Pure thinking: Difference between revisions

| (15 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

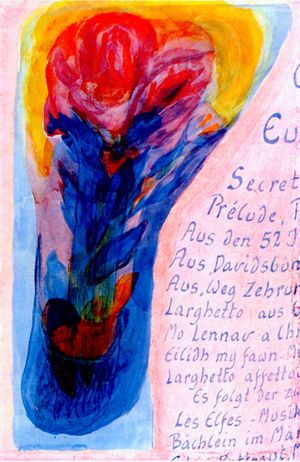

[[File:William Turner, Light and Colour (Goethe's Theory).JPG|thumb|[[Wikipedia: | [[File:William Turner, Light and Colour (Goethe's Theory).JPG|thumb|[[Wikipedia:J. M. W. Turner|Joseph Mallord William Turner]], Light and Colour (Goethe's Theory) - the Morning after the Deluge, Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843)]] | ||

'''Pure thinking''' ({{Latin|intellectus purus}}) is creative, active, '''living thinking''' and thus at the same time pure [[will]], i.e. pure spiritual activity. It is the beginning of direct spiritual experience. Its content are at first pure [[concept]]s without direct reference to sensual perceptions and the reciprocal lawful relationships to each other resulting from the concepts themselves, which reveal themselves holistically in pure forms and structures free of sensuality. Pure thinking thus differs from the usual discursive activity of understanding, through which we try to penetrate sensual experiences by thinking and combine ready-made concepts with one another according to logical criteria or formally derive them from one another through logical conclusions. We use the [[physical]] [[brain]] as a tool in the activity of understanding. Although it is not the brain that thinks, the brain reflects our own mental activity back to us in the form of intellectual [[thought]]s and only thereby brings them to our [[consciousness]]. Through the unprejudiced mind we can, as [[Rudolf Steiner]] has repeatedly emphasised, grasp spiritual content in principle, but we cannot experience it directly. This only becomes possible through pure, sensuality-free thinking, which presupposes bodiless experience and is thus at the same time '''[[#Body-free thinking|body-free thinking]]'''<ref>Pure thinking does not gain its content through abstraction from the sense world, but directly from the purely spiritual, essential world of ideas; in order to be able to hold and communicate this content in the form of factual thoughts, however, the tool of the brain is most certainly necessary. In this sense, "free of the body" means that nothing of the activity of the body flows into the content of pure thinking.</ref>, through which the [[spirit self]] is already formed as the higher spiritual element of the human being {{GZ||53|214f}}. | '''Pure thinking''' ({{Latin|intellectus purus}}) is creative, active, '''living thinking''' and thus at the same time pure [[will]], i.e. pure spiritual activity. It is the beginning of direct spiritual experience. Its content are at first pure [[concept]]s without direct reference to sensual perceptions and the reciprocal lawful relationships to each other resulting from the concepts themselves, which reveal themselves holistically in pure forms and structures free of sensuality. Pure thinking thus differs from the usual discursive activity of understanding, through which we try to penetrate sensual experiences by thinking and combine ready-made concepts with one another according to logical criteria or formally derive them from one another through logical conclusions. We use the [[physical]] [[brain]] as a tool in the activity of understanding. Although it is not the brain that thinks, the brain reflects our own mental activity back to us in the form of intellectual [[thought]]s and only thereby brings them to our [[consciousness]]. Through the unprejudiced mind we can, as [[Rudolf Steiner]] has repeatedly emphasised, grasp spiritual content in principle, but we cannot experience it directly. This only becomes possible through pure, sensuality-free thinking, which presupposes bodiless experience and is thus at the same time '''[[#Body-free thinking|body-free thinking]]'''<ref>Pure thinking does not gain its content through abstraction from the sense world, but directly from the purely spiritual, essential world of ideas; in order to be able to hold and communicate this content in the form of factual thoughts, however, the tool of the brain is most certainly necessary. In this sense, "free of the body" means that nothing of the activity of the body flows into the content of pure thinking.</ref>, through which the [[spirit self]] is already formed as the higher spiritual element of the human being {{GZ||53|214f}}. | ||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

This difference that you feel between touching a dead object and a living object, you must realise. When you touch a dead object, you have a different feeling than when you touch a living one. Now, if you have an idea on the physical plane, you have a feeling that you can compare with touching a dead object. But as soon as you really come down below the threshold of consciousness, this changes; so that you get the feeling: The thought has life inside, begins to stir. It is the same discovery you have - as a comparison for the psychic feeling - as when you have grasped a mouse for my sake: the thought tingles and crawls.|164|36ff}} | This difference that you feel between touching a dead object and a living object, you must realise. When you touch a dead object, you have a different feeling than when you touch a living one. Now, if you have an idea on the physical plane, you have a feeling that you can compare with touching a dead object. But as soon as you really come down below the threshold of consciousness, this changes; so that you get the feeling: The thought has life inside, begins to stir. It is the same discovery you have - as a comparison for the psychic feeling - as when you have grasped a mouse for my sake: the thought tingles and crawls.|164|36ff}} | ||

=== Formative thinking === | |||

[[File:Urpflanze.jpg|thumb|[[Rudolf Steiner]], [[archetypal plant]], watercolor 1924]] | |||

{{GZ|There are two ways of forming thoughts. One is the dissecting, the discriminating, which plays such a great role today, especially in natural science, where one distinguishes, carefully distinguishes. You will find that it is precisely in natural science that this sets the tone. Everything that is said, written and done in natural science is under the influence of the dissecting way of thinking, the discriminating way of thinking. Tight definitions are sought. And if someone says something today, he is nailed to strict definitions. But strict definitions are nothing more than distinctions between the things one defines and other things. This way of thinking is a kind of mask that the spirits who want to tear us apart today, who are in the middle of this struggle, like to use. Trivially, one could say that a large number of those people who have brought about the present war catastrophe and those who are still involved in the consequences are actually crazy. But this is, as I said, only something trivial. What it is about is understanding what is tearing their personalities apart. From this way of thinking, to which the various powers that tear people apart have access, one must clearly distinguish the other, which is used in spiritual science alone. It is a quite different type of conception, a quite different way of thinking. In contrast to the dissecting way of thinking, it is a formative way of thinking. Look more closely, follow what I am trying to say in the various books on spiritual science, and you will say to yourself: the difference is not so much in what is communicated - that can be judged either way - but you should become attentive to the fact that the whole way of integrating the whole world, the whole way of conceiving it, is a different one. This is formative, it gives self-contained pictorialities, it tries to give contours and, through contours, colours. You will be able to follow this throughout the whole presentation: it does not have the dissecting quality that all present-day science has. This difference of how must be emphasised just as much as the difference of what. So there is a formative way of thinking which is being developed in particular and which has the purpose of leading into the supersensible worlds. If you take, for example, the book "How to attain knowledge of the higher worlds", where such a path into the supersensible worlds is outlined, you will find that in it everything that engages the thoughts and ideas is predisposed to formative thinking. | |||

