Imagination

Imagination, in the everyday sense, means the ability to create inner mental images that either recreate an external reality from memory or are the product of pure fantasy. Through spiritual training, imagining can be developed into a higher cognitive ability, which opens the view for higher levels of existence. Ideally, the body-bound sensual qualities are then completely stripped away. The imagination passes over into a purely soul-spiritual experience. Real imaginations resemble neither colourful sensory visionary images nor merely abstract imageless thoughts. Rather, they are in heightened form like the fine but very characteristic feelings that can be spontaneously provoked by sensual perceptions. Thereby, the feelings conveyed by the different senses often correlate with each other. In German this is called «Anmutung». Imagination, understood in this higher sense, is a psychic consciousness, also named etheric vision, in which the image consciousness of the Old Moon unites with the present object-consciousness on a higher level. That is why it is also called conscious image consciousness.

The concept of a "spiritual eye" in connection with the faculty of imagination goes back at least to Cicero, who speaks of the mentis oculi in his discussion of the appropriate use of the simile by the orator.[1] Cicero is clearly not referring to a real spiritual faculty of perception, such as is only given by the imagination, but to an inner sensual faculty of imagination that is as concrete as possible. He therefore recommends speakers to use vivid images and not those of which one has merely heard, "for the eyes of the mind are more easily directed to the objects which we have seen than to those which we have only heard".[2] In fact, external sensory perception, the inner sensory faculty of imagination and real imagination, which is a non-sensory, purely mental perception, make use of the same mental organ, namely the two-leaved brow chakra, albeit in different ways. When the activity of the two-petalled lotus located between the eyebrows turns inwards, the capacity for external, sensual perception arises. When its "astral tentacles" turn outwards, imagination arises (Lit.:GA 115, p. 54). This gives rise to a self-aware image-consciousness that man will fully develop on the New Jupiter, which will follow the present Earth evolution as the next embodiment of our planetary system. Imagination is a kind of fully conscious, non-dream clairvoyance. Imaginative consciousness begins to light up when the experiences of the astral body are depicted in the etheric body and are thrown back into consciousness through the latter in the form of moving images. True Imaginations are imaginary in the sense that they do not represent a sensory-physical reality, but are the purely mental image of an autonomous spiritual reality.

Bodiless consciousness

In order for the imagination to unfold, consciousness must detach itself from the bodily tool. Forces that are otherwise used up by the body must be turned into the soul:

„No human being knows how his movements, how everything that works there, that he can be an acting human being in the physical outer world, how that comes about and what force works there. Only the spiritual researcher notices this when he comes to so-called imaginative knowledge. There one first makes images which work by drawing stronger forces out of the soul than are otherwise used in ordinary life. Where then does this power come from which unleashes the images of imaginative experience in the soul? It comes from where the forces work that make us an acting human being in the world, that make us move our hands and feet. Because this is the case, one only comes to imagination when one can remain at rest, when one can bring the will of one's body to a standstill, can control it. Then one notices how this power, which otherwise moves the muscles, flows up into the soul-spirit and forms the imaginative images. So one accomplishes a rearrangement of the forces. Down there in the depths of the corporeal is something of our very own being, of which we feel nothing in ordinary life. By eliminating the physical, the spirit that is otherwise expressed in our actions penetrates up into the soul and fills it with what it would otherwise have to use for the physical. The spiritual researcher knows that he must remove from the body that which the body otherwise consumes. For imaginative knowledge, therefore, the bodily must be eliminated.“ (Lit.:GA 150, p. 92f)

Differences and similarities between sensual perception and imagination

In his "Outline of Occult Science" (Lit.:GA 13) Rudolf Steiner writes:

„The impressions which one receives of this world are in some respects still similar to those of the physical-sensuous. Whoever recognises imaginatively will be able to speak of the new higher world in such a way that he describes the impressions as sensations of warmth or cold, perceptions of sound or words, effects of light or colour. For he experiences them as such. But he is aware that these perceptions express something different in the imaginative world from what they do in the sensuous and real world. He recognises that behind them there are not physical-material causes, but spiritual-spiritual causes. If he has something like an impression of warmth, he does not attribute it to a piece of hot iron, for example, but he regards it as the outflow of a mental process such as he has hitherto known only in his inner mental life. He knows that behind imaginative perceptions there are spiritual things and processes, just as behind physical perceptions there are material-physical beings and facts. - In addition to this similarity between the imaginative and the physical world, however, there is a significant difference. There is something in the physical world that appears quite differently in the imaginative. In the physical world, we can observe a continual coming into being and passing away of things, an alternation of birth and death. In the imaginary world, this phenomenon is replaced by a continuous transformation of one into the other. For example, in the physical world one sees a plant perish. In the imaginative world, to the same extent that the plant withers away, the emergence of another form appears, which is physically imperceptible and into which the decaying plant gradually transforms itself. When the plant has disappeared, this structure is fully developed in its place. Birth and death are concepts that lose their meaning in the imaginative world. In their place comes the concept of the transformation of one into the other.- Because this is so, those truths about the nature of man become accessible to imaginative cognition which have been communicated in this book in the chapter "Nature of Humanity". For physical-sensual perception only the processes of the physical body are perceptible. They take place in the "area of birth and death". The other members of human nature: the life body, the sentient body and the I, are subject to the law of transformation, and their perception is opened up to imaginative cognition. He who has advanced to this realisation perceives how that which lives on with death in a different mode of existence dissolves, as it were, out of the physical body.“ (Lit.:GA 13, p. 350f)

„That is the peculiarity of the anthroposophical method, that it takes sense perception as its very model. Other nebulous mystics can be found who say: sense perception - something very inferior! One must leave them. One must put oneself into the dreamlike, into the mystical, into the sense-absent! - This, of course, only leads to a half-sleep, not to real meditation. Anthroposophy follows the opposite path: it takes sensory perception as a model in terms of its quality, intensity and liveliness. So that in this meditation the human being moves as freely as he otherwise moves in sense perception. He is not at all afraid that he will become a dry sober person. The things which he experiences in this way in all objectivity already keep him from dry philistrosity, and he has no need to rise into dreamlike nebulosity because of the objects which he experiences, for the sake of overcoming everydayness.

Thus, by meditating correctly, a person achieves freedom of movement in thought. In this way, however, the thoughts themselves are freed from their previous abstract character, they become pictorial. And this now occurs in full waking consciousness, in the midst of other healthy thinking. For one must not lose this. The hallucinist, the rapturous one, in the moment when he hallucinates, raves, is entirely hallucinant, entirely rapturous, he completely puts away common sense; he who follows the methods described here must not do that. He always has common sense beside him. He takes it with him through all that which he experiences in the pictorial life of thought. And what happens as a result? Yes, you see: in the fully awake state, that occurs which otherwise only forms the unconscious life in the imagery of the dream. But this is precisely the difference between the imagination and the dream: in the dream everything is made within us; then it penetrates from unrecognised depths into waking life, and we can only observe it afterwards. In imagination, in the preparation for imagination, in the meditative content, we do ourselves what is otherwise done in us. We set ourselves up as creators of images that are not mere fantasy images, but differ from fantasy images in intensity, in liveliness, just as dream images differ from mere fantasy images. But we do it all ourselves, and that is what matters. And by doing it ourselves we are also freed from a thorough illusion, which consists in the fact that one could regard what one does in this way as a manifestation from the objective outer world. We never do, for we are conscious that we make this whole fabric of images ourselves. The hallucinant thinks his hallucinations are reality. He takes images for reality because he does not make them himself, because he knows that they are made. This creates the illusion for him that they are reality. He who prepares himself by meditation for the imagination cannot come into the case of thinking that what he forms there himself is real. A first step towards supersensible knowledge will consist precisely in becoming free from illusion by forming the whole fabric, which we now regard as the inner ability to call forth images of such vividness as dream-images otherwise are, in completely free will. And of course one would have to be crazy now if one thought that was reality!

