ||

*[[Johannes Hemleben]]: Rudolf Steiner in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten, Rowohlts Monographien 79, 151.-160. Tausend, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1980 | *[[a:Johannes Hemleben|Johannes Hemleben]]: Rudolf Steiner in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten, Rowohlts Monographien 79, 151.-160. Tausend, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1980 | ||

*[[Gerhard Wehr]]: Rudolf Steiner. Leben - Erkenntnis - Kulturimpuls, Kösel Vlg, 1987 | *[[a:Gerhard Wehr|Gerhard Wehr]]: Rudolf Steiner. Leben - Erkenntnis - Kulturimpuls, Kösel Vlg, 1987 | ||

* [[Friedwart Husemann]]: ''Rudolf Steiners Entwicklung'', Vlg. am Goetheanum, Dornach 1999, ISBN 978-3723510476 | * [[a:Friedwart Husemann|Friedwart Husemann]]: ''Rudolf Steiners Entwicklung'', Vlg. am Goetheanum, Dornach 1999, ISBN 978-3723510476 | ||

* [[Friedwart Husemann]]: ''Rudolf Steiners Schriften in 50 kurzen Porträts'', Vlg. am Goetheanum, Dornach 2018, ISBN 978-3723515969 | * [[a:Friedwart Husemann|Friedwart Husemann]]: ''Rudolf Steiners Schriften in 50 kurzen Porträts'', Vlg. am Goetheanum, Dornach 2018, ISBN 978-3723515969 | ||

*[[Wolfgang Zumdick]]: ''Rudolf Steiner in Wien: Die Orte seines Wirkens'', Metroverlag 2010, ISBN 978-3993006020 | *[[a:Wolfgang Zumdick|Wolfgang Zumdick]]: ''Rudolf Steiner in Wien: Die Orte seines Wirkens'', Metroverlag 2010, ISBN 978-3993006020 | ||

* Ernst-Christian Demisch (Hrsg.), Christa Greshake-Ebding (Hrsg.), [[Johannes Kiersch]] (Hrsg.): ''Steiner neu lesen: Perspektiven für den Umgang mit Grundlagentexten der Waldorfpädagogik'' (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 12), Peter Lang GmbH 2014, ISBN 978-3631649695, eBook {{ASIN|B076FCC8PN}} | * Wolfgang G. Vögele (Hrsg.): ''Sie Mensch von einem Menschen! Rudolf Steiner in Anekdoten.'' Futurum 2012, ISBN 978-3856362379 | ||

* [[Michael Heinen-Anders]]: Aus anthroposophischen Zusammenhängen, BOD, Norderstedt 2010, S. 30 - 35; 48 - 49; 57 - 58. | * Ernst-Christian Demisch (Hrsg.), Christa Greshake-Ebding (Hrsg.), [[a:Johannes Kiersch|Johannes Kiersch]] (Hrsg.): ''Steiner neu lesen: Perspektiven für den Umgang mit Grundlagentexten der Waldorfpädagogik'' (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 12), Peter Lang GmbH 2014, ISBN 978-3631649695, eBook {{ASIN|B076FCC8PN}} | ||

* [[Michael Heinen-Anders]]: Aus anthroposophischen Zusammenhängen Band II, BOD, Norderstedt 2013 | * [[a:Michael Heinen-Anders|Michael Heinen-Anders]]: Aus anthroposophischen Zusammenhängen, BOD, Norderstedt 2010, S. 30 - 35; 48 - 49; 57 - 58. | ||

* [[Rudolf Steiner | * [[a:Michael Heinen-Anders|Michael Heinen-Anders]]: Aus anthroposophischen Zusammenhängen Band II, BOD, Norderstedt 2013 | ||

* | * Rudolf Steiner: ''Mein Lebensgang'', [[GA 28]] (2000), ISBN 3-7274-0280-6 {{Lectures|028}} | ||