This is something that is necessary for the present. For formative thinking has a very definite quality. If you think in a dissecting way, if you think as the naturalist of today thinks, then you think in the same way as certain spirits of the ahrimanic world, and therefore these ahrimanic spirits can penetrate your soul. But if you take the formative thinking, the metamorphosed thinking, I could also say the Goethean thinking, as it presents itself, for example, in the design of our columns and capitals and so on, if you take this formative thinking, which is also observed in all the books that I tried to introduce into spiritual science, then this thinking is closely bound to the human being. No other beings than those who are connected with the normal development of humanity are able to shape thinking in the way that the human being does. That is the peculiarity. This means that you can never take the wrong path when you engage in creative thinking through spiritual science. You can never lose yourself to the various spiritual beings who want to influence you. Of course, they will pass through your being. But as soon as you think creatively, as soon as you make an effort not merely to spint and to distinguish, but to think as this modern spiritual science really wants you to think, then you remain within yourself, then you cannot have the feeling of being merely hollowed out. That is why, if you stand on the standpoint of our spiritual science, you so often emphasise the Christ-impulse, because the Christ-impulse lies in the straight line of formative thinking. The Gospels cannot be understood by merely dissecting them. Modern Protestant theology has shown what results from this. It dissects, but it has also lost everything, and nothing has remained. Those cycles that deal with the Gospels follow the opposite path. They build up something that is shaped in order to advance to the understanding of the old Gospels through these new shapes. Today - and this is not at all an exaggeration - it is not necessary for anyone to do anything other than to adhere to the way of thinking of this spiritual science, then those demonic beings which roll in with the new wave as concomitants of the Spirits of Personality cannot harm him. Hence you see what a great harm it actually is to humanity if it resists This is something that is necessary for the present. For formative thinking has a very definite quality. If you think in a dissecting way, if you think as the naturalist of today thinks, then you think in the same way as certain spirits of the ahrimanic world, and therefore these ahrimanic spirits can penetrate your soul. But if you take the formative thinking, the metamorphosed thinking, I could also say the Goethean thinking, as it presents itself, for example, in the design of our columns and capitals and so on, if you take this formative thinking, which is also observed in all the books that I tried to introduce into spiritual science, then this thinking is closely bound to the human being. No other beings than those who are connected with the normal development of humanity are able to shape thinking in the way that the human being does. That is the peculiarity. This means that you can never take the wrong path when you engage in creative thinking through spiritual science. You can never lose yourself to the various spiritual beings who want to influence you. Of course, they will pass through your being. But as soon as you think creatively, as soon as you make an effort not merely to spint and to distinguish, but to think as this modern spiritual science really wants you to think, then you remain within yourself, then you cannot have the feeling of being merely hollowed out. That is why, if you stand on the standpoint of our spiritual science, you so often emphasise the Christ-impulse, because the Christ-impulse lies in the straight line of formative thinking. The Gospels cannot be understood by merely dissecting them. Modern Protestant theology has shown what results from this. It dissects, but it has also lost everything, and nothing has remained. Those cycles that deal with the Gospels follow the opposite path. They build up something that is shaped in order to advance to the understanding of the old Gospels through these new shapes. Today - and this is not at all an exaggeration - it is not necessary for anyone to do anything other than to adhere to the way of thinking of this spiritual science, then those demonic beings which roll in with the new wave as concomitants of the Spirits of Personality cannot harm him. Hence you see what a great harm it actually is to humanity if it resists This is something that is necessary for the present. For formative thinking has a very definite quality. If you think in a dissecting way, if you think as the naturalist of today thinks, then you think in the same way as certain spirits of the ahrimanic world, and therefore these ahrimanic spirits can penetrate your soul. But if you take the formative thinking, the metamorphosed thinking, I could also say the Goethean thinking, as it presents itself, for example, in the design of our columns and capitals and so on, if you take this formative thinking, which is also observed in all the books that I tried to introduce into spiritual science, then this thinking is closely bound to the human being. No other beings than those who are connected with the normal development of humanity are able to shape thinking in the way that the human being does. That is the peculiarity. This means that you can never take the wrong path when you engage in creative thinking through spiritual science. You can never lose yourself to the various spiritual beings who want to influence you. Of course, they will pass through your being. But as soon as you think creatively, as soon as you make an effort not merely to spint and to distinguish, but to think as this modern spiritual science really wants you to think, then you remain within yourself, then you cannot have the feeling of being merely hollowed out. That is why, if you stand on the standpoint of our spiritual science, you so often emphasise the Christ-impulse, because the Christ-impulse lies in the straight line of formative thinking. The Gospels cannot be understood by merely dissecting them. Modern Protestant theology has shown what results from this. It dissects, but it has also lost everything, and nothing has remained. Those cycles that deal with the Gospels follow the opposite path. They build up something that is shaped in order to advance to the understanding of the old Gospels through these new shapes. Today - and this is not at all an exaggeration - it is not necessary for anyone to do anything other than to adhere to the way of thinking of this spiritual science, then those demonic beings which roll in with the new wave as concomitants of the Spirits of Personality cannot harm him. Hence you see what a great harm it actually is to humanity if it resists the spiritual scientific way of thinking.|187|176ff}} | |||

=== Living thinking as an ascent from the realm of the Spirits of Form to that of the Spirits of Motion === | |||

{{GZ|Man experiences in himself what we can call the thought, and in the thought man can feel himself as something directly active, as something that can survey his activity. If we look at some external thing, for example a rose or a stone, and we imagine this external thing, someone can rightly say: You can never actually know how much you actually have of the thing, of the plant, in the stone or in the rose by imagining it. You see the rose, its outer redness, its form, how it is divided into individual petals, you see the stone with its colour, with its various corners, but you must always say to yourself: there may still be something inside that does not appear to you on the outside. You don't know how much you actually have in your imagination of the stone, of the rose. | |||

But when someone has a thought, it is he himself who makes that thought. One might say that he is inside every fibre of his thought. Therefore, for the whole thought, he is a participant in its activity. He knows that what is in the thought is what I have thought into the thought, and what I have not thought into the thought cannot be in it. I survey the thought. No one can assert that, when I present a thought, there could be so and so much else in the thought as in the rose and in the stone; for I myself have produced the thought, am present in it, and thus know what is inside. | |||

Really, the thought is our very own. If we find the relationship of thought to the cosmos, to the universe, then we find the relationship of our very own to the cosmos, to the universe... So what has just been said promises us that the human being, if he keeps to what he has in thought, can find an intimate relationship of his being to the universe, to the cosmos. | |||

But there is a difficulty, a great difficulty, if we want to look at it from this point of view. I don't mean for our contemplation, but for the objective facts it has a great difficulty. And this difficulty consists in the fact that it is true that one lives inside every fibre of thought and must therefore know the thought, if one has it, most intimately before all ideas; but, yes but - most people have no thoughts! And this is not usually thought through with all thoroughness, that most men have no thoughts. For the reason that it is not thought through with all thoroughness, because for this - thoughts are needed! One thing must first be pointed out. What prevents people in the widest circle of our life from having thoughts is that for the ordinary use of life people do not always have the need to really penetrate to the thought, but that instead of the thought they are content with the word. Most of what is called thinking in ordinary life takes place in words. One thinks in words. Much more than one thinks, one thinks in words. And many people, when they ask for an explanation of this or that, are content to be told some word which has a sound familiar to them, which reminds them of this or that; and then they take what they feel at such a word for an explanation and believe they then have the thought. | |||