Now, the next stage in this meditating consists in acquiring again the ability to let these images, which have something fascinating about them, and which, if the human being does not develop them in complete freedom as in meditating, actually take hold like parasites, that one can again let these images disappear completely from the consciousness, that one also obtains the inner volition to let these images, if one wishes, again disappear completely. This second stage is as necessary as the first. Just as in life forgetting is necessary in comparison with remembering - otherwise we would always go about with the whole sum of our memories - so in this first stage of cognition the throwing away of the imaginative images is as necessary as the weaving, the shaping of these imaginative images.

But by having gone through all this, by having practised it, one has accomplished something with the soul which one might compare with the constant use of a muscle, the constant practising of it, which makes it strong. We have now accomplished an exercise in the soul by learning to weave images, to form images, and to suppress them again, and that all this is completely within the sphere of our free will. You see, through the training of the imagination, one has come to the conscious ability to form images, such as are otherwise formed in the unconscious life of dreams, over there in the world which one does not otherwise survey with one's ordinary consciousness, which are relegated to the states between falling asleep and waking up. Now one consciously unfolds this same activity. So in meditation, which aims at imaginative cognition, one develops the will to attain the ability to consciously create images, and again the ability to consciously remove images from the consciousness. Through this comes another ability.

This ability is one that is otherwise involuntarily present not during sleep, but at the moment of waking and falling asleep. The moment of waking up and falling asleep can take the form of taking over what one has experienced from falling asleep to waking up in the dream remnants, then judging from there what is over there. But what we open ourselves to when we wake up can also surprise us in such a way that all memory of the dream sinks in. In general, we can say that in dreams something chaotic, something like an erratic structure, projects into waking life from outside the ordinary waking life. It enters through the fact that during sleep man develops the pictorial activity of creating imaginations. If, in waking life, he develops the activity of creating imaginations and the activity of removing imaginations, he can come out of his preparation for imagination into a state devoid of consciousness: then it is like waking up, and from beyond the carpet of the senses - what I have now marked here in the drawing with a red circle - those entities penetrate us through the carpet of the senses on the pathways of thought developed through meditation, which are beyond this carpet of the senses. We penetrate the carpet of the senses when we remain with empty consciousness after the images we have made; then the images come in through inspiration from beyond the world of the senses. We enter that world which lies beyond the world of the senses. We prepare ourselves for inspiration through the imaginative life. And inspiration consists in our being able to consciously experience something like the moment of waking up, which is otherwise unconscious. Just as at the moment of waking something comes into our waking soul-life from beyond the waking soul-life, so then, when we have formed our soul-life through imagination in the way I have described, something comes in from beyond the consciousness of the sensory carpet.“ (Lit.:GA 303, p. 77ff)

Thinking and non-thinking visionary clairvoyants

„What gives revelations, real facts about the spiritual world, can enter the human soul in the most manifold ways. Certainly it is possible, and in numerous cases it is really so today, for people to come to visionary seeing without being keen thinkers - many more people come to clairvoyance who are not keen thinkers than are keen thinkers - but there is a great difference between the experiences in the spiritual world of those who are keen thinkers and those who are not. It is a difference that I can express in this way: What reveals itself from the higher worlds imprints itself best of all on those forms of imagination which we bring as thoughts to these higher worlds; that is the best vessel.

If we are not thinkers, then the revelations must seek other forms, for example, the form of the image, the form of the symbol. That is the most common way in which he who is a non-thinker receives the revelations. And you can then hear from those who are visionary clairvoyants, without being thinkers at the same time, how revelations are told by them in allegories. These are quite beautiful, but we must at the same time be aware that the subjective experience is different whether you have revelations as a thinker or as a non-thinker. If you have revelations as a non-thinker, the symbol is there; there is this or that figure. That reveals itself from the spiritual world. Let us say you see an angelic figure, this or that symbol that expresses this or that, for my sake a cross, a monstrance, a chalice - that is there in the supersensible field, you see it as a finished picture. You are clear: this is not reality, but it is an image.

Experiences from the spiritual world are experienced in a somewhat different way for the subjective consciousness of the thinker, not quite in the same way as for the non-thinker. There they are not, as it were, given all at once, as if shot out of a pistol; there you have them before you in a different way. Take, I will say, a non-thinking visionary clairvoyant and a thinking one. The non-thinking visionary clairvoyant and the thinking visionary clairvoyant would both receive the same experiences. Let us put a particular case: The non-thinking visionary clairvoyant sees this or that phenomenon of the spiritual world, the thinking visionary clairvoyant does not see it yet, but a little later, and at the moment when he sees it, it has already been grasped by his thinking. He can already distinguish it, he can already know whether it is truth or falsehood. He sees it a little later. But when he sees it a little later, the appearance from the spiritual world confronts him in such a way that he has penetrated it mentally and can distinguish whether it is deception or reality, so that he has something earlier, so to speak, before he sees it. Of course, he has it at the same moment as the non-thinking visionary clairvoyant, but he sees it a little later. But then, when he sees it, the appearance is already interspersed with the judgement, with the thought, and he can know exactly whether it is an illusion, whether his own wishes are objectified there, or whether it is objective reality. That is the difference in subjective experience. The non-thinking visionary clairvoyant sees the apparition immediately, the thinking one somewhat later. But for the former it will remain as he sees it, he can describe it in this way. The thinker, however, will be able to place it entirely in the context of what is then in the ordinary physical world. He will be able to relate them to this world. The physical world, like that appearance, is also a revelation from the spiritual world.“ (Lit.:GA 117, p. 81f)

Imagination, hallucination, illusion, vision and fantasy

Imaginations must be clearly distinguished from hallucinations, visions and fantasies or merely arbitrary ideas.

A hallucination (Latin: (h)alūcinātio "thoughtless talk, daydreaming"; from Greek: ἀλύειν halýein "to be out of one's mind" and γένεσις genesis "birth, origin, generation") is a perception of a sense area without a stimulus basis. This means, for example, that non-existent objects are seen, or voices are heard without anyone speaking. Hallucinations can affect all sensory areas. In an illusion, on the other hand, a real object is perceived in a different way: An actually existing fixed object appears to move or faces appear to be recognisable in irregular patterns.

