Observation of Thinking

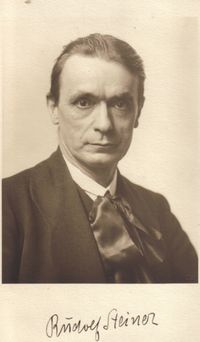

The observation of thinking, which Rudolf Steiner first discussed in detail in his "Philosophy of Freedom", is an important step on the path to conscious spiritual cognition. The thinking experience, the experience of thinking, usually eludes observation because the thinker, while thinking, directs his attention entirely to the object about which he is thinking. The conscious observation of thinking represents an exceptional state, which, however, every thinking person can deliberately bring about. He then observes his own spiritual activity - and thus stands at the beginning of spiritual perception in general, through which he experiences himself as a spiritual being. At the same time, however, this is also the starting point for all further spiritual perception.

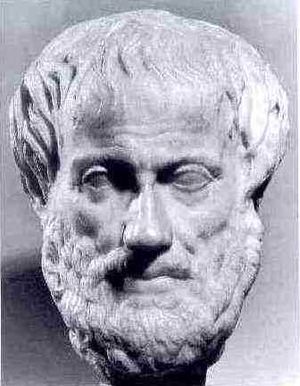

Aristotle and the "Thinking of Thinking"

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle already described the possibility of observing thinking as a "thinking of thinking":

„But thinking in itself has as its object that which is in itself most valuable, and the purest thinking also has the purest object. Consequently, thinking thinks itself; it participates in objectivity; it becomes itself the object by grasping and thinking, and thus thinking and its object become identical. For that which is receptive to the object and the pure being is the thinking spirit, and it realises its faculty by possessing the object.

The divine, therefore, which is ascribed to the thinking spirit as its property, is more this possession than mere receptivity; the most blessed and highest is pure contemplation. Now if God's blessedness is eternal, such as we shall ever have, how wonderful! If it is even higher, how much more wonderful! But this is how it is.

And the predicate of liveliness also belongs to it. For the efficacy of the thinking spirit is life; but God is pure efficacy, and his efficacy in and for itself is a supreme, an eternal life. And so then we say: God is the eternal, absolutely perfect living being, and to Him, therefore, belongs a timeless, eternal life and existence. This, then, is God's essence and concept.“ (Lit.: Aristotle, Metaphysics, Part II, VII.)

From "Thinking of Thinking" to the Concrete "Observation of Thinking"

What Rudolf Steiner described as "observation of thinking" in his "Philosophy of Freedom", however, goes far beyond "thinking of thinking" and leads to a concrete contemplation of thinking and of one's own spiritual being, which this brings forth, but in which the spiritual being of the world is also founded at the same time. The observation of thinking thus leads to a true self-knowledge, which is the necessary basis of the knowledge of the world.

„However, such observation of thought does not mean mere reflection on thinking, as is already found in Aristotle's "thinking of thinking" and in Descartes' cogito. Rather, it is about concrete perception and experience of what is thinking in thinking. If this is experienced perceptively, Steiner emphasises, then the human being recognises what he or she really is. He then also recognises what is felt in feeling and what is willed in willing, and only on the basis of this realisation does he then also understand the world around him and can live in it as a human being in a satisfying way.“ (Lit.: Clement, p. 6f)

„It is a question here, to indicate it only briefly, of the human being awakening to an inner life of thought what is otherwise merely combining thinking, as it underlies what is today often called 'science' alone. Then thinking is a life in thought. Then one can no longer think about thinking, but then it transforms itself into something else. Then thinking about thinking is transformed into a spiritual contemplation of thinking, then one has thinking before one as one otherwise has external sense objects before one, only that one has these before one's eyes and ears, while one has thinking before the soul filled with spiritual contemplation.“ (Lit.:GA 67, p. 82f)