Yes, what I have just said has, at a certain time in the development of human intellectual life, led to the emergence of a view which is still shared today by many people who call themselves thinkers. In the new edition of my "Welt- und Lebensanschauungen im neunzehnten Jahrhundert" (World and Life Views in the Nineteenth Century), I have attempted to thoroughly reshape this book by sending a history of the development of Western thought in advance, beginning with the sixth century before Christ up to the nineteenth century, and by then adding at the end to what was given when the book first appeared an account of, let us say, intellectual life up to our own day. The content, which was already there, has also been altered many times. There I had to show how thought actually first comes into being in a certain age. It really only emerged, one could say, around the 6th or 8th century before Christ. Before that, human souls did not experience what can be called thoughts in the proper sense of the word. What did human souls experience before that? They experienced images. And all experience of the outer world took place in images. From certain points of view I have often said this. This image-experience is the last phase of the old clairvoyant experience. Then, for the human soul, the image passes into the thought. | |||

What I have intended in this book is to show this result of spiritual science purely by following the philosophical development. Remaining entirely on the ground of philosophical science, it is shown that the thought was once born in ancient Greece, that it arises from the fact that it springs forth for the human soul experience from the old symbolic experience of the outer world. Then I tried to show how this thought continues in Socrates, in Plato, Aristotle, how it takes on certain forms, how it develops further and then in the Middle Ages leads to what I now want to mention. | |||

The development of the thought of whether there can be anything at all in the world that is called general thoughts, general concepts, leads to the so-called nominalism, to the philosophical view that the general concepts can only be names, that is, only words. So for this general thought there was even the philosophical view, and many still have it today, that these general thoughts can only be words. | |||

In order to clarify what has just been said, let us take an easily comprehensible and general concept; let us take the concept "triangle" as a general concept. The one who comes with his point of view of nominalism, who cannot get away from what has developed as nominalism in this respect in the time of the 11th to 13th century, says something like this: Draw me a triangle! - Well, I will draw him a triangle, for example, like this: | |||

[[File:GA151 012.gif|center|150px|Drawing from GA 151, p. 12]] | |||

Fine, he says, that's a special triangle with three acute angles, there is such a thing. But I will draw you another one. - And he draws a triangle that has a right angle and one that has a so-called obtuse angle. | |||

[[File:GA151 013.gif|center|400px|Drawing from GA 151, p. 13]] | |||

So, now we call the first an acute triangle, the second a right triangle and the third an obtuse triangle. Then the person says: I believe you, there is an acute triangle, a right triangle and an obtuse triangle. But all that is not the triangle. The general triangle must contain everything that a triangle can contain. Under the general idea of the triangle must fall the first, the second and the third triangle. But a triangle that is acute-angled cannot at the same time be right-angled and obtuse-angled. A triangle that is acute-angled is a special triangle, not a general triangle; likewise a right-angled and an obtuse-angled triangle is a special triangle. But a general triangle cannot exist. So the general triangle is a word that sums up the special triangles. But the general concept of triangle does not exist. It's a word that sums up the particulars. | |||

Of course, this goes further. Let us suppose that someone pronounces the word lion. Now he who stands on the standpoint of nominalism says: There is a lion in the Berlin Tiergarten, there is also a lion in the Hanover Tiergarten, there is also one in the Munich Tiergarten. The individual lions exist; but a general lion, which should have something to do with the Berlin, Hanoverian and Munich lions, does not exist. That is a mere word that sums up the individual lions. There are only individual things, and apart from the individual things, the nominalist says, there is nothing but words that sum up the individual things. | |||

This view, as I said, has emerged; it is still held today by astute logicians. And anyone who thinks about the matter that has just been discussed will basically have to admit to himself: There is something special about it; I cannot easily come to the conclusion whether there really is this "lion in general" and the "triangle in general", for I do not quite see it. If someone were to come along and say: "Look, dear friend, I can't allow you to show me the Munich, the Hanoverian or the Berlin lion. If you claim that the lion exists "in general", you must lead me somewhere where the "lion exists in general". But if you show me the Munich, the Hanoverian and the Berlin lion, you have not proved to me that the "lion in general" exists. - If someone came who had this view and you were to show him the "lion in general", you would at first be somewhat embarrassed. It is not so easy to answer the question of where to lead the person to whom one should show the "lion in general". | |||

Well, we don't want to go now to what spiritual science gives us; that will come. For once we want to remain with thinking, we want to remain with what can be achieved through thinking, and we will have to say to ourselves: If we want to remain on this ground, it is not right that we should lead any doubter to the "lion in general". That is really not possible. Here lies one of the difficulties which one must simply admit. For if one does not want to admit this difficulty in the field of ordinary thought, then one does not enter into the difficulty of human thought in general. | |||

Let us remain with the triangle; for after all, it is indifferent to the general matter whether we make the matter clear to ourselves by means of the triangle, the lion, or something else. First of all, it seems hopeless that we should draw a general triangle that contains all qualities, all triangles. And because it not only seems hopeless, but is hopeless for ordinary human thinking, all external philosophy stands at a borderline here, and its task would be to really admit to itself for once that as external philosophy it stands at a borderline. But this borderline is only that of external philosophy. But there is a possibility of crossing this dividing line, and we now want to acquaint ourselves with this possibility. | |||

Let us think that we do not simply draw the triangle in such a way that we say: Now I have drawn you a triangle, and there it is. - There will always be an objection: This is an acute triangle, it is not a general triangle. You can draw the triangle in a different way. Actually, you can't; but we will see in a moment how this ability and inability relate to each other. Let us assume that we draw the triangle we have here in this way and allow each individual side to move in any direction it wishes. And let us allow it to move at different speeds. (Speaking on the blackboard drawing): | |||

[[File:GA151 015.gif|center|300px|Drawing from GA 151, p. 15]] | |||

This side moves so that the next moment it takes this position, this one so that the next moment it takes this position. This one moves much slower, this one moves faster and so on. Now the direction is reversed. | |||

In short, we enter into the uncomfortable idea that we say: I don't just want to draw a triangle and leave it like that, but I make certain demands on your imagination. You must imagine that the sides of the triangle are constantly in motion. If they are in motion, then a right-angled or an obtuse-angled triangle or any other can emerge simultaneously from the form of the motions. Two things can be done and demanded in this field. The first thing one can demand is that one be comfortable. If someone draws you a triangle, then it is finished and you know what it looks like; now you can rest comfortably in your thoughts, for you have what you want. But you can also do the other thing: Consider the triangle as a starting point, so to speak, and allow each side to turn at different speeds and in different directions. In this case, however, one does not have it so comfortable, but one must carry out movements in one's thoughts. But for this one really has the general thought triangle in it; it is only not to be attained if one wants to conclude at a triangle. The general thought triangle is there when one has the thought in continual movement, when it is versatile. | |||

Because the philosophers have not done what I have just said, to set thought in motion, they necessarily stand at a borderline and establish nominalism. Now let us translate what I have just said into a language we know, a language we have known for a long time. | |||

What is demanded of us, if we are to ascend from the special thought to the general thought, is that we set the special thought in motion, so that the thought in motion is the general thought which slips from one form into another. Form, I say; rightly thought, is: the whole moves, and each individual thing that comes out of it through the movement is a form complete in itself. In the past I only drew individual shapes, an acute-angled triangle, a right-angled triangle and an obtuse-angled triangle. Now I draw something - I don't actually draw it, I've already said that, but you can imagine it - which is supposed to evoke the idea that the general thought is in motion and generates the individual form by standing still - "generates the form", I say. | |||