„I would just like to indicate a radical difference between the visionary, the hallucinatory and what the spiritual researcher sees. Why is it that so many people believe they are already in the spiritual world when they only have hallucinations and visions? Yes, people are so reluctant to get to know something really new! They like to hold on to the old, in which they are already inside. Basically, in hallucinations and visions, the morbid soul-forms confront us in the same way as the outer sensual reality confronts us. They are there; they present themselves before us. To a certain extent, we do nothing when they present themselves before us. The spiritual researcher is not in this position in relation to his new spiritual element. I have spoken of the fact that the spiritual researcher must concentrate and work up all the powers of his soul which lie dormant in ordinary life. But this requires him to use a spiritual energy, a spiritual strength, which is not present in outer life. But he must always hold on to this strength when he enters the spiritual world. Man remains passive, he need not exert himself: that is the characteristic of hallucinations, of visions. The moment we become passive towards the spiritual world, even for a moment, everything immediately disappears. We must be constantly active, actively present. That is why we cannot deceive ourselves, because nothing can appear before our eyes from the spiritual world in the same way as a vision or hallucination appears before our eyes. We must be present everywhere with our activity, with every atom of that which confronts us from the spiritual world. We must know what it is like. This activity, this continuous activity, is necessary for real spiritual research. But then we enter a world that is radically different from the physical-sensual world. One enters a world where spiritual beings, spiritual facts are around us.“ (Lit.:GA 155, p. 224f)

„When this inner experience, this inner experience has come, when one really feels that you need not now merely stand still with the sense world, you experience something through your imaginative thinking, through your living thinking, when you pierce the carpet of the senses, when you try to look into your inner being, you experience something that ordinary natural science cannot experience, that ordinary mysticism can only bring before the soul in an illusionary way, if you honestly experience this as a result of an inner development, then you can be sure that you are on a path that can now really lead to higher worlds.

At first one has nothing external before one. One has only strengthened the old forces, made them more intense. But one soon notices that something essential, something important is happening in the consciousness of the human being. You gradually get something like an introspection that extends over the whole of your life since birth. Yes, this is the first supersensible reality that one experiences: one's own inner life since birth in a clear tableau. And this clear tableau expresses itself in the fact that one's thinking is in a different relationship to what one now perceives outwardly than one used to be with one's thinking to what was given outwardly and experienced inwardly.

In ordinary life one develops thinking. One thinks about something. The thoughts are in the soul, they are subjective. The other is objective, the other is outside. One feels one's thought activity separate from that which is outside. Now you have the tableau of your own soul life before you since birth. But I would like to say that the thoughts go into this fabric. One feels oneself inside this tissue. One says to oneself: now you are really beginning to grasp yourself. You have to give up your thoughts to that which objectively comes before your consciousness. - This even gives rise to a certain, I would say, painful experience at first for the anthroposophical spiritual researcher. The anthroposophical spiritual researcher must go through such painful experiences with his experiences in various directions. He must not be afraid to go through inwardly difficult, often painful things in a certain way. I will also have to speak about this today in another direction. But now, in relation to this tableau of life, one experiences first of all that one feels one's own being in a kind of inner oppression. One does not feel it with the ease with which one usually cherishes thoughts and ideas, with which feelings, impulses of will, desires and the like are usually in us, one feels it like something that oppresses one. In short, one feels reality in this oppression. If one does not have this oppression, then one only has a thought-formation, then one does not have reality. But by carrying into this oppression everything that one used to have in the way of freely unfolding thought tissues, one is thereby protected from developing something like illusions, visions, hallucinations with one's imaginative knowledge.

This is something that is so often thrown in the way of anthroposophical spiritual science. They say: With its exercises nothing else develops but vision, hallucination. It brings to the surface of consciousness, as it were, suppressed nervous forces, and no one can prove the reality of what anthroposophical spiritual science speaks of as higher worlds. Whoever pays attention to what I have already said today will feel that the path taken by anthroposophical spiritual science is the opposite of all those paths which lead to visions, hallucinations or even to mediumism. Everything that leads to mediumism, to hallucinations, to visions, ultimately emerges only from the organs of the body that have become diseased and which, as it were, exhale their spiritual-soul in a pathological way up into consciousness. All this lies beneath the senses. On the other hand, that which is formed as imaginative cognition lies above ordinary sense perception, is formed precisely on objectivity, not on the morbid interior.“ (Lit.:GA 79, p. 19ff)

The vision (from Latin: videre "to see"; French: vision "dream") is an imaginatively perceived spiritual appearance in the astral world, which is unconsciously carried over into the sensual daytime consciousness. Visions are not only limited to impressions that are remotely comparable to sensual sight, but other sensual qualities, e.g. smelling, tasting, etc., can also play a role, insofar as the sensual qualities have their origin in the astral world. An exclusively heard event is also called an audition (Latin: audire "to hear").

„Visions arise from the fact that man unconsciously carries over experiences of sleep into day-life, and that day-life shapes these sleep-experiences into conceptions which are then inwardly much more saturated, much more full of content than the ordinary conceptions which are shadowy; by carrying over such conceptions man makes them into such vivid, colourful conceptions.“ (Lit.:GA 227, p. 163)

The vision is a retarded remnant of the old clairvoyance. It occurs when the consciousness, which today is normally centred in the I, dives down into the astral body, although it is distorted by the experiences of the object consciousness.

„Whoever dives down there after having been a present human being, everything that is below is coloured here with the experiences from above. One brings into this subconsciousness, like a shell, what one has experienced above, and thereby does not get a pure conception, an unclouded picture, but a picture clouded by the experiences of the object-consciousness.“ (Lit.:GA 57, p. 408f)

Imagination also do not appear as abstract concepts. They are richer, more vivid, more pictorial. In a way, they can be compared to ideas of memory. Just as the latter refer to past sensual events, spiritual events are expressed in the imagination.

„This imaginative cognition does not live in the abstract concepts to which we are accustomed in ordinary logical thinking, but neither should we think that this cognition is something perhaps merely fantastic. If we want to characterise what is present more externally, we must think of that form of experience which the human being has when he brings out ideas of memory from the subsoil of his organisation, or also when these ideas of memory, stimulated by this or that, emerge from this subsoil as if of their own accord. If, then, we take into the soul's eye that which is a memory-imagination, we shall have given the way in which imaginations also live in the soul. They live with the same intensity, indeed with an often far greater intensity than the ideas of memory. But just as the ideas of memory show by their own appearance, by their own content, what the experience was which the human being had perhaps years ago and of which they are an image, so these imaginations, by being called into the soul, show that they are not at first connected with a personal experience, but that they refer, although they appear precisely with the character of memory imaginings, to a world which is not sensuous but nevertheless quite objective, which lives and weaves within the world of the senses, but does not reveal itself through the organs of perception of the senses.

Thus one could first characterise in a positive sense the more external nature of the cognitive imaginings. In a negative sense, one must say what these cognitive imaginings are not. They are not somehow something similar to a vision, a hallucination or the like. On the contrary, they lead man's soul condition in the opposite direction from that in which it moves when it falls into visions, hallucinations and the like. Imaginations of cognition are healthy soul-experiences in the same sense in which visions, hallucinations and so on are sick soul-experiences.“ (Lit.:GA 78, p. 89f)

„If, by concentrating the life of thought, feeling and sensation, one is able to strengthen the life of the soul in such a way that one can enter into this seeing consciousness, then one is first of all enabled to refrain from everything that otherwise confronts the everyday observation of the human being in sensual perception. One has moved beyond this sensual perception. One lives in another inner soul being, lives first in what one can call imaginative consciousness. I call it imaginative consciousness, not because something unreal is to be represented, but because the soul in this consciousness is filled with images, and at first with nothing but images, but with images of a reality. And furthermore, that the soul is filled with such images, of which it sees quite clearly that they are not themselves a reality, but images of a reality, the soul still knows that it stands within the real world context, that it does not weave these images out of some nothingness out of arbitrary ideas, but out of an inner necessity. This comes from the fact that the soul has placed itself in the real world context and does not create out of this in its image-creation in the way that mere fantasy does, but that what images are woven retains the character of reality.