Thinking, Feeling and Willing

„The difficulty of grasping thinking in its essence observationally lies in the fact that this essence all too easily slips away from the contemplating soul when the latter wants to bring it into the direction of its attention. Then all that remains for it is the dead abstract, the corpse of living thought. If one looks only at this abstract, one will easily find oneself urged towards it to enter into the "living" element of emotional mysticism, or even of the metaphysics of the will. One will find it strange when someone wants to grasp the essence of reality in "mere thoughts". But he who brings himself to have life truly in thought will come to the insight that the weaving in mere feelings or the looking at the will element cannot even be compared to the inner richness and the experience within this life, which is at rest in itself but at the same time moving in itself, let alone that the latter may be placed above the former. It is precisely from this richness, from this inner fullness of experience, that its counter-image in the ordinary attitude of the soul looks dead, abstract. No other human activity of the soul can be so easily misjudged as thinking.

Willing, feeling, they warm the human soul even in the after-living of its original state. It is all too easy for thinking to leave the soul cold in this after-experience; it seems to dry up the life of the soul. But this is only the strongly asserting shadow of its light-woven reality, warmly submerged in the world-appearances. This submersion takes place with a power flowing in the activity of thought itself, which is the power of love of a spiritual kind. One must not object that he who thus sees love in active thinking is transferring a feeling, love, into it. For this objection is in truth a confirmation of what is asserted here. For he who turns to essential thinking finds in it both feeling and will, the latter also in the depths of their reality; he who turns away from thinking and only to "mere" feeling and willing loses from these the true reality. He who wants to experience intuitively in thinking will also do justice to the emotional and volitional experience; but emotional mysticism and the metaphysics of the will cannot do justice to the intuitive-thinking penetration of existence. The latter will only too easily come to the conclusion that they stand in the real; the intuitive thinker, however, without feeling and alienated from reality, forms in "abstract thoughts" a shadowy, cold conception of the world.“ (Lit.:GA 4, p. 142ff)

The Observation of Thinking

If we want to know the world, we observe it and think about it. Rudolf Steiner understands observation as the "confrontation of thinking with the given" (Lit.:GA 3, p. 67), whereby it must be taken into account that the "given" initially appears in consciousness as a specific, intentionally grasped wholeness, which only thinking breaks down into individual, interrelated factors[1]. We actively produce thinking, but we do not observe it ourselves for the most part. In his "Philosophy of Freedom", Steiner described this observation of thinking, which we do not normally carry out, in great detail:

„Temporally, observation even precedes thinking. For we too must first come to know thinking through observation. It was essentially the description of an observation when we described at the beginning of this chapter how thinking is ignited by a process and goes beyond what is given without its intervention. Everything that enters into the circle of our experiences we first become aware of through observation. The content of sensations, perceptions, views, feelings, acts of will, dream and fantasy images, notions, concepts and ideas, all illusions and hallucinations are given to us through observation.

But thinking as an object of observation is essentially different from all other things. The observation of a table or a tree occurs to me as soon as these objects appear on the horizon of my experiences. But I do not observe thinking about these objects at the same time. I observe the table, I think about the table, but I do not observe it at the same moment. I must first place myself on a standpoint outside my own activity if I want to observe my thinking about the table in addition to the table. While observing objects and processes and thinking about them are quite everyday states that fill my ongoing life, observing thinking is a kind of exceptional state. This fact must be taken into account in an appropriate way when it comes to determining the relationship of thinking to all other observational contents. One must be clear that in the observation of thinking one applies to it a procedure which forms the normal state for the observation of all the other world-content, but which does not occur in the pursuit of this normal state for thinking itself.“ (Lit.:GA 4, p. 39f)

Thus, although we produce thinking by conceptually penetrating perception, we do not for the most part observe thinking itself in the process:

„This is the peculiar nature of thinking, that the thinker forgets thinking while he is doing it. It is not thinking that occupies him, but the object of thinking that he observes. So the first observation we make about thinking is that it is the unobserved element of our ordinary mental life.