There we see that the philosophers of nominalism, who necessarily stand at a borderline, move in a certain realm, in the realm of the spirits of form. Within the realm of the spirits of form, which is all around us, the forms reign; and because the forms reign, there are individual, strictly self-contained things in this realm. From this you see that the philosophers I mean have never made up their minds to go out of the realm of forms, and therefore can have nothing in general thought but words, properly mere words. If they were to go out of the realm of special things, that is, of forms, they would enter into a conception that is in perpetual movement, that is, they would have in their thinking a realisation of the realm of the Spirits of Motion, the next higher Hierarchy. But most philosophers do not allow themselves to do this. And when once, in the last period of occidental thought, someone did allow himself to think in this sense, he was little understood, although he is much spoken of and talked about. Look up what Goethe wrote in his "Metamorphosis of Plants", what he called the " archetypal plant"; then look up what he called the "archetypal animal", and you will find that you can only come to terms with these terms "archetypal plant", "archetypal animal" if you think of them in a mobile way. If one takes up this mobility of which Goethe himself speaks, then one does not have a closed concept, limited in its forms, but one has what lives in its forms, what creeps through in the whole development of the animal kingdom or the plant kingdom, which changes in this crawling through just as the triangle changes into an acute-angled or an obtuse-angled one, and which can be "wolf" and "lion", or "beetle", depending on how the mobility is arranged in such a way that the qualities change in the passage through the details. Goethe set the rigid concepts of forms in motion. That was his great, central deed. That was the significant thing he introduced into the view of nature of his time. You see here by means of an example how what we call spiritual science is actually suited to lead people out of what they must necessarily cling to today, even if they are philosophers. For without concepts gained through spiritual science it is not at all possible, if one is honest, to admit anything other than that the general thoughts are mere words. That is the reason why I said: Most people have only no thoughts. And if you speak to them of thoughts, they reject it. | |||

When does one speak of thoughts to people? For example, when one says that animals and plants have group souls. Whether one says general thoughts or group souls - we shall see in the course of the lectures what the relationship is between the two - it comes to the same thing for thinking. But the group soul cannot be understood in any other way than by thinking of it in movement, in continual outer and inner movement; otherwise one does not arrive at the group soul. But people reject this. That is why they also reject the group soul, reject the general thought. | |||

But to get to know the revealed world one does not need thoughts; one only needs the memory of what one has seen in the realm of form. And that is what most people only know: what they have seen in the realm of form. Then the general thoughts remain mere words. Therefore I could say: Most people have no thoughts. For general thoughts remain mere words for most people. And if among the various spirits of the higher Hierarchies there were not also the genius of language which forms the general words for the general concepts, men themselves would not do so. So it is from language that men first get their general thoughts, and they have not much else than the general thoughts preserved in language. | |||

But from this we see that there must be something peculiar about the thinking of real thoughts. That there must be something quite peculiar about it, we can understand from the fact that we see how difficult it actually is for people to come to clarity in the field of thought. So in the outer trivial life one will perhaps often claim, if one wants to be a little prestigious, that thinking is easy. But it is not easy. For real thinking always requires a very close, in a certain sense unconscious, being touched by a breath from the realm of the spirits of movement. If thinking were so easy, there would not be such colossal blunders in the field of thought, and one would not be troubled for so long with all kinds of problems and errors. Thus, for more than a century, we have been plagued with an idea that I have already mentioned several times and that Kant expressed. | |||

Kant wanted to eliminate the so-called ontological proof of God. This ontological proof of God also comes from the time of nominalism, where it was said that there were only words for the general concepts and that there was not something general that would correspond to the individual thoughts as the individual thoughts do to the ideas. I will cite this ontological proof of God as an example of how thinking is done. | |||

He says approximately: If one accepts a God, then he must be the most perfect being. If he is the most perfect being, then he must not lack being, existence; for otherwise there would be an even more perfect being, which would have those qualities which one thinks, and which would also exist. Therefore one must think the most perfect being in such a way that it exists. Thus one cannot think of God as existing in any other way than by thinking of him as the most perfect being. That is to say, one can deduce from the concept itself that, according to the ontological proof of God, God must exist. | |||

Kant wanted to refute this proof by trying to show that one cannot prove the existence of a thing at all from a concept. He coined the famous word for this, which I have also alluded to several times: A hundred real thalers are no more and no less than a hundred possible thalers. This means that if a thaler has three hundred pennies, one must calculate one hundred real thalers at three hundred pennies each, and likewise one must calculate one hundred possible thalers at three hundred pennies each. Thus a hundred possible thalers contain as much as a hundred real thalers; that is, there is no difference whether I think of a hundred real or a hundred possible thalers. Therefore one must not peel existence out of the mere thought of the most perfect being, because the mere thought of a possible God would have the same properties as the thought of a real God. | |||

That seems very reasonable. And for a century people have been plaguing themselves about how it is with the hundred possible talers and the hundred real talers. But let us take an obvious point of view, namely that of practical life. From this point of view, can we say that a hundred real thalers do not contain more than a hundred possible ones? One can say that a hundred real thalers contain just a hundred thalers more than a hundred possible thalers! It is quite clear that there is a difference between a hundred possible thalers on the one hand and a hundred real ones on the other. On the other side there are just a hundred more thalers. And it seems that in most cases of life it is the hundred real thalers that count. | |||

But the matter also has a deeper aspect. One can ask the question: What is the difference between a hundred possible talents and a hundred real talents? I think everyone will admit that: For the one who can have the hundred thalers, there is undoubtedly a great difference between a hundred possible and a hundred real thalers. For think of it, you need a hundred thalers, and someone gives you the choice of giving you a hundred possible thalers or a hundred real thalers. If you can have them, the difference seems to matter after all. But suppose you were in the case where you really could not have the hundred thalers; then it might be that it is highly indifferent to you whether someone does not give you a hundred possible or a hundred real thalers. If you cannot have them, then indeed a hundred real and a hundred possible thalers contain quite the same amount. | |||

That does have a meaning. It means that the way Kant spoke about God could only be spoken of at a time when God could no longer be had through human experience of the soul. When he was not attainable as a reality, the concept of a possible God or a real God was just as indifferent as it is indifferent whether one cannot have a hundred real thalers or a hundred possible thalers. If there is no way for the soul to reach the real God, then certainly no development of thought in the style of Kant will lead to it. | |||

There you see that there is a deeper side to the matter. But I only mention it because I wanted to make it clear that when the question of thinking arises, one must dig a little deeper. For errors of thought creep through the most enlightened minds, and for a long time one does not see where the fragility of such a thought actually lies, such as, for example, the Kantian thought of the hundred possible and the hundred real talers. In the case of thought, it is always important to take into account the situation in which the thought is conceived. | |||

From the nature of the general thought first and then from the existence of such an error of thought as the Kantian one in particular, I have tried to show you that the ways of thinking cannot nevertheless be considered so completely without delving into things. I still want to approach the matter from a third side. | |||

[[File:GA151 022.gif|center|500px|Drawing from GA 151, p. 22]] | |||

Let us assume that here is a mountain or a hill (see drawing, right) and here is a steep slope (drawing, left). On this rugged slope there is a spring; the spring falls vertically down the slope like a real waterfall. Under the same conditions as there, there is also a spring on the other side. It wants the same thing as the first, but it does not do it. It cannot fall down as a waterfall, but runs down quite nicely in the form of a stream or river. - Does the water have different powers in the second spring than in the first? Obviously not. For the second spring would do quite the same as the first, if the mountain did not hinder it and send up its forces. If the forces that the mountain sends up, the holding forces, are not present, it will fall down like the first spring. So two forces come into consideration: the holding force of the mountain and the force of gravity of the earth, by virtue of which the one source falls down. But this is just as present with the other spring, for one can say: It is there, I see how it pulls the spring down. If someone were a sceptic, he could deny this in the case of the second source and say: At first you see nothing there, while in the case of the first source every drop of water is pulled down. So in the case of the second source, one must add at every point the force that counteracts gravity, the holding force of the mountain. | |||