It is of special importance that this first stage of spiritual experience be carefully observed, for there are two directions in which error can occur. One is that one may confuse what is meant here as the imaginative world with those images which rise from the morbid, abnormal consciousness, with all kinds of visionary things or the like. But you will have seen from what has already been developed here how, in the work of the spiritual researcher, all the precautions are taken towards the way of entering the spiritual world which strictly repel the indefinite swimming and floating in all kinds of visionary things. The vision enters the soul in such a way that one does not feel involved in its occurrence. It appears as an image, but one cannot participate in the formation of the image; one is not inside the formation of the image. Therefore one does not know the origin. The visionary image always comes merely from the organism, and what steams out of the organism is not soul-spiritual, it is a veiling perhaps of a spiritual-soul. What is at issue is to distinguish precisely the whole unconscious life in all kinds of visions from what the spiritual researcher means by imaginative conscious life. This consists in being present in all the images that are woven, as one is only somehow present in the fully conscious thinking that goes from thought to thought.

There is no other way of penetrating the spiritual world than if the activity through which one enters is as fully conscious as the most conscious thought-life. The only difference is that thoughts as such are shadowy, faded, and that they are acquired from external things or somehow rise from memory, while that which is meant here as imagination is woven by the soul itself at the moment when it occurs.

It is only to be noted that, on the other hand, this imagination must not be confused with what is rightly called fantasy. What the human fantasy weaves is also woven up from the subconscious; this is, however, often bound to the inner laws of real life, especially when the fantasy works as Goethe's does. But man does not stand in what he weaves in the imagination in such a way that he is conscious of his weaving. In the construction of the imaginative picture he is left to an inner real necessity. In the imaginative experience, however, he does not weave as he does in fantasy, but in such a way that he abandons himself to an objective necessity of the world. It is quite necessary to know that that on the basis of which the spiritual researcher must first work, which appears as an objective fact in his consciousness, is neither visionary nor fantasy, but that it must be absolutely distinguished from these two - I would like to say polar - opposites as something standing in the middle. In standing in the imaginative life, one is indeed in a similar position as one stands with one's sensual human being before a mirror. One knows that he who stands there is standing in a reality, he is a reality which feels itself to be of flesh and blood, but nothing of this reality passes over into the mirror. In the mirror there is only an image; but this image is a likeness, and one knows it in its relation to reality.“ (Lit.:GA 67, p. 328ff)

It should be noted that the imaginative "seen" is absolutely invisible, the "heard" completely inaudible, since it is precisely not a sensual, but a purely supersensual perception actively and consciously produced by one's own spiritual activity, but completely determined by itself in terms of content. But since in the earthly embodied human being the activity of the body and in particular the sphere of the senses still quietly resonates, it is nevertheless quite natural and appropriate to describe the imaginative experience in sensual terms. However, one must not confuse the description in sensual terms or the illustration through corresponding drawings with what is actually imaginatively "seen":

„One will now find that those people who can make supersensible observations describe what they see in such a way that they make use of expressions borrowed from sensual perceptions. Thus the elementary body of a being of the sensuous world, or a purely elementary being, may be described in such a way that it is said to reveal itself as a self-contained, variously coloured body of light. It flashes in colours, glows or shines and lets us notice that this appearance of colour or light is its expression of life. What the observer is actually talking about is quite invisible, and he is conscious of the fact that the image of light or colour has nothing more to do with what he perceives than, say, the writing in which a fact is communicated has to do with that fact itself. Nevertheless, one has not merely expressed a supersensible in an arbitrary way through sensory perceptions; but during the observation one has really had the experience which is similar to a sense impression. This comes from the fact that in supersensible experience the liberation from the sensuous body is not complete. The latter still lives with the elementary body and brings the supersensible experience into a sensuous form. The description thus given of an elementary entity is then actually such that it appears like a visionary or fantastic compilation of sensory impressions. If the description is given in this way, it is nevertheless the true reproduction of what has been experienced. For one has seen what one describes. The mistake that can be made does not lie in the fact that one describes the picture as such. It is only a mistake if one takes the picture for reality and not what the picture points to as the reality corresponding to it.

A person who has never perceived colours - a person born blind - will not, if he acquires the corresponding ability, describe elementary entities in such a way that he says they flash up as colour phenomena. He will make use of those ideas of sensation for expression which are accustomed to him. For people who can see sensually, however, a description is quite suitable which uses the expression, for instance, that a coloured figure is flashing. In this way they can form the sensation of what the observer of the elementary world has seen. And this does not only apply to communications which a clairvoyant - let it be so called a man who can observe through his elementary body - makes to a non-clairvoyant, but also to the communication of clairvoyants among themselves. In the world of the senses man lives in his sensuous body, and this clothes his super-sensible observations in sensuous forms; therefore, within human life on earth, the expression of super-sensible observations through the sensuous images they produce is, after all, at first a useful way of communication.

What matters is that he who receives such a communication has an experience in his soul which stands in the right relation to the fact in question. The sensuous images are only communicated so that something may be experienced through them. As they present themselves, they cannot occur in the world of the senses. That is their peculiarity. And that is why they also evoke experiences that do not relate to anything sensuous.“ (Lit.:GA 16, p. 32ff)

Supersensory experiences can occur spontaneously at first. A higher ability consists in bringing them about quite consciously out of the ordinary life of the soul.

„The supersensory experiences can occur in such a way that they appear at certain times. They then overtake the human being. And he then has the opportunity to learn something about the supersensible world through his own experience, to the extent that he is, so to speak, more or less often graced by it by the fact that it shines into his ordinary soul life. A higher ability, however, consists in arbitrarily bringing about clairvoyant observation out of the ordinary life of the soul. The way to attain this ability is generally through an energetic continuation of the inner strengthening of the soul-life. But much also depends on the attainment of a certain mood of the soul. A calm, serene behaviour towards the supersensible world is necessary. A behaviour which is just as far removed from the burning desire to experience as much and as clearly as possible, as it is from personal disinterest in this world. The burning desire acts in such a way that it spreads something like an invisible mist before the bodiless seeing. The lack of interest is such that supersensible things really reveal themselves, but are simply not noticed. This lack of interest is sometimes expressed in a very special form. There are people who would like to have experiences of clairvoyance in the most honest way. But from the outset they have a very definite idea of what they must be like if they are to recognise them as genuine. And then real experiences come; but these flit by without any interest being shown in them, because they are just not as one has imagined they should be.“ (Lit.:GA 16, p. 34f)

„In my "Theosophy" you will find that the spiritual is seen in the form of a kind of aura. It is described in colours. Coarse-minded people who do not go into things further, but write books themselves, believe that the seer describes the aura, describes it by having the opinion that there is really such a mist before him. What the seer has before him is a spiritual experience. When he says that the aura is blue, he is saying that he has a spiritual experience which is as if he were seeing blue. He describes in general everything that he experiences in the spiritual world and which is analogous to what can be experienced in the sensuous world in terms of colours.“ (Lit.:GA 271, p. 185)

Translation of imaginations into sensual images

It is clear from the above that the supersensually experienced imaginations must not be confused with visionary sensually seen images. Using the example of the first apocalyptic seal, Rudolf Steiner shows that it is nevertheless useful to translate imaginations into sensuous images.