* [[Rudolf Steiner]]: ''Wege zu einem neuen Baustil'', [[GA 286]] (1982) | * Rudolf Steiner: ''Gegenwärtiges und Vergangenes im Menschengeiste'', [[GA 167]] (1962), ISBN 3-7274-1670-X {{Lectures|167}} | ||

* | * Rudolf Steiner: ''Zeitgeschichtliche Betrachtungen. Das Karma der Unwahrhaftigkeit – Erster Teil'', [[GA 173]] (1978), ISBN 3-7274-1730-7 {{Lectures|173}} | ||

* | * Rudolf Steiner: ''Das Sonnenmysterium und das Mysterium von Tod und Auferstehung'', [[GA 211]] (1986), ISBN 3-7274-2110-X {{Lectures|211}} | ||

* | * Rudolf Steiner: ''Menschliches Seelenleben und Geistesstreben im Zusammenhange mit Welt- und Erdentwickelung'', [[GA 212]] (1998), ISBN 3-7274-2120-7 {{Lectures|212}} | ||

* Rudolf Steiner: ''Wege zu einem neuen Baustil'', [[GA 286]] (1982) {{Lectures|286}} | |||

* Rudolf Steiner: ''Eurythmie als sichtbarer Gesang'', [[GA 278]] (2001) {{Lectures|278}} | |||

* Rudolf Steiner: ''Eurythmie als sichtbare Sprache'', [[GA 279]] (1990) {{Lectures|279}} | |||

* Rudolf Steiner: ''Allgemeine Menschenkunde als Grundlage der Pädagogik'', [[GA 293]] (1992) {{Lectures|293}} | |||

;Criticism | ;Criticism | ||

Latest revision as of 22:24, 8 October 2022

Rudolf Steiner (born 25 or 27 February 1861 in Kraljevec, then Austrian Empire, now Donji Kraljevec in Croatia; † 30 March 1925 in Dornach near Basel), was an Austrian Goethe scholar, philosopher, and spiritual researcher. He opened a new, forward-looking scientific approach to the spiritual world through the anthroposophy he systematically developed as a science of the spiritual from 1900 onwards, based on the observation of thinking according to the scientific method, which he had already presented in detail in his Philosophy of Freedom published in 1894 and in the second part of which he founded an ethical individualism based on the self-aware free I of man, which must not be confused with his mere ego.

With eurythmy Steiner created a new art of movement and with the Goetheanum in Dornach as the seat of an independent School of Spiritual Science and through other buildings a new, organic architectural style. To a considerable extent he gave instruction in the art of recitation and declamation. The Waldorf school made possible more natural learning, biodynamic agriculture nourished life, the idea of the threefold social organism was to make possible the principle of freedom in spiritual life, equality in legal life and fraternity in economic life. Together with Ita Wegman, Steiner created anthroposophic medicine. He also gave suggestions to experts in other arts and the natural sciences, mostly at their request.

Life and work

Childhood

Rudolf Steiner's birthplace is Donji Kraljevec, a small village in northern Croatia not far from Čakovec. The village is located on the so-called Mur Island between the Mur and Drava rivers, which Rudolf Steiner also liked to call the "Two Rivers Land". His parental home was free-spirited, his father, Johann Steiner (1829-1910), was a railway official; to his mother Franziska Steiner, née Blie (1834-1918), he always remained in a loving and soulful relationship. Both parents came from the Lower Austrian Waldviertel, where they also returned after the father retired. Rudolf Steiner had two younger siblings: Leopoldine (1864-1927), who lived with her parents as a seamstress until their death, and Gustav (1866-1941), who was born deaf and was dependent on outside help throughout his life. His father had previously worked as a forester and hunter in the service of Count Hoyos of Horn (a son of Count Johann Ernst Hoyos-Sprinzenstein); when the latter refused to give him permission to marry in 1860, he resigned from the service and found employment as a railway telegraph operator on the southern railway. In «The Story of My Life» Steiner writes:

„My parents had their home in Lower Austria. My father was born in Geras, a very small town in the Lower Austrian Waldviertel, my mother in Horn, a town in the same area. My father spent his childhood and youth in close connection with the Premonstratensian monastery in Geras. He always looked back on this time of his life with great affection. He liked to tell how he had served in the monastery and how he had been taught by the monks. He was later a hunter in the service of the Count of Hoyos. This family had a property in Horn. That's where my father met my mother. He then left the hunting service and joined the Austrian Southern Railway as a telegraph operator. He was first employed at a small railway station in southern Styria. Then he was transferred to Kraljevec on the Hungarian-Croatian border. During this time he married my mother. Her maiden name is Blie. She comes from an old Horner family. I was born in Kraljevec on 27 February 1861. - That's how it came about that my place of birth is far removed from the region of the Earth from which I come.“ (Lit.:GA 28, p. 10)

The family moved several times: in 1862 to Mödling, a year later to Pottschach and in 1869 to Neudörfl. A deep mystery was presented to him by a railway carriage that caught fire:

„Once there was something quite "shocking" at the railway station. A railway train with freight was whizzing towards us. My father looked towards it. A rear wagon was on fire. The train crew had not noticed anything. The train came up to our station on fire. Everything that was happening made a deep impression on me. A fire had been started in one of the carriages by a highly inflammable substance. For a long time I wondered how such a thing could happen. What those around me told me about it was, as in similar matters, not satisfactory to me. I was full of questions and had to carry them around with me unanswered. So I became eight years old. - When I was eight, my family moved to Neudörfl, a small Hungarian village.“ (Lit.:GA 28, p. 20)

A supernatural experience from that time made a particularly deep impression on him:

„But the boy also had something else to look forward to. One day he was sitting all alone on a bench in the waiting room. In one corner was the stove, on a wall away from the stove was a door; in the corner from which one could see the door and the stove sat the boy. He was still very, very young at that time. And as he sat there, the door opened; he must have thought it natural that a personage, a woman's personage, should enter the door, whom he had never seen before, but who looked extraordinarily like a member of the family. The female personality entered the door, walked into the middle of the room, made gestures and also spoke words that can be rendered in the following manner: "Try to do as much as you can for me now and later!", she spoke to the boy. Then she was present for a while, making gestures that cannot disappear from the soul once one has seen them, went towards the oven and disappeared into it. The impression made on the boy by this event was very great. The boy had no one in his family to whom he could have spoken of such a thing, for the reason that he would have heard the harshest words about his stupid superstition if he had told anyone about this event. The following happened after this event. The father, who was otherwise a quite cheerful man, became quite sad after that day, and the boy could see that the father did not want to say something that he knew. After a few days had passed and another member of the family had been prepared in the appropriate way, it turned out what had happened. In a place which, to the way of thinking of the people we are talking about, was quite far from that railway station, a very close member of the family had committed suicide in the same hour in which the figure had appeared to the little boy in the waiting room.“ (Lit.: Contributions 83/84, p. 5f)

For the altar boy, the encounters with monks from the neighbourhood had also become the occasion for pressing questions:

„I often met the monks on my walks. I remember how much I would have liked to be addressed by them. They never did. And so I only ever carried away a vague but solemn impression of the encounter, which always stayed with me for a long time. It was in my ninth year that the idea took root in me: there must be important things in connection with the tasks of these monks that I had to get to know. Again, I was full of questions that I had to carry around with me unanswered.“ (Lit.:GA 28, p. 22f)

After moving to Neudörfl, Rudolf Steiner first attended the local village school and then the secondary school in Wiener Neustadt. In his history lessons he studied Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (German: Kritik der reinen Vernunft) at an early age:

„I now separated the individual sheets of the Kant booklet, stapled them into the history book I had in front of me during the lesson, and now read Kant while history was "taught" from the lectern. This was, of course, a great injustice to school discipline; but no one minded and it interfered so little with what was required of me that I got the mark of 'excellent' in history at that time.“ (Lit.:GA 28, p. 43)