Now suppose someone came and said: 'I don't really believe what you're telling me about gravity, and I don't believe what you're telling me about your holding power either. Is the mountain there the cause of the spring taking that path? I do not believe it. - Now you could ask him: What do you believe then? - He could answer: I believe that there is some water down there, and there is also some water above it, and above it again, and so on. I believe that the water which is below is pushed down by the water above, and this upper water is pushed down by that above it. Each section of water above it always pushes down the one in front. - This is a considerable difference. The first person claims: Gravity pulls down the masses of water. The second, on the other hand, says: These are batches of water, they always push down the ones below them, and as a result the water above then goes behind. | |||

Not true, it would be quite silly for a person to speak of such a shifting. But let us assume that we are not dealing with a stream or a river, but with the history of mankind, and that such a last-characterised person would say: The only thing I believe in you is this: Now we are living in the 20th century, certain events have taken place; these are caused by those in the last third of the 19th century; these latter are again caused by those in the second third of the 19th century and these again by those from the first third. - This is called a pragmatic conception of history, where one speaks of causes and effects in the sense that one always explains the following events from the preceding events in question. Just as someone can deny gravity and say that there is always someone pushing in the water sections, so it is when someone does pragmatic history and explains the state of affairs in the 19th century as a consequence of the French Revolution. We, of course, say: No, there are other forces besides those who are pushing back there, which are not even present in the right sense. For just as those forces do not push the mountain stream behind, neither do the events in the history of mankind behind them push; but new influences are always coming from the spiritual world, just as gravity is always at work at the source; and they cross with other forces, just as gravity crosses with the holding power of the mountain in the case of the stream. If only the one force were present, you would see that history proceeds quite differently. But you do not see the individual forces in it. You do not see that which is the physical development of the world, which has been described as the result of the development of Saturn, the Sun, the Moon and the Earth; and you do not see that which continually happens to the human souls who live through the spiritual world and come down again, that which again and again enters into this development from the spiritual worlds. You simply deny that. | |||

But we have such a conception of history, which looks as if someone were to come with such views as have just been characterised, and it is not so particularly rare. In the 19th century it was even regarded as tremendously witty. But what would we be able to say about it from the point of view we have just gained? If someone were to claim the same thing about the mountain stream as about history, he would be claiming absolute nonsense. But what is there in the matter that he asserts the same nonsense in regard to history? - History is so complicated that one does not notice that it is presented almost everywhere as pragmatic history; one just does not notice it. | |||

We see from this that spiritual science, which has to gain sound principles for the conception of life, has something to do in the manifold fields of life; that there is indeed a certain necessity of first learning to think, of first acquainting oneself with the inner laws and impulses of thought. Otherwise all sorts of grotesque things can happen. For example, someone is stumbling, stumbling, limping along on the problem of thinking and language today. This is the famous language critic Fritz Mauthner, who has now also written a large philosophical dictionary. Mauthner's thick "Critique of Language" has now gone into its second edition; it has thus become a famous book for our contemporaries. This book contains much that is intellectually rich, but also terrible things. For example, one can find in it the curious error of thought - and one stumbles over such an error of thought after almost every fifth line - that the good Mauthner doubts the usefulness of logic. For him, thinking is only speaking, and then there is no point in doing logic, then one is only doing grammar. But moreover, he says: "Since logic cannot rightly exist, logicians are all fools. Fine. And then he says: In ordinary life, after all, conclusions give rise to judgements and judgements give rise to ideas. That's how people do it. What do we need logic for, then, if people do it in such a way that they turn conclusions into judgements and judgements into ideas? What do we need a logic for? - This is just as witty as if someone said: Why do we need botany? Plants were still growing last year and two years ago! - But such logic is found in those who frown upon logic. It is understandable that he should frown upon it. One finds much stranger things in this strange book, which, with regard to the relationship between thought and speech, comes not to clarity but to confusion. | |||

I said that we need a substructure for the things that are to lead us, however, to the heights of spiritual contemplation. A substructure of the kind that has been developed today may seem somewhat abstract to some, but we will need it. And I think I am trying to make things so simple that it will be clear what is important. I would particularly like to emphasise that even through such simple observations one can get an idea of where the boundary lies between the realm of the spirits of form and the realm of the spirits of movement. But the fact that one gets such a concept is intimately connected with whether one may admit general thoughts at all, or whether one may admit only ideas or concepts of individual things. I say expressly: may admit.|151|9ff}} | |||

== Imaginative thinking == | |||

Pure thinking is the preliminary stage to [[spiritual perception]], to [[imagination]]. In pure thinking we first experience the [[thought beings]], but we do not yet see them. In order for them to illuminate themselves into an imaginative image, our thinking activity must be reflected in the [[light ether]]. And before these [[elementary beings]], created by us but becoming independent, detach themselves from our [[will]], we first see ourselves, i.e. actually our [[astral body]] in its true form, shaped by the [[etheric body]] and illuminated by the light ether: this is the encounter with the [[lesser guardian of the threshold]], who first appears to us in his frightening [[dragon]] form. Only then does the spiritual gaze become free for further spiritual vision - at least this is how it should be with a healthy spiritual development. | |||

{{GZ|This thinking, that we ... ... as our mere property, for not only is there the proverb that thoughts are duty-free, by which it is meant to be implied that thoughts really only have meaning for our individual, but there is also the awareness in the widest circles that everyone with his thinking is only carrying out an inner process, that this thinking more or less only has a meaning for himself. But the reality is quite different. This thinking is actually a process of our etheric body. And of what actually happens in thinking, man knows the very least. The human being accompanies the very least of what happens in his thinking with his consciousness. In thinking, man knows some of what he thinks. But infinitely more is unfolded as accompanying thinking already in daily thinking. And in addition to this, we continue to think at night, when we sleep. It is not true that thinking stops when we fall asleep and starts again when we wake up. Thinking continues. And among the various dream processes, processes of the dream life, there are also these, that when a person wakes up, his I and astral body submerge into his etheric body and physical body. There he submerges and enters into a tangle, into a weaving life, of which, if he only watches a little, he can know: these are weaving thoughts, there I submerge as into a sea that consists only of weaving thoughts. Many a person has said to himself when he wakes up: If only I could remember what I was thinking, that was something very clever, that would help me enormously if I could remember it now! That is not a mistake. There is really something like a surging sea down there; that is the surging, weaving, ethereal world, which is not merely a somewhat thinner matter, as English theosophy likes to portray it, but is the weaving world of thought itself, is really spiritual. One is immersed in a weaving world of thought. | |||

What we are as human beings is really much cleverer than what we are as conscious human beings. There is nothing left but to confess it. It would also be sad if we were not unconsciously cleverer than we are consciously, for otherwise we could do nothing but repeat ourselves at the same level of cleverness in every life. But we are indeed already carrying with us in the present life what we can become in the next life; for that will be the fruit. And if we were really always able to catch what we are immersed in, we would catch much of what we will be in the next life. So down there it surges and weaves; there is the germ for our next embodiment, and we take that into ourselves. Hence the prophetic nature of the dream life. Thinking is something tremendously complicated, and only a part of what goes on in thinking does man take into his consciousness. For what goes on in thought is a process of time. By perceiving with an alert mind, we are at the same time cosmic human beings. Our process of seeing brings about luminescence, so we are cosmic space people. Through that which takes place in thinking, we are cosmic time-people, and everything that happened before our birth, what happens after our death, and so on, has a part in it. Thus we participate through our thinking in the whole cosmic process of time, through our sense perception in the whole cosmic process of space. And only the earthly process of sense perception is for ourselves.... | |||