The reason why we do not observe thinking in ordinary mental life is none other than that it is based on our own activity. What I do not bring forth myself enters my field of observation as a representational thing. I face it as something that has come about without me; it approaches me; I must accept it as the precondition of my thinking process. While I am thinking about the object, I am occupied with it, my gaze is turned towards it. This occupation is precisely the thinking contemplation. My attention is not directed to my activity, but to the object of this activity. In other words, while I am thinking, I am not looking at my thinking, which I myself bring forth, but at the object of thinking, which I do not bring forth.

I am even in the same case when I let the state of exception occur, and think about my thinking itself. I can never observe my present thinking; but only the experiences I have had of my thinking process can I afterwards make the object of thinking. I would have to split myself into two personalities: one that thinks and the other that watches itself thinking, if I wanted to observe my present thinking. I can't. I can only do that in two separate acts. The thinking that is to be observed is never the one in activity, but another. Whether I make my observations of my own earlier thinking for this purpose, or whether I follow the thought process of another person, or finally whether, as in the above case with the movement of the billiard balls, I presuppose a fictitious thought process, it does not matter.

Two things are not compatible: active production and contemplative juxtaposition. The first book of Moses already knows this. In the first six days of the world, God brings forth the world, and only when it is there is it possible to contemplate it: "And God looked upon all that he had made, and, behold, it was very good. So it is with our thinking. It has to be there first if we want to observe it.

The reason that makes it impossible for us to observe thinking in its present course is the same as that which allows us to recognise it more directly and intimately than any other process in the world. Precisely because we produce it ourselves, we know the characteristic of its course, the way in which the events involved take place. What can only be found indirectly in the other spheres of observation: the factually corresponding connection and the relationship of the individual objects, we know quite directly in thinking. Why, for my observation, thunder follows lightning, I do not know without further ado; why my thinking connects the concept of thunder with that of lightning, I know directly from the contents of the two concepts. Of course, it does not matter at all whether I have the right concepts of lightning and thunder. The connection of the ones I have is clear to me, and that is through them themselves.

This transparent clarity with regard to the thinking process is quite independent of our knowledge of the physiological basis of thinking. I speak here of thinking in so far as it arises from the observation of our mental activity. How one material process of my brain causes or influences another while I am carrying out a thought operation is not even a consideration. What I observe in thinking is not which process in my brain connects the concept of lightning with that of thunder, but what causes me to bring the two concepts into a certain relationship. My observation shows that I have nothing to base my thought connections on but the content of my thoughts; I do not base my thoughts on the material processes in my brain. For a less materialistic age than ours, this remark would of course be completely superfluous. But at the present time, when there are people who believe that if we know what matter is, we will also know how matter thinks, it must be said that it is possible to speak of thinking without immediately coming into collision with brain physiology. It is becoming difficult for many people today to grasp the concept of thinking in its purity. Anyone who immediately opposes the idea I have developed here of thinking with Cabanis' sentence: "The brain secretes thoughts like the liver secretes bile, the salivary gland secretes saliva, etc." simply does not know what I am talking about. He seeks to find thought by a mere process of observation in the same way that we proceed with other objects of world content. But he cannot find it in this way because, as I have proved, it is precisely there that it eludes normal observation. He who cannot overcome materialism lacks the ability to bring about in himself the exceptional state I have described, which makes him conscious of what remains unconscious in all other mental activity. Anyone who does not have the good will to put himself in this position could no more be spoken to about thinking than one could speak to a blind man about colour. But let him not believe that we consider physiological processes to be thinking. He does not explain thinking because he does not see it at all. But for anyone who has the ability to observe thinking - and with good will, every normally organised person has it - this observation is the most important one he can make. For he observes something of which he himself is the producer; he does not see himself confronted with what is at first an alien object, but with his own activity. He knows how what he observes comes about. He sees through the circumstances and relationships. A firm point is gained from which one can search with well-founded hope for the explanation of the remaining world phenomena.“ (Lit.:GA 4, p. 42)