As a student in Vienna

Steiner studied biology, chemistry, physics and mathematics at the Vienna College of Technology (German: Technische Hochschule Wien, now called TU Wien) from 1879. The student developed a high regard for the German professor Karl-Julius Schröer. On Schröer's recommendation, he edited Goethe's scientific writings in Kürschner's Deutscher Nationalliteratur (Lit.:GA 28, p. 124f) and published literary essays in newspapers. From 1882 to 1887 Steiner's family lived in Brunn am Gebirge. From 1884 to 1890 Steiner earned his living by working as a private tutor in a prominent Viennese family for a child with hydrocephalus who was considered unschoolable and who thus later studied medicine and became a doctor. He established a friendship with the poet Marie Eugenie delle Grazie. Marie Lang mediated a same with Rosa Mayreder, but Rudolf Steiner also cultivated more intensive contact with people such as the herbalist Felix Koguzki.

As a Goethe researcher in Weimar

In 1890, at Schröer's suggestion, Steiner took over the editing of Goethe's scientific writings at the Goethe and Schiller Archive in Weimar for the large Weimar Goethe edition, the so-called "Sophien-Ausgabe".

Steiner left the Technical University in Vienna without a degree, but completed his doctorate in Rostock in 1891 with his dissertation "Die Grundfrage der Erkenntnistheorie mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Fichtes Wissenschaftslehre. Prolegomena zur Verständigung des philosophischen Bewußtseins mit sich selbst" ("The Basic Question of Epistemology with Special Reference to Fichte's Wissenschaftslehre. Prolegomena on the Understanding of Philosophical Consciousness with Itself") to the degree of Dr. phil.

„External facts only meant that I could not do it in Vienna. I had officially finished secondary school, not grammar school, and had acquired my grammar school education privately by giving private lessons. That ruled out doing a doctorate in Austria. I had grown into 'philosophy', but had an official course of education behind me which excluded me from everything into which the study of philosophy places a person.“ (Lit.:GA 28, p. 214)

Weimar was Steiner's first major journey, but it also brought new contacts: A move to Anna Eunike, whom he later married; friendship with Gabriele Reuter; a sometimes problematic collaboration with Nietzsche's sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, in whose Nietzsche Archive in Naumburg he stood before the benighted philosopher; an encounter with Ernst Haeckel; the experience of Heinrich von Treitschke as an authority who, for external reasons, found it difficult to communicate; and above all, collaboration on the Weimar edition with Herman Grimm.

In 1894 Steiner published the fundamental epistemological work "Die Philosophie der Freiheit – Seelische Beobachtungsresultate nach naturwissenschaftlicher Methode" ("The Philosophy of Freedom - Mental Observational Results According to the Scientific Method"). Regarding the basic Christian attitude of this writing, Steiner expressed himself, among other things, as follows:

„This "Philosophy of Freedom" is actually a moral view, which wants to be a guide to revive the dead thoughts as moral impulses, to bring them to resurrection. In this respect, inner Christianity is definitely in such a philosophy of freedom.“ (Lit.:GA 211, p. 121)

„Hence my very "philosophy of freedom" has been called the philosophy of individualism in the most extreme sense. It had to be, because on the other hand it is the most Christian of philosophies.“ (Lit.:GA 212, p. 103f)

An attempt to become a professor in Jena failed.