As soon as we strip thinking off the abstractness which it has for our consciousness, and submerge ourselves in that sea of the weaving world of thought, we come to the necessity of not only having such abstract thoughts in it as earthly man does, but of having images in it. For everything is created from images, images are the true causes of things, images lie behind everything that surrounds us, and it is into these images that we dive when we dive into the sea of thought. Plato meant these images, all those who spoke of spiritual archetypal causes meant these images, Goethe meant these images when he spoke of his archetypal plant. These images are found in imaginative thinking. But this imaginative thinking is a reality, and we immerse ourselves in it when we immerse ourselves in the surging thinking that moves along in the stream of time.|157|296f}} | |||

[[File:Pauli.jpg|thumb|[[w:Wolfgang Pauli|Wolfgang Pauli]] (1945)]] | |||

Without having any knowledge of the spiritual sciences himself, the Austrian quantum physicist [[w:Wolfgang Pauli|Wolfgang Pauli]] (1900 - 1958) came to a similar account from his personal experiences, which he was able to bring to clear consciousness in many conversations and his extensive correspondence with [[w:C. G. Jung|C. G. Jung]]: | |||

{{LZ|If one analyses the preconscious stage of concepts, one always finds ideas consisting of "symbolic" images with generally strong emotional content. The preliminary stage of thinking is a painting seeing of these inner images, the origin of which cannot generally and primarily be attributed to sense perceptions ... ... | |||

But the archaic attitude is also the necessary precondition and the source of the scientific attitude. To a complete cognition belongs also that of the images from which the rational concepts have grown... The ordering and regulating must be placed beyond the distinction of "physical" and "psychic" - just as Plato's "ideas" have something of concepts and also something of "natural forces" (they produce effects of themselves). I am very much in favour of calling this "0ordering and regulating" "archetypes"; but it would then be inadmissible to define these as psychic contents. Rather, the inner images mentioned ("dominants of the collective unconscious" according to Jung) are the psychic manifestation of the archetypes, which, however, would also have to produce, generate, condition all natural laws in the behaviour of the body world. The natural laws of the physical world would then be the physical manifestation of the archetypes... Every law of nature should then have a counterpart inside and vice versa, even if this cannot always be seen directly today.|The Pauli Jung Dialogue, p. 219}} | |||

[[Rudolf Steiner]] characterises the essence of these [[archetype]]s thus: | |||

{{GZ|Above all, it must be emphasised that this world is woven out of the material (even the word 'material' is of course used here in a very inauthentic sense) of which human thought consists. But as thought lives in man, it is only a shadow image, a shadow of his real being. Just as the shadow of an object on a wall relates to the real object that casts this shadow, so the thought that appears through the human head relates to the entity in the "spirit land" that corresponds to this thought. Now, when man's spiritual sense is awakened, he really perceives this thought being, just as the sensual eye perceives a table or a chair. He walks in an environment of thought beings. The sensual eye perceives the lion and the sensual mind perceives only the thought of the lion as a shadow, as a shadowy image. The spiritual eye sees the thought of the lion in the "spirit land" as really as the sensual eye sees the physical lion. Again, we can refer to the parable already used with regard to the "soul land". Just as to the blind man who has had an operation his surroundings suddenly appear with the new qualities of colours and lights, so to him who learns to use his spiritual eye the surroundings appear filled with a new world, with the world of living thoughts or spiritual beings. - In this world the spiritual archetypes of all things and beings can be seen, which are present in the physical and in the spiritual world. Think of a painter's picture as existing in the spirit before it is painted. Then we have a simile of what is meant by the expression archetype. It is not important here that the painter may not have such an archetype in his mind before he paints; that it only gradually comes into being completely during the practical work. In the real "world of the spirit" such archetypes exist for all things, and physical things and entities are after-images of these archetypes. - If he who trusts only his outer senses denies this archetypal world and asserts that the archetypes are only abstractions which the comparative intellect obtains from sensuous things, this is understandable; for such a one cannot perceive in this higher world; he knows the world of thought only in its shadowy abstractness. He does not know that the spiritual observer is as familiar with the spiritual beings as he himself is with his dog or his cat, and that the world of archetypes has a far more intense reality than the sensuous-physical one. | |||

However, the first insight into this "spirit land" is even more confusing than the one into the soul world. For the archetypal images in their true form are very dissimilar to their sensual after-images. But they are just as dissimilar to their shadows, the abstract thoughts. - In the spiritual world everything is in perpetual motion, in ceaseless creation. There is no rest, no staying in one place, as there is in the physical world. For the archetypes are creative beings. They are the masters of all that comes into being in the physical and spiritual world. Their forms are rapidly changing; and in every archetype lies the possibility of assuming innumerable special forms. They let the special forms sprout from themselves, as it were; and no sooner is one produced than the archetype prepares to let another spring from itself. And the archetypes are more or less related to each other. They do not work in isolation. One needs the help of the other to create. Innumerable archetypes often work together in order that this or that entity may come into being in the spiritual or physical world.|9|54f}} | |||

[[Immanuel Kant]] considered such an ''intellectus archetypus'', capable of direct contemplation of the archetypes, to be possible in principle, but believed that man could never rise to it. Goethe thought differently: | |||

{{LZ|When I sought to make use of Kant's teaching, if not to penetrate it, it sometimes seemed to me that the delicious man was proceeding in a mischievously ironic manner, in that he seemed at times to be endeavouring to restrict the faculty of knowledge in the narrowest possible way, and at other times to be pointing beyond the limits he himself had drawn with a sideways glance. He might have noticed, of course, how presumptuously and foolishly man proceeds when, comfortably equipped with little experience, he immediately and rashly denies and tries to establish something, a cricket that runs through his brain, to cancel out the objects. That is why our master restricts his thinker to a reflective discursive power of judgement, forbids him a determining one altogether. Then, however, after he has driven us sufficiently into a corner, even to despair, he decides on the most liberal expressions and leaves it to us to decide what use we want to make of the freedom that he to some extent allows. In this sense the following passage was most significant to me: | |||

:"We can think of an intellect which, because it is not discursive like ours, but intuitive, goes from the synthetic general, the conception of a whole as such, to the particular, that is, from the whole to the parts: Here it is not at all necessary to prove that such an intellectus archetypus is possible, but only that in the opposition of our discursive intellect, which is in need of images (intellectus ectypus), and the accidental nature of such a condition, we are led to that idea of an intellectus archetypus, which also contains no contradiction." | |||

::- Immanuel Kant: Critique of Judgment, [http://www.zeno.org/Philosophie/M/Kant,+Immanuel/Kritik+der+Urteilskraft/Zweiter+Teil.+Kritik+der+teleologischen+Urteilskraft/Zweite+Abteilung.+Dialektik+der+teleologischen+Urteilskraft/%C2%A7+77.+Von+der+Eigent%C3%BCmlichkeit+des+menschlichen+Verstandes,+wodurch+uns+der+Begriff+eines+Naturzwecks+m%C3%B6glich+wird § 77] | |||