„The first seal represents man's whole earthly development in the most general way. In the "Revelation of St. John" it is indicated by the words: "And when I turned, I saw seven golden candlesticks, and in the midst of the seven candlesticks one like unto the Son of man, clothed in a long robe, and girded about the breast with a golden girdle. And his head and his hair were white as white wool, as the snow; and his eyes were as a flame of fire; and his feet were as brass burning in the furnace; and his voice was as the sound of great waters; and he had in his right hand seven stars; and out of his mouth proceeded a sharp two-edged sword; and his face shone as the bright sun." In general terms, such words point to the most comprehensive secrets of the development of mankind. If one wanted to describe in detail what each of these deeply significant words contains, one would have to write a thick volume. Our seal is a pictorial representation of this. Among the bodily organs and forms of expression of man there are those which in their present form represent the descending stages of development of earlier forms, which have therefore already passed their degree of perfection; others, however, represent the initial stages of development; they are now, as it were, the preparations for what they are to become in the future. The secret scientist must know these secrets of development. The organ of speech represents an organ which in the future will be something much higher and more perfect than it is at present. By expressing this, one touches upon a great mystery of existence, which is often also called the "mystery of the creating word". This is an indication of the future state of this human organ of speech, which will one day, when man is spiritualised, become a spiritual organ of production (procreation). In myths and religions, this spiritual production is indicated by the appropriate image of the "sword" coming out of the mouth. Thus every line, every point in the picture signifies something that is connected with the secret of human development. The fact that such pictures are made does not merely arise from a need for a sensualisation of supersensible processes, but corresponds to the fact that living into these pictures - if they are the right ones - really means an arousal of forces which lie dormant in the human soul, and through the awakening of which the ideas of the supersensible world emerge. For it is not right in Theosophy to describe the supersensible worlds only in schematic terms; the true way is to arouse the imagination of such images as are given in these seals. (If the occultist has no such pictures at hand, he should give orally the description of the higher worlds in pertinent images).“ (Lit.:GA 34, p. 596f)

Imagination and the human organism

The same forces which are active in the human organism from the fourteenth to the twenty-first year of life, and which fire the youthful ideals, are also active in the imagination:

„... those forces which in former times entered into men from the fourteenth to the twenty-first year the youthful ideals - it would be too much to assert that they still do so now - and created organs in the physical body for these youthful ideals, these are the same forces which are then called forth from their dormant state and can effect the imagination.“ (Lit.:GA 191, p. 33)

Path of spiritual training

Through spiritual training, a preliminary form of imaginative consciousness can already be attained today. For this, the consciousness soul must be transformed into the imagination soul. Imagination is the second stage of Rosicrucian initiation.

„The etheric body is in regular movement throughout the rest of the human body, except in the head. In the head the etheric body is inwardly calm. In sleep it is different. We still perceive the last etheric movements of the head when we wake up - the dreams. Whoever meditates for a long time in the way I have indicated, however, comes into the position of gradually forming images in the quiet etheric body of the head. That is what I call imaginations. And these imaginations, which are experienced independently of the physical body in the etheric body, are the first supersensible impression we can have.“ (Lit.:GA 305, p. 82)

In order to develop imaginative consciousness, one must first learn to look at the world according to the line of verse from Goethe's Faust: All that is transient is only a parable. One begins to experience the sensual-moral effect of the sensual qualities. Through imagination we learn to experience perceptions of colour, sound, taste, smell as external expressions of spiritual entities. Imaginatively we see the etheric body and astral body of spiritual beings, as it were their supersensory outside. The spiritual essence remains hidden from the imagination.

The seed meditation from CW 10 can be considered particularly suitable for achieving the first imaginations.

The red west window of the first Goetheanum

Rudolf Steiner described the imagination in pictorial form in the motifs of the red west window of the first Goetheanum.

The path to imaginative knowledge was shown in the left side window. The warming red, in which the ether of warmth manifests itself, permeates the whole picture. One sees a bright figure that has climbed a high rock and is directing its gaze and its arms downwards towards three grotesque bird-like or snake-like animal-like figures that stretch upwards threateningly; the one on the right even shows a human-like face. This is the lower soul nature of man, the trinity of the still unpurified soul forces of thinking, feeling and willing, in which lower, animal astral forces still work. At the same time, it is also an image for the still imperfect soul members: the sentient soul, the intellectual or mind soul and the consciousness soul. If the spiritually striving person succeeds in detaching himself from this lower nature and looking at it objectively from the outside, the imagination can light up.

In the middle part of the window the already awakened faculty of imagination is depicted. The human face shown here bears the sign of the two-petalled lotus flower on the forehead, which is already activated. The eye area is particularly emphasised, the power of spiritual seeing, of imagination has awakened, because the experiences of the forehead chakra are expressed in the light ether part of the human etheric body.

Next to it, on the upper left and right, you can see two winged angelic beings belonging to the first hierarchy. The left angelic figure shows the sign of the moon, the right one the symbol of the sun and above the human head Saturn. This refers to the planetary stages of development that preceded the earth's existence, to the Old Saturn, where man received the physical body, to the Old Sun, which gave man the etheric body, and finally to the Old Moon, the planet of wisdom, on which man received his astral body.

Below this, two figures with animal heads are seen on the left and on the right, apparently murmuring something into man's ear. This already points to a sound experience. The sound ether resounds. These two beings belong to the second hierarchy. The left figure wears a lion's head, symbolising the etheric forces; the right figure has a bull's head, a sign for the physical world.

In the throat area the throat chakra is visible, which already points to the inspired knowledge. The spiritual experiences are now also expressed in the word or life ether. Below this, Michael, the most important representative of the third hierarchy, can be seen fighting and forcing down the dragon, the lower nature of man.

In the right-hand side window, man is shown after he has attained the faculty of imagination. Again we see the bright human figure on the top of the towering rock, here its arms and gaze are now turned towards the spiritual sun, which fills the uppermost part of the picture with its radiant glow. Between the human being and the animals in the abyss hover three pairs of angels who hold out their hands to each other. At the same time they represent the purified higher soul forces of the human being. In their bosom they also carry the higher spiritual members of the human being: the spirit self, the life spirit and the spirit man. Together with the human being at the top, the three pairs of angels form an image of the sacred number seven. The animal figures from the depths have receded, the one with the human face has even disappeared completely. The consciousness soul has transformed itself into the imagination soul through spiritual training.

Imaginative thinking

When we think in the physical world, we use the etheric body, whose activity is reflected back to our consciousness by the physical body, namely by the brain respectively the nervous system. If we pass over to imaginative thinking, the thinking activity is transferred back into the astral body and mirrored in the etheric body.