Berlin

Between 1898 and 1900 Steiner edited the Magazin für Litteratur (Magazine for Lit(t)erature) in Berlin and taught at the Workers' Education School until 1904. In 1902, together with Marie von Sivers, he took over the leadership of the newly founded German section of the Theosophical Society. In the same year Steiner summarised the content of a series of lectures in which he had described the "emergence of Christianity from the mystical view" (Lit.:GA 8, p. 7). In the work "Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?" ("Knowledge of the Higher Worlds And Its Attainment") he presented the paths to spiritual self-knowledge and self-transformation on a basis that seemed to him to be in keeping with the times (Lit.:GA 10). In 1904, in his work "Theosophy" (Lit.:GA 9) and later in "Occult Science" (Lit.:GA 13), he presented the ideal content of Anthroposophy, among other things, through explanations of the essential members of man, the colours of the aura and the planetary states of the Earth. A rich lecturing activity developed from his tasks in the Theosophical Society. The transcripts of the lectures given at that time and of later similar presentations, most of which were not reviewed by their creator due to the enormous workload, constitute the majority of the volumes of Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works, the number of which has risen to over 400 to date.

In 1913 the German Section separated from the Theosophical Society because the Christian anthroposophical approach of Rudolf Steiner and Marie von Sivers had increasingly met with disapproval and in 1911 Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater had proclaimed the Hindu boy Jiddu Krishnamurti as the reincarnation of Jesus and the future world leader. The Anthroposophical Society was founded, which was joined by many Theosophical groups abroad.

Dornach and the Goetheanum

In 1914 Steiner married his collaborator Marie von Sivers in Dornach.

The Anthroposophical Society grew rapidly and in 1913 construction began of the first Goetheanum in Dornach as a theatre and administration building for their annual meetings. Designed by Steiner, it was largely built by volunteers who had specialist knowledge or simply the will to learn something new. In the field of sculpture, Edith Maryon was instrumental. In 1919, the world's first performance of Goethe's entire Faust took place here. In Dornach, where the thunder of cannons could be heard almost continuously, outstanding artists from sixteen partly hostile countries worked together during the war. The Goetheanum is intended as a "house of language" or a "house of the word". From here people who are really fully aware of their humanity are to work in collaboration with other spiritual institutions - communities, schools and universities - for a new taking seriously of the inner side of the human being.

Anthroposophical architecture

On the Dornach hill, Steiner had not only designed the first Goetheanum as the headquarters of the anthroposophical movement, but after the fire he also indicated the foundations for the construction of the second Goetheanum. The Glass House still gives an impression of what the first Goetheanum looked like. Haus Duldeck also has a spiritual-scientific architectural style, which can still be found in many Waldorf schools today. (Lit.: GA 286, GA 289)

Eurythmy

Eurythmy, which makes music and speech visible through movement, already had precursors in the performance art of Edouard Schuré]'s dramas by Mieta Waller and Marie Steiner. Steiner developed it between 1913 and 1924 in response to a request from Lory Maier-Smits.

Expanded public work

Through his esoteric teachings for Eliza von Moltke, Rudolf Steiner met her husband Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke even before the World War I. He was Chief of the German General Staff from 1906 to 14 September 1914 and had contacts with a good number of the most important German politicians during the war. With his support, Steiner tried, among other things, to gain the position of official advocate for Germany in the world, but this was not granted to him by the German leadership on the grounds that he was an Austrian.

Steiner wrote together with Alfred Kubin and Else Lasker-Schüler, among others, in the journal "Das Reich", founded by Alexander von Bernus.

Social Threefolding

After the World War, Steiner increasingly promoted the idea of a threefolding of the social organism to the public from 1919 onwards, which envisaged the principle of a free spiritual life, equality in legal life and fraternity in economic life (→ The Key Points of the Social Question). He wrote an appeal to the German people and to the cultural world to advance the idea, which was signed by prominent artists such as Hermann Bahr, Hermann Hesse and Bruno Walter. Due to increasing attacks, especially from the political right, Steiner had to stop his activities in this regard in Germany in 1922, after an assassination attempt on him was only just defeated.

The Waldorf School

In 1919 a first Waldorf School was founded in Stuttgart. It had grown out of general education courses for workers at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory, which Steiner had organised, and had also received impetus from the endeavour to make the modern, branching work processes more manageable for the individual worker by means of a business education. The workers wanted the same for their children. In lecture series and teacher training courses, Steiner developed a new art of education that was precisely attuned to the developmental stages and mental abilities and needs of the child on its way to becoming an adult human being. Parallel to the founding of the Waldorf School, Rudolf Steiner advised the establishment of a World School Association, which, however, was never implemented by those involved. The advice given for them was supplemented by a curative education course.