It is true that the author seems here to be pointing to a divine intellect, but if in the moral, through faith in God, virtue and immortality, we are to raise ourselves into an upper region and approach the first being: so it might well be the same case in the intellectual that, by beholding an ever-creating nature, we made ourselves worthy of spiritual participation in its productions. After all, if I had first unconsciously and out of an inner urge restlessly pressed on to that archetypal, typical thing, if I had even succeeded in building up a representation in keeping with nature, then nothing could now prevent me from courageously passing through the adventure of reason, as the old man from Königsberg himself calls it.|Goethe, p. 91}} | |||

However, Rudolf Steiner also made it clear that this kind of imaginative thinking, the spiritual perception of the archetypes, had to take a back seat for a time so that man could rise to independent thinking in the abstract imageless intellect. The remnants of the old clairvoyance, which still lingered in the Platonic vision of ideas, first had to fade away: | |||

{{GZ|The old times still had remnants of the old clairvoyance, through which in ancient times people looked into the spiritual world, where they really saw how man does when he is outside the physical and etheric body with his I and astral body and outside in the cosmos. Man would never have attained full freedom and individuality if he had remained with the old clairvoyance. Man had to lose the old clairvoyance; he had to take possession, as it were, of his physical self. The thinking he would develop if he were to see the whole mass under his consciousness, which is there as thinking, feeling, willing, would be heavenly thinking, but not independent thinking. How does man come to this independent thinking? Well, think of yourself as sleeping at night, lying in bed. That is to say, the physical body and etheric body lie in bed. Now, when you wake up, the I and the astral body come in from outside. There is further thought in the etheric body. Now the I and the astral body submerge, they first take hold of the etheric body. But it does not last long, for at this moment the thought may flash up: What was I thinking, what was that clever thing? But the human being has the desire to grasp the physical body as well, and at this moment all this disappears; now the human being is completely in the sphere of earthly life. Hence it is that man immediately seizes the earthly body, that he cannot bring to consciousness the subtle swirl of etheric thought. In order to be able to develop the consciousness "it is I who think", man must seize his earthly body as an instrument, otherwise he would not have the consciousness "it is I who think", but "it is the angel protecting me who thinks". This consciousness "I think" is only possible through the grasping of the earthly body. That is why it is necessary that in earthly life man is enabled to use his earthly body. In the time to come he will have to take hold of this earthly body more and more through what the earth gives him. His justified egoism will become greater and greater. This must be counterbalanced by gaining the knowledge that spiritual science gives. We are at the starting point of this time.|157|300f}} | |||

Today the time is ripe to regain imaginative thinking, which withered away with the Platonic vision of ideas, on a new, higher level with fully developed self-awareness. | |||

== Experienced thoughts and the imagination of the bone system == | |||

{{GZ|My "Philosophy of Freedom" has been little understood because people have not understood how to read it. They have read it as one reads another book, but my "Philosophy of Freedom" is not meant to be read as other books are. My "Philosophy of Freedom" lives first in thoughts, but in properly experienced thoughts. Non-experienced thoughts, abstract, logical thoughts, such as one has today in science in general, these are experienced in the brain. Such thoughts as I have expressed in my "Philosophy of Freedom" - now comes the paradox - are experienced as a whole human being in his bone system. Correctly, as a whole human being in his bone system. And I would like to say the even more paradoxical thing - this of course happened, only you didn't notice it because you didn't connect it with it -: when people understood my "Philosophy of Freedom", they dreamed of skeletons several times in the course of reading it, and especially when they had finished. This is morally connected with the whole position of the "Philosophy of Freedom" in relation to the freedom of the world. Freedom consists already in the fact that from the bones one moves the muscles of the human being in the outer far. The unfree follows his drives and instincts. The free man is guided by the demands and requirements of the world, which he must first love. He must gain a relationship to this world. This is expressed in the imagination of the bone system. Inwardly, the bone system is that which experiences thoughts. So one experiences thoughts with the bone system, with the whole human being, especially with the whole human being who is actually earthbound. There have been people who wanted to paint pictures from my books; they showed me all kinds of things. They wanted to present the thoughts of the "Philosophy of Freedom" in picture form. If you want to paint its content in this way, you have to perform dramatic scenes, which are performed by human skeletons. Just as freedom itself is something in which one must get rid of everything that is merely instinctive, so that which man experiences by having the thoughts of freedom is something in which he must get rid of his flesh and blood. He must become skeletal, must become earthy, thoughts must become really earthy.|316|113f}} | |||

== Literature == | == Literature == | ||

Latest revision as of 05:15, 21 March 2022

Pure thinking (Latin: intellectus purus) is creative, active, living thinking and thus at the same time pure will, i.e. pure spiritual activity. It is the beginning of direct spiritual experience. Its content are at first pure concepts without direct reference to sensual perceptions and the reciprocal lawful relationships to each other resulting from the concepts themselves, which reveal themselves holistically in pure forms and structures free of sensuality. Pure thinking thus differs from the usual discursive activity of understanding, through which we try to penetrate sensual experiences by thinking and combine ready-made concepts with one another according to logical criteria or formally derive them from one another through logical conclusions. We use the physical brain as a tool in the activity of understanding. Although it is not the brain that thinks, the brain reflects our own mental activity back to us in the form of intellectual thoughts and only thereby brings them to our consciousness. Through the unprejudiced mind we can, as Rudolf Steiner has repeatedly emphasised, grasp spiritual content in principle, but we cannot experience it directly. This only becomes possible through pure, sensuality-free thinking, which presupposes bodiless experience and is thus at the same time body-free thinking[1], through which the spirit self is already formed as the higher spiritual element of the human being (Lit.:GA 53, p. 214f).

Pure thinking is pure will

„When I speak of pure thinking in my "Philosophy of Freedom", this designation was already out of place for the cultural conditions of the time; for Eduard von Hartmann once said to me: "There is no such thing; one can only think on the basis of external perception!" I could only answer him: "You have to try it; then you will learn it and in the end you will really be able to do it. - Suppose, then, that you could have thoughts in the pure flow of thought. Then the moment begins for you when you have led thinking to a point at which it no longer needs to be called thinking. In the twinkling of an eye - let us say in the twinkling of a thought - it has become something else. For this thinking, rightly called "pure thinking", has become pure will; it is willing through and through. If you have come so far in the soul that you have freed thinking from external perception, then it has at the same time become pure will. You float, if I may say so, with your soul in the pure course of thought. This pure course of thought is a course of will. With this, however, pure thinking, and even the effort after its exercise, begins to be not only an exercise of thought, but an exercise of will, and one that reaches into the centre of the human being. For you will make the strange observation: Only now can you speak of thinking, as one has it in ordinary life, as a head activity. Before, you had no right to speak of thinking as an activity of the head, for you only know this externally from physiology, anatomy and so on. But now you feel inwardly that you no longer think so high up, but that you begin to think with your chest. You are actually interweaving your thinking with the breathing process. In this way you are stimulating what the yoga exercises have artificially sought to do. You notice, as thinking becomes more and more an activity of the will, that it first wrings itself out of the human breast and then out of the whole human body. It is as if you were drawing this thinking out of the last cell fibre of your big toe. And if you study something like this with an inner sympathy, something that has entered the world with all its imperfections - I do not want to defend my "philosophy of freedom" - if you let something like this have its effect on you and feel what this pure thinking is, then you feel that a new inner human being has been born in you, who can bring about the development of will out of the spirit.“ (Lit.:GA 217, p. 148f)