„It is necessary to make these things clear to oneself, for it is only then that one learns to recognise from what enormous errors the thinking of the present suffers, with what a sum of errors this thinking of the present fools itself, and how a recovery must take place through that more difficult knowledge which does not take any account of the physical body: if we walk with the physical body, we must have the ground under our feet; if we think in the physical world, we must have an abutment as a ground for thinking: the nervous system. But if we transfer our thinking back to our astral body, then the etheric body becomes for us what the physical body is when we think in the etheric body.

If we proceed to imaginative thinking, then we think in the astral body, and the etheric body then retains the traces, as otherwise, when thinking in the etheric body, the physical body retains the traces. And when we are outside the physical body after death and have also laid aside the etheric body, as has often been described, then our counterpart is the outer life ether, then we inscribe that which the astral body and later the I develops into the whole world ether.

This is the process we go through in what is called the first stage of initiation. This process is that we transfer our thinking back - it does not remain thinking, it is only the activity of thinking - that we transfer our thinking back from the etheric body into the astral body, and impose the storage of the traces, which was formerly the responsibility of the physical body, on the more fleeting etheric body. This is the essence of the first step of initiation: the transferring back to the astral body of this activity which was previously performed by the etheric body.

Thus we see that while we live in imaginative knowledge, we withdraw, as it were, from the physical body to the etheric body, and then leave no further traces in the physical body. Thus it happens that for the one who goes through these first steps of initiation, this physical body from which he withdraws becomes objective, that he now has it outside his astral body and I. He used to be in it; he used to be in the etheric body. Formerly he was in it; now he is outside it. He thinks, feels and wills in the astral body. He influences the etheric body, makes traces in it; but he no longer influences the physical body, which he now sees as something external. This is, so to speak, the normal course in relation to the first steps in initiation. It expresses itself in the subjective experience in a quite definite way.

Now I want to show you first through a kind of schematic drawing to make clear what these first steps of initiation consist of.

Let us assume that this is the human physical head, so the etheric body is around this human physical head. When man begins to develop what I have spoken of, when he begins to develop imaginative knowledge, then the etheric body enlarges in this way, and the peculiar thing is that naturally the phenomena which we have described as the formation of the lotus flowers go parallel to this. The human being grows, as it were, ethereally out of himself, and the peculiar thing is that the human being, in growing ethereally out of himself, develops something similar outside his body, I would say, like a kind of etheric heart.

As physical human beings we have our physical heart, and we all appreciate the difference between a dry, abstract human being who develops his thoughts like a real machine, and a human being who is with his heart in everything he experiences; I mean, is with his physical heart. We all appreciate this difference. We do not expect much of the dry lurker, who is not with his heart in what he experiences in the soul, in terms of real knowledge of the world on the physical plane. A kind of spiritual heart, which is outside our physical body, forms parallel to all the phenomena I have described in "How does one attain knowledge of the higher worlds? ", just as the blood network is formed and has its centre in the heart. This network goes outside the body, and we then feel warmly connected outside the body with that which we recognise spiritually. Only it is not necessary to demand that the human being be present, as it were, with the heart which he has in the body, in spiritual-scientific cognition, but with the heart which becomes him outside the body; with this he is cordially present with that which he cognizes spiritually-scientifically.“ (Lit.:GA 161, p. 241ff)

„All that I have now described as the normal course to clairvoyance consists in the fact that man lifts his etheric body, even the higher members of the organisation, out of the physical body, that he incorporates a heart outside the circumference of the physical body.

On what, then, are the ordinary thoughts based? You see, such a thought is really only developed in the etheric body; but now it comes up against the physical body, it makes impressions everywhere in the brain within it. If we consider the essentials of everyday thought, we can say that it is based on the fact that we think in the etheric body, and that what we think falls on the nervous system of the brain; it makes impressions there, but these impressions do not go deep, they rebound. And through this the thought is reflected, through this it comes to our consciousness. So a thought consists at first in this, that we have it in the soul as far as the etheric body; then it makes an impression on the physical brain, but it cannot enter there and must therefore rebound. We perceive these rebounded thoughts. And that is where physiology comes in and shows the traces that have arisen in the physical brain.

What would it be, then, if the thought did not rebound, but if it entered the brain and merely caused processes within it? If it did not rebound, we could not perceive it; then it would go into the brain and simply cause processes there. It is conceivable that the thought, instead of being thrown back, might go into the brain. Then we would have no consciousness, for consciousness arises only when the thought is reflected.

But there is such an activity of the soul that goes into the body: that is volition. Volition differs from thinking in that thinking bounces back against the body's organisation and is perceived in the mirror image, but volition does not. With the will it is so that it goes into the bodily organisation, and a physical bodily process is then brought about. This causes us to walk or move our hands and so on. The actual will arises in a completely different way than the thought. The thought comes into being by bouncing back. The will, however, enters into the body's organisation, is not thrown back, but causes certain processes in the body's organisation.

But in one part of our bodily organisation there is still the possibility that something which is submerged there will rebound again. Follow what I am going to say. In our cerebral thinking it happens in such a way that thought activity develops in the etheric brain, rebounding on the physical nervous system, and that through this the thoughts come to our consciousness. In clairvoyance we push back the brain, as it were. We think with the astral body, and thought is already thrown back to us by the etheric body. Here (see Drawing I) is the outer world, here the physical body (when thinking in the brain); here in clairvoyance the outer world, that which we process with the astral body (see Drawing II); we allow the etheric body to throw it back, and we leave the physical body completely switched off.

But here (see drawing I), if we want, the activity of the soul dives into the physical body. Therefore, when we walk, move our hand, it is the soul that does this. But its activity must bring about inner, organic, material processes, and in these the activity of the soul lives itself out. I would like to say that the will consists in the fact that the activity of the soul dies out in the material activity in the body.

Now ask yourself: How do we actually live when we live in our thinking? I would like to say that in our thinking we live close to the boundary of eternity. The moment we switch off the physical body and let our thoughts radiate back from the etheric body, we live in that which we carry through the gate of death. As long as we allow our thoughts to radiate back from the physical body, we live in what is there between birth and death. But when we want, our wanting belongs only to our physical body. Our physical body is there so that it can develop activity. While thinking is, so to speak, already at the gate of eternity, willing is endowed for the physical body.

Remember that I said in one of the lectures: The will is the baby, and when it grows older it becomes thought. That agrees with what we can develop today from another point of view. The will is banished into temporality, and only by developing himself, by becoming wiser and wiser, by penetrating his will more and more with thoughts, does he raise that which is born in the will out of temporality into the sphere of eternity, does he release his will from his body.

But in one part of his body something is switched on: the subordinate nervous system, the ganglionic system, the abdominal nervous system; the solar plexus is often also called a part of it. This nervous system, as it is now developing in man, is an imperfect organ; it is only present in the very first stages. Later it will develop further. But just as we know from a child that it can still develop the qualities which it develops as an adult, so we can know that this nervous system, which today serves to supply organic activities, will still develop. This nervous system, which runs alongside the actual brain and spinal cord system and alongside the nerves branching out in the limbs, this abdominal nervous system is not yet so developed today that it could do what it will do when man will one day be on Jupiter. There the brain and the spinal cord will be degenerated, and the abdominal nervous system will have quite a different development from what it has today. Then it will be stored on the surface of the human being. For everything that is first in the human being will later be deposited on the surface of the human being.