The Burning of the First Goetheanum

On New Year's Eve 1922/23, opponents set fire to the Goetheanum, destroying it to the ground (the insurance company also acknowledged arson as the cause). At the end of 1923 Steiner refounded the now "General Anthroposophical Society" at the Christmas Conference. In this way, unlike before, he wanted to bring the movement into one with its outer shell. The foundation stone for the larger successor building, the second Goetheanum, was laid in 1924.

Biodynamic agriculture

In 1924 Steiner gave the starting signal for the development of biodynamic agriculture with an agriculture course in Koberwitz near Breslau.

Anthroposophic medicine

Also in the last period of his life, Steiner crowned his suggestions for an inwardly expanded medicine with the work "Grundlegendes für eine Erweiterung der Heilkunst nach geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen" (Basic Principles for an Expansion of the Art of Healing According to Spiritual Science), which he published together with the physician Ita Wegman. The approach here is that orthodox medicine is by no means rejected, but only supplemented by taking anthroposophical findings into account in treatment, adding certain methods and only partly, at the patient's request, also replacing certain therapies with anthroposophical ones of their own.

The natural sciences

Methodologically, the modern natural sciences strive to capture nature as quantitatively as possible and to represent it by means of a mathematical model, largely stripping away the directly experienceable sense qualities. However, according to Steiner, this only allows the laws of the dead, of the more or less mechanical, to be grasped. Contrary to the widespread opinion today, living things obey their own laws, which cannot be reduced to the quantitatively calculable. The Goethean natural sciences propagated by Rudolf Steiner accordingly strive for a purely qualitative explanation of the lawful interrelationships of natural phenomena given directly to the senses. More complex phenomena are either traced back to directly visible fundamental primordial phenomena or are transformed into one another through metamorphosis. Prime examples of this are Goethe's theory of colours and his study of metamorphosis.

Those who study Steiner's statements that living things obey their own laws are opened to explore things that mediate between the living and the dead, building bridges from one to the other. This is possible in particular through the image-creating methods of anthroposophy. Thus, above all, Theodor Schwenk developed the drip image method for researching the quality of water and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer the method of copper chloride crystallisation for determining the quality of foodstuffs.

Music

Steiner also made suggestions about music that changed the art of sound in a comprehensive way. He recommended formal changes to the instruments. He was able to win over the conductor Bruno Walter and the composer Viktor Ullmann for anthroposophy.

The Christian Community

In 1920 Rudolf Steiner was asked by some theologians and theology students, at that time mainly Protestants, in the circle around the Protestant pastor Friedrich Rittelmeyer (1872-1938) and Emil Bock (1895-1959) to give impulses for a renewal of religious life. Steiner then gave a series of lectures (GA 342 - GA 346) on this subject between 1921 and 1924, giving detailed information on worship and formulating the texts to be used. In 1922, on this basis, the Christian Community was founded by 45 founding members as an independent Christian renewal movement completely separate from the Anthroposophical Society.

„What I have given to these personalities has nothing to do with the anthroposophical movement. I gave it to them as a private person, and I gave it in such a way that I emphasised with necessary firmness that the anthroposophical movement must have nothing to do with this movement for religious renewal; but that above all I am not the founder of this movement for religious renewal; that I count on this being made perfectly clear to the world, and that I have given the necessary advice to individual personalities who wanted to found this movement for religious renewal of their own accord, advice which was, however, suitable for the practice of a valid and spiritually vigorous cultus, spiritually filled with being, to be celebrated in a lawful manner with the forces from the spiritual world. I myself, in giving this advice, never performed any act of worship, but only showed those who wished to grow into this act of worship, step by step, how such an act of worship should be performed. That was necessary. And today it is also necessary that this should be correctly understood within the Anthroposophical Society.“ (Lit.:GA 219, p. 169f)