Body-free thinking

„There are people who do not believe in the existence of such thoughts at all. They think that man cannot think anything that he does not draw from perception or from the bodily conditioned inner life. And all thoughts are only, so to speak, shadow images of perceptions or of inner experiences. He who asserts this only does so because he has never brought himself to the ability to experience with his soul the pure life of thought based in itself. But he who has experienced this has come to know that wherever thought is active in the life of the soul, to the extent that this thought permeates other processes of the soul, the human being is engaged in an activity in the creation of which his body is uninvolved. In the ordinary soul-life, thinking is almost always connected with other soul-activities: Perceiving, feeling, willing, etc., are almost always intermingled. These other processes come about through the body. But thinking plays a part in them. And to the extent that it plays a part, something goes on in the human being and through the human being in which the body is not involved. People who deny this cannot get beyond the deception which arises from the fact that they always observe the activity of thinking united with other activities. But in inner experience it is possible to rouse oneself mentally to experience the mental part of the inner life as separate from everything else. One can detach something from the scope of the soul's life that exists only in pure thoughts. In thoughts that exist in themselves, from which everything is eliminated that gives perception or bodily conditioned inner life. Such thoughts reveal themselves through themselves, through what they are, as a spiritual, a supersensible beingness. And the soul, which unites with such thoughts by excluding all perceiving, all remembering, all other inner life during this union, knows itself with thinking in a supersensible realm and experiences itself outside the body. For the one who sees through all this, the question can no longer come into consideration: is there an experience of the soul in a supersensible element outside the body? For him it would mean denying what he knows from experience. For him there is only the question: what prevents people from recognising such a certain fact? And to this question he finds the answer that the fact in question is one which does not reveal itself unless man first puts himself in such a state of soul that he can receive the revelation. At first people are suspicious when they themselves have to do something purely in their souls, so that something independent of them can be revealed to them. They believe because they have to prepare themselves to receive the revelation, they make the content of the revelation. They want experiences to which man does nothing, towards which he remains completely passive. If, moreover, such people are still unacquainted with the simplest requirements of scientific comprehension of a fact, then they see in soul-contents or soul-productions, in which the soul is depressed below the degree of conscious self-activation that is present in sense-perception and in arbitrary action, an objective revelation of a non-sensuous beingness. Such soul-contents are the visionary experiences, the mediumnistic revelations. - But what comes to light through such revelations is not supersensuous, it is a sub-sensuous world. The conscious waking life of the human being does not take place entirely in the body; above all, the most conscious part of this life takes place on the border between the body and the physical outer world; thus the life of perception, in which what takes place in the sense organs is just as much the carrying into the body of a process outside the body as a penetration of this process from the body; And so the life of the will, which is based on a placing of the human being into the world-being, so that what happens in the human being through his will is at the same time a member of the world-action. In this spiritual experience, which runs along the bodily border, the human being is to a great extent dependent on his bodily organisation; but mental activity plays a part in this experience, and to the extent that this is the case, the human being makes himself independent of the body in sense perception and volition. In visionary experience and in mediumistic production, man enters completely into dependence on the body. He switches off from his soul life that which makes him independent of the body in perception and volition. And thus soul contents and soul productions become mere revelations of the life of the body. Visionary experience and mediumistic production are the results of the fact that in this experience and production man is less independent of the body with his soul than in the ordinary life of perception and will. In the experience of the supersensible, which is meant in this writing, the development of the soul's experience goes in precisely the opposite direction to that of the visionary or mediumistic experience. The soul becomes progressively more independent of the body than it is in the life of perception and will. It attains that independence which can be grasped in the experience of pure thoughts, for a much broader soul activity.

For the supersensible activity of the soul meant here, it is extremely important to see through the experience of pure thinking with complete clarity. For basically this experience itself is already a supersensible activity of the soul. Only one through which one does not yet see anything supersensible. One lives with pure thought in the supersensible; but one experiences only this in a supersensible way; one does not yet experience anything else supersensible. And the supersensible experience must be a continuation of that soul-experience which can already be attained by uniting with pure thinking. That is why it is so important to be able to experience this union correctly. For from the understanding of this union shines the light which can also bring right insight into the nature of supersensible knowledge. As soon as the soul's experience would sink below the clarity of consciousness, which is expressed in thinking, it would be on an erroneous path for the true knowledge of the supersensible world. It would be grasped by the bodily processes; what it experiences and produces is then not revelation of the supersensible through it, but bodily revelation in the realm of the sub-sensible world.“ (Lit.:GA 10, p. 215ff)

Mathematics and pure thinking

Thinking in purely mathematical terms is already pure thinking:

„You will find numerous philosophers saying that there is no such thing as pure thinking, that all thinking must always be filled at least with remnants, however diluted, of sensual perception. One would have to believe, however, that such philosophers have never really studied mathematics, have never got involved in the difference between analytical mechanics and empirical mechanics, who assert such a thing. But our specialism has already brought us to the point where today we often philosophise without even a trace of knowledge of mathematical thinking. Basically, one cannot philosophise without at least having grasped the spirit of mathematical thinking.“ (Lit.:GA 322, p. 111f)

Ways to sensuality-free thinking

Meditation: The thought thinks the thought

„The most sensuality-free thoughts in the world are still the mathematical ones; but even when today's man thinks of a triangle, he thinks of it in terms of colour and a certain thickness, not abstract enough. But one comes nearer to supersensible thoughts when one pays attention to relations. To remember a tone is still the memory of something sensual; to remember a melody is already something that consists in a relationship of tones to one another, which as such does not belong to the sensual world. Or imagine a villain and next to him another - or even two good people - and one [villain] is an even greater villain than the other, or the one good is greater in good than the other: then in this relationship lies something that is not of the physical-sensuous world, something that leads us up into the spiritual world. If man thinks of a villain or sees one, it will touch him unpleasantly; but if he sees two villains side by side in a play, he will always like the worst villain better than the less bad one, because the great always attracts. The effect of various Shakespearean dramas, for example, is based on this. - That is why it is so important that we observe and study conditions in the outside world, because that leads us away from the sensual.

Another means of becoming free of sensuality [in thinking] is to make processes run in reverse, for example, reciting the Lord's Prayer backwards or the reverse review of our meditation.[2] Only in this way can man improve his memory. In the last four or five centuries memory has declined enormously, and it will do so much more in the future if people do not seize the opportunities now offered to improve it. The time is particularly favourable for these opportunities now, and later they will simply no longer be there. Memory will then become something other than just waiting to see if things want to come up for some dark reason. It will be like groping for the past, like sending out feelers, so to speak, that will reach for the past as if for something real. The time is particularly favourable now for this development and for esoteric development in general.

Thus it becomes apparent how our body is a Maja, thoughts of beings which are themselves again thoughts. The thought thinks the thought, that is a meditation sentence of the highest importance. Not our brain thinks, not our etheric or astral body, but thought itself thinks thoughts.“ (Lit.:GA 266b, p. 134ff)

Reason as the germinal beginning of a new clairvoyance

„No human being could actually come to real clairvoyance if he did not first have a tiny bit of clairvoyance in his soul. If it were true, which is a common belief, that men, as they are, are not clairvoyant, then they could not become clairvoyant at all. For just as the alchemist thinks that one must have a little gold in order to conjure up many quantities of gold, so one must necessarily be already somewhat clairvoyant, so that one can develop this clairvoyance further and further into the infinite.