For this reason, however, we do not use this nervous system directly for the ordinary life between birth and death; we leave it in the subconscious. But it can happen through abnormal conditions that that which lies in the human will and in the faculty of desire enters the human organism, and that through abnormal conditions, about which we shall speak, it is thrown back by the abdominal nervous system, just as otherwise thought is thrown back by the brain. The will enters the ganglionic system, but instead of becoming activity, it is thrown back by the ganglionic system, and something arises in the human being which otherwise arises in the brain. A process arises in the human being which can also be characterised in this way: If you consider the transition from the ordinary waking state to clairvoyance, you can see how our thinking, feeling and willing are reflected in us in the ordinary nervous system - feeling and willing in so far as they are thoughts - but that which is willing we let submerge into the organisation.

In clairvoyance we form - outside the bodily space, so to speak - an organ higher than the brain. Just as our ordinary brain is connected with our physical heart, so that which develops as thought outside, in the astral sphere, is connected with this etheric heart. That is higher clairvoyance: Head clairvoyance.

But man can also go the other way. He can enter into the organisation with what is in the "baby" will in such a way that the will becomes a thinking, whereas otherwise he has made the thinking into the will. This is the deeper reason for what I mentioned some time ago as the difference between head clairvoyance and gut clairvoyance. In head clairvoyance a new etheric organ is formed in which one becomes independent of the body organisation. In gut clairvoyance one appeals to the ganglionic system, one appeals to that which otherwise remains unconsidered. Therefore, the results of gut clairvoyance are more fleeting than the ordinary waking experiences, they have no meaning for the souls when they pass through the gate of death. Everything that is gained through head clairvoyance has a spiritual, lasting significance also for the souls that have passed through the gate of death, has more significance than the waking daytime experience. That which is gained through gut clairvoyance has even less significance for the life after death than everyday waking knowledge. Every somnambulic clairvoyance is below the waking day-consciousness, not above it. The fact that all kinds of poetic and other qualities can be developed through abdominal clairvoyance is not at all contradictory, because at the moment when this abdominal clairvoyance occurs, it is really the ganglia which always pass the will into the physical body. Thus the activity of the etheric body is held back in the ganglia and radiates back, and through this one then perceives that which one cannot perceive through the brain. One can thereby perceive thoughts that one otherwise cannot perceive through the brain; but it still remains a subordinate activity.“ (Lit.:GA 161, p. 244ff)

How are imaginations experienced?

When the imagination develops in the disciple, the imaginations first resemble the memory images and then also the dream images. They are pale and indeterminate, but not chaotically jumbled like the dream images. But one gradually learns to distinguish the real imaginations from the reminiscences of what one has experienced in sensual existence and also from dreams.

„Man in ordinary consciousness can only dream egoistically. When he dreams at night, he dreams in bondage to his own organism; in the dream he is not connected with his surroundings. If he can be connected with the surroundings and develop the same forces that he otherwise develops in dreams, he is in imaginative conception.“ (Lit.:GA 179, p. 106)

Imaginations are not only images in the human soul, but they belong to spiritual reality. Ultimately, everything is created from imaginative images, including the physical world. They are the effectively active archetypes of things. They are the ideas, the archetypes in Plato's sense. The primordial plant, of which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe spoke in his metamorphosis theory, is an example of this. (Lit.:GA 157, p. 298)

Painting seeing

The Austrian physicist and co-founder of quantum theory Wolfgang Pauli (1900-1958) had a very clear inkling of this when, in a letter to the physicist Markus Fierz (1912-2006) in which he refers to his lecture "On Physical Knowledge" published in the Eranos Yearbook in 1948, he speaks very accurately in this regard of a painting seeing or painting looking of these inner images:

„The ideas formulated in your lecture have many points of contact with mine, e.g. complementarity and universality, or physics and psychology, but perhaps there are also some differences. My starting point is what is the bridge between sense perceptions and concepts. Admittedly, logic cannot give or construct such a bridge. If one analyses the preconscious stage of concepts, one always finds concepts consisting of "symbolic"[3] images with generally strong emotional content. The preliminary stage of thinking is a painting seeing of these inner images, the origin of which cannot be attributed solely and not primarily to the sense perceptions (of the individual concerned), but which are produced by an "instinct of imagining" and reproduced independently, i.e. collectively, in different individuals. (What you said on pages 12 and 13 about the concept of number fits in with this.) The former archaic-magical standpoint is only a little below the surface; a slight abaissement du niveau mental is enough to make it come completely "up". But the archaic attitude is also the necessary condition and source of the scientific attitude. To a complete cognition belongs also that of the images from which the rational concepts have grown.

Now comes a view where I am perhaps more of a Platonist[4] than the psychologists of the Jungian direction. What is now the answer to the question of the bridge between sense perceptions and concepts, which is now reduced to us to the question of the bridge between external perceptions and those internal pictorial conceptions. It seems to me - however one turns it, whether one speaks of the "participation of things in ideas" or of "things real in themselves" - a cosmic order of nature must be postulated here, withdrawn from our arbitrariness, to which both the external material objects and the inner images are subject. (Which of the two is historically the earlier is likely to prove an idle joking question - something like "Which was earlier: the chicken or the egg?") The ordering and regulating must be placed beyond the distinction of physical and psychic - just as Plato's "ideas" have something of "concepts" and also something of "natural forces" (they produce effects of their own accord). I am very much in favour of calling this "ordering and regulating" "archetypes"; but it would then be inadmissible to define these as psychic contents. Rather, the inner images mentioned ("dominants of the collective unconscious" according to Jung) are the psychic manifestation of the archetypes, which, however, would also have to produce, generate, condition everything natural in the behaviour of the body world. The natural laws of the bodily world would then be the physical manifestation of the archetypes.“ (Lit.: Meyenn, p. 496f)

For Plato, the source of these archetypal ideas is "the good", as he presents it, for example, in the analogy of the sun in in the sixth book of The Republic (507b–509c):

„As goodness stands in the intelligible realm to intelligence and the things we know, so the sun stands in the visible realm to sight and the things we see.“

In imagining, the soul, based on attentive sensual observation, moves with the world events, as Anton Kimpfler emphasises:

„Imagining can be described as painting with the eyes themselves. It does not remain with the registration of a certain colour. Rather, a more immediate encounter with it takes place. We participate in it more actively.

The outer becomes more inner, that is how this could also be characterised. The soul moves with the world events. The exact opposite is achieved by technical media, through which our relationship to the world is even more cut off.“ (Lit.: A. Kimpfler, p. 41)

Goethe, for example, was able to immerse himself in the inner process of plant growth by carefully observing it and condensing it into the imagination of the archetypal plant.

The image-creating power of the soul also reveals itself in dreams. We are, however, more or less voluntarily given over to the dream images, which represent a last remnant of atavistic clairvoyance. In lucid dreams our will is already more actively switched on, and in waking we then already relate to our environment very clearly by will. The more our will accompanies the seeing, the more we also feel confronted with an actual reality. This increases even more when we progress to imagination. Both our engagement of will and our sense of reality are significantly heightened compared to ordinary waking consciousness. The consciousness is more awake and clear than the normal daytime consciousness. We know that we ourselves make the images - and yet they are not arbitrary, but the appropriate expression of a higher reality.