Spiritual Home and Future

As his contacts with artists of the very highest rank show (for example, Steiner gave systematic world-view guidance to Wassily Kandinsky, Christian Morgenstern and Joseph Beuys), the founder of anthroposophy is at home in the whole of European culture. Here Thomas Aquinas, through the emancipation of theological science from philosophy, is Steiner's most important forerunner. Rudolf Steiner, however, also developed his own literary style in his "Words of Truth" and "Mystery Dramas". After his death, Rosa Mayreder compared this with Goethe's realistic style in "Dichtung und Wahrheit".

Rudolf Steiner's work was discussed even during his lifetime. Controversial issues were many statements of anthroposophy, which was not accepted by representatives of university science, and the religious approaches, which were condemned by the official churches. After World War II, especially in Germany, Steiner's statements on the race question and Judaism were criticised. However, the works he wrote - as with many other philosophers - can partly only be understood from the context of the time.

Works

In addition to 24 books, Rudolf Steiner published a large number of writings and articles and gave more than 5600 lectures in Germany and abroad. A large number of the lectures have been preserved in transcripts by professional stenographers and lecture listeners. At first they were often published privately and in journals. Later, various publishing houses (including Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag, Rudolf-Steiner Verlag) began to edit and publish the lectures, books in the narrower sense and the accompanying wall charts.

- Einleitungen zu Goethes Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften, 1884-1897

- Grundlinien einer Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung, mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Schiller, 1886

- Wahrheit und Wissenschaft, 1892

- Die Philosophie der Freiheit, 1894

- Friedrich Nietsche, ein Kämpfer gegen seine Zeit, 1895

- Goethes Weltanschauung, 1897

- Die Mystik im Aufgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens und ihr Verhältnis zur modernen Weltanschauung, 1901

- Die Rätsel der Philosophie, 1900

- Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache, 1902

- Theosophie, 1904

- Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?, 1904

- Aus der Akasha-Chronik, 1904-1908, als Buch 1939

- Die Stufen der höheren Erkenntnis, 1905-1908

- Die Geheimwissenschaft im Umriss, 1909

- Vier Mysteriendramen, 1910-1913

- Die geistige Führung des Menschen und der Menschheit, 1911

- Ein Weg zur Selbsterkenntnis des Menschen. In acht Meditationen, 1912

- Die Schwelle der geistigen Welt. Aphoristische Ausführungen, 1913

- Vom Menschenrätsel, 1916

- Von Seelenrätseln, 1917

- Goethes Geistesart in ihrer Offenbarung durch seinen «Faust» und durch das Märchen von der Schlange und der Lilie, 1918

- Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage, 1919

- Aufsätze über die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus, 1919

- Drei Schritte der Anthroposophie: Philosophie, Kosmologie, Religion, 1922

- Anthroposophische Leitsätze, 1924-1925

- Grundlegendes für eine Erweiterung der Heilkunst nach geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen, 1925

- Mein Lebensgang, 1924

Literature

- Christoph Lindenberg: Rudolf Steiner - eine Biographie, Verlag Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 978-3772515514

- Christoph Lindenberg: Rudolf Steiner - Eine Chronik: 1861-1925, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3772518614

- Taja Gut: "Aller Geistesprozess ist ein Befreiungsprozess" - Der Mensch Rudolf Steiner, Pforte Verlag, 2000

- Karen Swassjan: Rudolf Steiner: Ein Kommender, Verlag am Goetheanum, Dornach 2005, ISBN 978-3723512593

- Mieke Mosmuller: Rudolf Steiner. Eine spirituelle Biographie, Occident Verlag 2011, ISBN 978-3000362019