„If thinking is made the object of observation, something is added to the rest of the observed world content that otherwise escapes attention; but the way in which man also behaves towards other things is not changed. One increases the number of objects of observation, but not the method of observation. While we observe other things, a process is mixed into world events - to which I now include observation - that is overlooked. There is something different from all other events that is not taken into account. But when I look at my thinking, there is no such unconsidered element. For what now hovers in the background is itself only thinking. The observed object is qualitatively the same as the activity directed towards it. And this is again a characteristic peculiarity of thinking. When we make it the object of observation, we do not find ourselves compelled to do this with the help of a qualitatively different thing, but we can remain in the same element.“ (Lit.:GA 4, p. 47)

We do not bring forth nature by perceiving it and subsequently recognising it. Perceptions are given to us without our intervention through the activity of our external and internal senses. It is different when we observe thought itself. We then observe something that we ourselves bring forth, namely our own spiritual activity.

„What is impossible in nature: creation before cognition; in thinking we accomplish it. If we wanted to wait with thinking until we had recognised it, we would never get to it. We have to think resolutely in order to arrive afterwards at its cognition by means of the observation of what we do ourselves. We ourselves first create an object for the observation of thinking. The existence of all other objects has been provided for without our intervention.

So there is no doubt: in thinking we hold world events at a point where we have to be present if anything is to come about. And that is precisely what matters. That is precisely the reason why things are so mysterious to me: that I am so uninvolved in how they come about. I simply find them; but in thinking, I know how it is done. Therefore, there is no more original starting point for the contemplation of all world events than thinking.“ (Lit.:GA 4, p. 49)

Literature

- Aristotle: Metaphysik, II. Teil, VII. Das Absolute, 2. Das absolute Prinzip pdf

- Christian Clement: Die Geburt des modernen Mysteriendramas aus dem Geiste Weimars. Zur Aktualität Goethes und Schillers in der Dramaturgie Rudolf Steiners., Logos Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8325-1645-1

- Bernardo J. Gut: Inhaltliches Denken und formale Systeme – Der platonische Standpunkt in Logik, Mathematik und Erkenntnistheorie, Verlag Rolf Kugler, Oberwil bei Zug 1979 [1]

- Jürgen Strube: Die Beobachtung des Denkens: Rudolf Steiners 'Philosophie der Freiheit' als Weg zur Bildekräfte-Erkenntnis, 3. Auflage, Verlag für Anthroposophie 2017, ISBN 978-3037690239

- Renatus Ziegler: Intuition und Ich-Erfahrung: Erkenntnis und Freiheit zwischen Gegenwart und Ewigkeit, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2006, ISBN 978-3772517853

- Renatus Ziegler: Dimensionen des Selbst: Eine philosophische Anthropologie, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2013, ISBN 978-3772524974

- Otto Jachmann: Denken wird Wahrnehmung: Die Philosophie von Brentano, Husserl, Heidegger und Derrida und die Anthroposophie, Verlag Christian Möllmann 2009, ISBN 978-3899791266

- Rudolf Steiner: Wahrheit und Wissenschaft, GA 3, 5. Auflage. Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach 1980, ISBN 3-7274-0030-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Philosophie der Freiheit, GA 4 (1995) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Vom Menschenrätsel, GA 20 (1984), ISBN 3-7274-0200-8 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Das Ewige in der Menschenseele. Unsterblichkeit und Freiheit, GA 67 (1992), ISBN 3-7274-0670-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Was wollte das Goetheanum und was soll die Anthroposophie?, GA 84 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-0840-5 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Beantwortung von Welt- und Lebensfragen durch Anthroposophie, GA 108 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-1081-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Der Mensch als Zusammenklang des schaffenden, bildenden und gestaltenden Weltenwortes, GA 230 (1993), ISBN 3-7274-2300-5 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Mysteriengestaltungen, GA 232 (1998), Erster Vortrag, Dornach, 23. November 1923 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis, GA 322 (1981), ISBN 3-7274-3220-9 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |

Weblinks

- Philosophy Of Freedom: Observation Of Thinking Exercises, based on Jügen Strube's "The Observation Of Thinking ― Rudolf Steiner’s 'Philosophy of Freedom' As a Path to the Knowledge of Formative-forces" - philosophyoffreedom.com