„First of all, however, the soul must make itself ready to see such images appear in the spiritual circle of vision; for this purpose, however, it must also carefully develop the feeling not to stop at these images, but to relate them in the right way to the supersensible world. One can certainly say that true supersensible perception includes not only the ability to see a world of images within oneself, but another which can be compared with reading in the sensuous world.

The supersensible world must first be imagined as something quite beyond ordinary consciousness. This consciousness has nothing by which it can approach this world. Through the powers of the soul life, which are strengthened in meditation, a contact of the soul with the supersensible world is first created. Through this, the marked images emerge from the floods of the soul life. These are as such a tableau, which is actually woven entirely by the soul itself. It is woven from the forces that the soul has acquired in the sensual world. As a pictorial fabric, it really contains nothing other than what can be compared to memory. - The more one makes this clear for the understanding of clairvoyant consciousness, the better it is. One will then have no illusions about the nature of the image. And in this way one will also develop a right feeling for the way in which one has to relate the images to the supersensible world. One will learn to read through the images in the supersensible world.“ (Lit.:GA 17, p. 18)

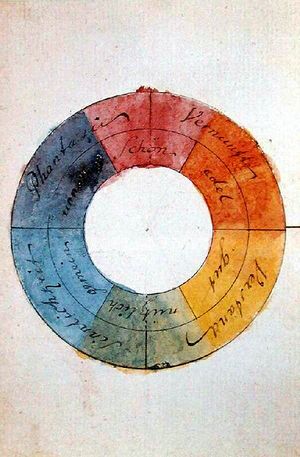

Goethe's Theory of Colours as a basis for understanding the supersensible colors of the aura

The sensual perception of color is inseparable from an emotional undertone that accompanies it, which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe refers to as the "sensual-moral effect of color". But this is by no means a purely subjective experience. Both, the perceived color and the accompanying emotional undertone, originate as a whole from the essence of the respective color. Although the fine undertone of the externally perceived color can only be experienced subjectively inwardly mentally by the observer, it nevertheless does not depend on the observer's personal idiosyncrasy and insofar has at the same time an objective character. Certain color combinations arouse quite specific mental effects. These are of decisive importance for the artistic handling of color.

„Goethe starts from the physiological colors; I have shown you this when I characterized his way of coming to knowledge by other methods of investigation than the present methods of investigation. Then, however, his whole approach culminates in the chapter which he called "Sensual-moral effect of color". There Goethe goes, so to speak, directly from the physical into the spiritual, and he then characterizes the whole spectrum of colors with an extraordinary accuracy. He characterizes the impression that is experienced; it is, after all, something that is experienced quite objectively. Even if it is experienced in the subject, it is nevertheless something thoroughly objectively experienced in the subject, the impression which, let us say, the colors situated towards the warm side of the spectrum make, red, yellow. He describes them in their activity, how they, so to speak, have an exciting or stimulating effect on man. And he describes how then the colors which are situated towards the cold side have a stimulating effect, incite to devotion; and he describes how the green in the middle has a balancing effect.

So, in a sense, he is describing a spectrum of feelings. And it is interesting to visualize, how a soul-differentiated immediately jumps out of the ordered physical way of looking at things. Whoever understands such a course of investigation comes to the following results. He says to himself: The individual colors of the spectrum stand before us, they are experienced as entities which appear to be quite separate from man. In the ordinary perception of life we quite naturally and justifiably attach the greatest importance to directly grasping this objective element, let us say in the red, in the yellow. But there is an undertone everywhere. If we look at the immediate experience, it can only be separated in abstraction from that which is a so-called experience of the red nuance and the blue nuance, separated from the human being externally, in an objective sense; It is an abstract separation from that which is also directly experienced in the act of seeing, but which is only struck, which is, so to speak, experienced in a quiet undertone, but which can never remain away, so that in this field one can only look at it purely physically, if one first abstracts that which is experienced mentally from the physical.

So we have first the outer spectrum, and we have at this outer spectrum the undertone of the mental experiences. So we stand with our senses, with the eye, opposite the outer world, and we cannot adjust the eye in any other way than that mostly, even if often even unconsciously or subconsciously, soul experience runs along with it. We call what is experienced through the eye sensation. We are now accustomed, my dear present ones, to call that which is experienced at the sensation, which is experienced soulishly - at which a stimulus, which originates from the objectively spread out, presents itself as sensation - the subjective. But you see from the way in which I have just presented this, following Goethe, that we can, so to speak, set up a counter-spectrum, a soul counter-spectrum, which can be brought into parallel quite exactly with the outer optical spectrum.“ (Lit.:GA 73a, p. 254ff)

The "sensual-moral effect of color" described by Goethe can contribute to a better understanding of what the clairvoyant experiences, for example, imaginatively as color qualities of the aura.

„We can set up a spectrum of differentiated feelings: exciting, stimulating, balancing, devotional, and so on. If we look outward, we see the yellow; we sense from it as an undertone the stimulating, that which, as it were, actively acts upon us from the outside. What is the situation with the spiritual experience? This spiritual experience comes, as it were, from our inner being towards the outer world. But let us assume that we would be able to record exactly what we have experienced in the red, the yellow, the green, the blue, the violet. Let us assume that we would be able to record the feelings in a differentiated way so that we have a spectrum of feelings inside, like we have the usual optical spectrum from the outside. If we now imagine that from the outside the red, yellow, green, blue, violet, i.e. the objective, ignite the undertones of excitement, stimulation, compensation, devotion, we thus see it, so to speak, as something accompanying the outer appearances. Would it then be something so absurd to assume that also from within that could happen, which otherwise is the basis of this spectrum of feelings without our intervention from the outside? Would it be something so absurd that now the spectrum of feelings would be there inside and from it would spring forth in the experience of man the spectrum of colors which is now grasped in inner images? Just as otherwise the color spectrum is there and the inner emotional experiences are added by our being present, so it could also be that the emotional experiences, which can be represented in the differentiated spectrum, would be regarded as the objective, the inwardly located objective, and now jumps out as an undertone that which can now be compared with the objective color spectrum.

Now spiritual science claims nothing else than that a method is possible where what I have now presented to you as a postulate is really experienced [inwardly] as from the outer experience where the objective spectrum is there and, as it were, the subjective spectrum of feelings is drawn as a veil over the objective spectrum. In the same way, the spectrum of feelings can now be experienced inwardly, which is now followed by the experience of color. This can really be experienced, and it underlies what I characterized yesterday more abstractly as the imagination. That which is a phenomenon spread out in space, an outer phenomenon, can also be brought out of the human being as an inner phenomenon. And as the outer phenomenon dilutes towards us in cognition, so the inner experience condenses by being taken up by the consciousness unconsciously developed in us - as I indicated yesterday.

It is only necessary to be clear, my dear audience, that what appears in the spiritual science meant here are by no means nebulous fantasies, as are usually the results of some reveries known as "mystical world views". What is meant here as anthroposophical spiritual science is based on experiences which one does not have otherwise, which must first be developed, but which can be grasped in absolutely clear terms, which can be followed everywhere with absolutely clear terms.

One can therefore say that Goethe depicted the objectively external in the same way as a person who is half instinctively aware: There is an inner counter-image of what he describes externally; there is an inner view to the external view.