- Peter Heusser (Hrsg.), Johannes Weinzirl (Hrsg.), Arthur Zajonc (Vorwort): Rudolf Steiner: Seine Bedeutung für Wissenschaft und Leben heute, Schattauer Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3794529476; eBook ASIN B07N91XPKK

- Peter Selg: Rudolf Steiner 1861 - 1925. Lebens- und Werkgeschichte. 3 Bände im Schuber, Ita Wegman Institut 2012, ISBN 978-3905919271

- Martina Maria Sam: Rudolf Steiner: Kindheit und Jugend (1861–1884), Verlag am Goetheanum, Dornach 2018, ISBN 978-3723515914

- Lorenzo Ravagli: Rudolf Steiners Weg zu Christus: Von der philosophischen Gnosis zur mystischen Gotteserfahrung, Akanthos Akademie Edition, Stuttgart 2018, ISBN 978-3746096971, eBook ASIN B079YZH6CX

- Johannes Hemleben: Rudolf Steiner in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten, Rowohlts Monographien 79, 151.-160. Tausend, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1980

- Gerhard Wehr: Rudolf Steiner. Leben - Erkenntnis - Kulturimpuls, Kösel Vlg, 1987

- Friedwart Husemann: Rudolf Steiners Entwicklung, Vlg. am Goetheanum, Dornach 1999, ISBN 978-3723510476

- Friedwart Husemann: Rudolf Steiners Schriften in 50 kurzen Porträts, Vlg. am Goetheanum, Dornach 2018, ISBN 978-3723515969

- Wolfgang Zumdick: Rudolf Steiner in Wien: Die Orte seines Wirkens, Metroverlag 2010, ISBN 978-3993006020

- Wolfgang G. Vögele (Hrsg.): Sie Mensch von einem Menschen! Rudolf Steiner in Anekdoten. Futurum 2012, ISBN 978-3856362379

- Ernst-Christian Demisch (Hrsg.), Christa Greshake-Ebding (Hrsg.), Johannes Kiersch (Hrsg.): Steiner neu lesen: Perspektiven für den Umgang mit Grundlagentexten der Waldorfpädagogik (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 12), Peter Lang GmbH 2014, ISBN 978-3631649695, eBook ASIN B076FCC8PN

- Michael Heinen-Anders: Aus anthroposophischen Zusammenhängen, BOD, Norderstedt 2010, S. 30 - 35; 48 - 49; 57 - 58.

- Michael Heinen-Anders: Aus anthroposophischen Zusammenhängen Band II, BOD, Norderstedt 2013

- Rudolf Steiner: Mein Lebensgang, GA 28 (2000), ISBN 3-7274-0280-6 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Gegenwärtiges und Vergangenes im Menschengeiste, GA 167 (1962), ISBN 3-7274-1670-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Zeitgeschichtliche Betrachtungen. Das Karma der Unwahrhaftigkeit – Erster Teil, GA 173 (1978), ISBN 3-7274-1730-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Das Sonnenmysterium und das Mysterium von Tod und Auferstehung, GA 211 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-2110-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Menschliches Seelenleben und Geistesstreben im Zusammenhange mit Welt- und Erdentwickelung, GA 212 (1998), ISBN 3-7274-2120-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Wege zu einem neuen Baustil, GA 286 (1982) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Eurythmie als sichtbarer Gesang, GA 278 (2001) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Eurythmie als sichtbare Sprache, GA 279 (1990) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Allgemeine Menschenkunde als Grundlage der Pädagogik, GA 293 (1992) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Criticism

- Heiner Ullrich: Rudolf Steiner: Leben und Lehre, Verlag C.H.Beck 2010, ISBN 978-3406612053; eBook ASIN: B004VLHGCY

- Miriam Gebhardt: Rudolf Steiner: Ein moderner Prophet, Pantheon Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3570551806

- Ulrich Kaiser: Der Erzähler Rudolf Steiner: Studien zur Hermeneutik der Anthroposophie, Info 3 2020, ISBN 978-3957791115; eBook ASIN B08VW9TSZC

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |