John Scotus Eriugena: Difference between revisions

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

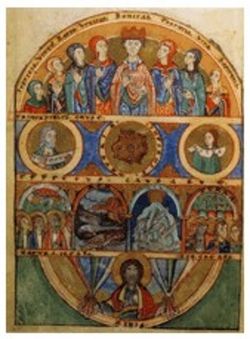

{{GZ|It is extremely important to take a close look at how Johannes Scotus Erigena structured his knowledge. In his great writing on the division of nature, which has just come down to posterity in the manner described, he distinguishes in four chapters what he has to say about the world, and in the first chapter he speaks of the non-created and creating world (see illustration p. 262). This is the first chapter that describes, in the way Johannes Scotus Erigena believes he can, God as he was before he approached anything that is world creation. Johannes Scotus Erigena describes God in the way he has learned from the writings of Dionysius, and he describes him by developing the highest concepts of understanding, but at the same time he is aware that with these one can only reach a certain limit, beyond which lies negative theology. Thus one only approaches what is actually the true essence of the spiritual, of the divine. In this chapter we find, among other things, the beautiful treatise on the divine Trinity, which is still instructive for today. He says that when we look at the things around us, we first find being as an all-spiritual quality (see p. 262). This Being is, as it were, that which encompasses everything. We should not ascribe to God the being that things have, but we can only speak, in a sense, of the being of the Godhead by looking up to what is beyond being. In the same way we find that things in the world are radiated and permeated with wisdom. We should not attribute to God mere wisdom, but superscience. But it is precisely when we start from things that we come to the limit of wisdom. But there is not only wisdom in all things: All things live; there is life in all things. So when John Scotus Erigena visualises the world, he says: I see in the world being, wisdom, life. The world appears to me, as it were, in these three aspects as being, as wisdom, as living. As it were, these are three veils that the mind forms when it looks over things. One would have to see through the veils, then one would see into the divine-spiritual. But he first describes the veils and says: "When I look at Being, it represents to me the Father; when I look at Wisdom, it represents to me the Son in the All; when I look at Life, it represents to me the Holy Spirit in the All|204|261ff}} | {{GZ|It is extremely important to take a close look at how Johannes Scotus Erigena structured his knowledge. In his great writing on the division of nature, which has just come down to posterity in the manner described, he distinguishes in four chapters what he has to say about the world, and in the first chapter he speaks of the non-created and creating world (see illustration p. 262). This is the first chapter that describes, in the way Johannes Scotus Erigena believes he can, God as he was before he approached anything that is world creation. Johannes Scotus Erigena describes God in the way he has learned from the writings of Dionysius, and he describes him by developing the highest concepts of understanding, but at the same time he is aware that with these one can only reach a certain limit, beyond which lies negative theology. Thus one only approaches what is actually the true essence of the spiritual, of the divine. In this chapter we find, among other things, the beautiful treatise on the divine Trinity, which is still instructive for today. He says that when we look at the things around us, we first find being as an all-spiritual quality (see p. 262). This Being is, as it were, that which encompasses everything. We should not ascribe to God the being that things have, but we can only speak, in a sense, of the being of the Godhead by looking up to what is beyond being. In the same way we find that things in the world are radiated and permeated with wisdom. We should not attribute to God mere wisdom, but superscience. But it is precisely when we start from things that we come to the limit of wisdom. But there is not only wisdom in all things: All things live; there is life in all things. So when John Scotus Erigena visualises the world, he says: I see in the world being, wisdom, life. The world appears to me, as it were, in these three aspects as being, as wisdom, as living. As it were, these are three veils that the mind forms when it looks over things. One would have to see through the veils, then one would see into the divine-spiritual. But he first describes the veils and says: "When I look at Being, it represents to me the Father; when I look at Wisdom, it represents to me the Son in the All; when I look at Life, it represents to me the Holy Spirit in the All|204|261ff}} | ||

{{Quote|It seems to me that the division of nature takes four distinct forms. First, it is divided into one that creates and is not created; then into one that is created and creates; third, into one that is created and does not create; fourth, into one that does not create and is not created. Of these four divisions, two are opposed to each other, the third to the first, the fourth to the second. But the fourth falls under impossibilities, since its distinguishing feature is that it cannot be.|John Scotus Eriugena|''On the Division of Nature'', p. 10|ref=<ref>Johannes Scotus Erigena, Ludwig Noack (Übers.): ''Über die Eintheilung der Natur'', Verlag von L. Heimann, Berlin 1870, Erste Abtheilung, S. 3f [http://www.odysseetheater.org/jump.php?url=http://www.odysseetheater.org/ftp/bibliothek/Philosophie/Johannes_Scotus_Erigena/Johannes_Scotus_Erigena_Ueber_die_Einteilung_der_Natur.pdf#page=10&view=Fit]</ref>}} | |||

{{GZ|For him the world presents itself as a development into four "forms of nature". The first is 'creating and uncreated nature'. In it is contained the purely spiritual original ground of the world, from which the "creating and created nature" develops. This is a sum of purely spiritual beings and forces which, through their activity, first bring forth the "created and non-created nature" to which the world of the senses and man belong. These develop in such a way that they are absorbed into the 'non-created and non-creating nature' within which the facts of redemption, the religious means of grace, etc., operate.|18|88}} | |||

== Literatur == | == Literatur == | ||

Revision as of 15:22, 26 May 2021

John Scotus Eriugena or Johannes Scotus Erigena (* early 9th century; † late 9th century) was a West Frankish monk of Celtic-Irish origin who worked at the court of Charles the Bald (823-877) as a teacher of the seven liberal arts and wrote numerous philosophical and theological works. As was customary at the time, he based his teaching on the encyclopaedic work De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii ("The Marriage of Philology with Mercurius") by Martianus Capella, which he also commented on in detail. Through his logically clean line of thought in the theological argumentation, Scotus Eriugena was already preparing the scholastic way of thinking. Due to his good, if not excellent, knowledge of Greek, which was very rare at the time[1], he was able to translate many works of the Greek philosophers and Church Fathers into Latin and comment on them, thus making them accessible and contributing above all to the dissemination of Neoplatonic thought. His translation of the works of Dionysius Areopagita, which were drawn from deep esotericism and had a decisive influence on the Christian doctrine of Angels, was particularly significant. Eriugena also found significant inspiration in Gregory of Nyssa (* around 335/340; † after 394) and Maximus Confessor (* around 580; † 662). Eriugena's main work, the Periphyseon (Greek: Περὶ φύσεων "On Natures", "On the Classification of Nature"), divided into five books, provides rich information about his thought. In the School of Chartres, the works of John Scotus Eriugena were highly esteemed, but were later condemned several times because of their audacious thought and many copies of his writings were burned.

Life and work

Little is known about the life of Eriugena - an epithet he may have given himself. Because of his radical theories, he was often fiercely opposed. According to legend, the historical basis of which, however, cannot be ascertained and therefore remains doubtful, Scotus Erigena was later summoned to England or had to flee there, where he is said to have been murdered by his own students, possibly at the behest of the Pope, with their pens(!)[2]. His work miraculously survived for the most part.

„One could say that, as if by some kind of historical miracle, posterity has actually come to know the writings of John Scotus Erigena. Unlike other writings from the first centuries, which were similar and have been completely lost, they were preserved until the 11th and 12th centuries, and a few even into the 13th century. At that time they were declared heretical by the Pope, and orders were given that all copies had to be searched out and burned. Only much later were manuscripts from the 11th and 13th centuries found again in a lost monastery. In the 14th, 15th, 16th and 17th centuries nothing was known about Johannes Scotus Erigena. The writings had been burnt like similar writings which contained similar things from the same time and where one was happier from Rome's point of view: all other copies had been given over to the fire! Only a few of the Scotus Erigena remained.“ (Lit.:GA 204, p. 260)

„Those who are more or less inclined to rationalism, even if with sagacity and richness of spirit, will already grumble when they get to see, to see spiritually, what emanated from the Areopagite, and what then found a last significant revelation in this Erigena. In the last years of his life he was still a Benedictine prior. But his own monks, as the legend says - the legend; I am not saying that this is literally true, but if it is not quite true, it is approximately true - they worked him with pins until he was dead, because he still brought Plotinism into the ninth century. But beyond him lived his ideas, which were at the same time the further development of the Areopagite's ideas. His writings more or less disappeared until later times; they did, however, come down to posterity. In the 12th century, Scotus Erigena was declared a heretic. But that did not yet have the significance it has later and today. Nevertheless, Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas were also deeply influenced by the ideas of Scotus Erigena.“ (Lit.:GA 74, p. 51)

Periphyseon - On the division of nature

For a detailed discussion of the account, see Johannes Zahlten, Die Erschaffung von Raum und Zeit in Darstellungen zum Schöpfungsbericht von Genesis 1, in: Jan A. Aertsen and Andreas Speer (eds.), Raum und Raumvorstellungen im Mittelalter (= Miscellanea mediaevalia No. 25), de Gruyter, Berlin 1998, pp. 615-628, esp. pp. 615f.

Johannes Scotus Eriugena gave his main work, which is divided into 5 books and written as a dialogue between a teacher and his pupil, the title Periphyseon (Greek: Περὶ φύσεων "On natures"). The Latin title De divisione naturae (On the division of nature) does not come from him and is only verifiable from the 12th century onwards. It describes the relationship of the Creator to his creation, in particular to man, and the resulting cosmic world order in its entire development from beginning to end, both of which coincide into one for God, who stands above space and time.

„People today do not like to appreciate something like the work on the division of nature by Johannes Scotus Erigena in the 9th century. People don't get involved because they don't take such a work as a historical monument from a time when people thought in a completely different way than they do today, when people thought in a way that they no longer understand when they read such a work today. And when ordinary philosophers present such things in their historiography, one is really only dealing with words. The actual spirit of such a work, such as that of Johannes Scotus Erigena on the division of nature, where nature means something quite different from the word nature in later natural science, is not really there any more. If one can nevertheless enter into it with spiritual-scientific deepening, then one must say the following to oneself: this Scotus Erigena has developed ideas which make the impression on one that they go extraordinarily deeply into the essence of the world, but he has quite undoubtedly presented these ideas in an inadequate, not penetrating form in his work. If one were not to expose oneself to the danger of speaking disrespectfully of what is after all an outstanding work of human development, one would actually have to say that Johannes Scotus Erigena himself was no longer fully aware of what he was writing. One can see this in his account. For him, even if not to the same extent as for today's historians of philosophy, the words he took from tradition were more or less only words whose profound content he himself no longer understood. One is actually more and more compelled, when one reads these things, to go back in history. And from Scotus Erigena, as can easily be seen from his writings, one is led directly to the writings of the so-called Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. I don't want to go into this problem of development, when he lived and so on. And from this Dionysius the Areopagite one is led back again. Then one has to continue researching, really equipped with spiritual science, and one finally arrives, if one goes back to the second or third millennium of pre-Christian times, at profound insights which have been lost to humanity, which are only present in a faint echo in such writings as those of Johannes Scotus Erigena“ (Lit.:GA 326, p. 116f)

„It is extremely important to take a close look at how Johannes Scotus Erigena structured his knowledge. In his great writing on the division of nature, which has just come down to posterity in the manner described, he distinguishes in four chapters what he has to say about the world, and in the first chapter he speaks of the non-created and creating world (see illustration p. 262). This is the first chapter that describes, in the way Johannes Scotus Erigena believes he can, God as he was before he approached anything that is world creation. Johannes Scotus Erigena describes God in the way he has learned from the writings of Dionysius, and he describes him by developing the highest concepts of understanding, but at the same time he is aware that with these one can only reach a certain limit, beyond which lies negative theology. Thus one only approaches what is actually the true essence of the spiritual, of the divine. In this chapter we find, among other things, the beautiful treatise on the divine Trinity, which is still instructive for today. He says that when we look at the things around us, we first find being as an all-spiritual quality (see p. 262). This Being is, as it were, that which encompasses everything. We should not ascribe to God the being that things have, but we can only speak, in a sense, of the being of the Godhead by looking up to what is beyond being. In the same way we find that things in the world are radiated and permeated with wisdom. We should not attribute to God mere wisdom, but superscience. But it is precisely when we start from things that we come to the limit of wisdom. But there is not only wisdom in all things: All things live; there is life in all things. So when John Scotus Erigena visualises the world, he says: I see in the world being, wisdom, life. The world appears to me, as it were, in these three aspects as being, as wisdom, as living. As it were, these are three veils that the mind forms when it looks over things. One would have to see through the veils, then one would see into the divine-spiritual. But he first describes the veils and says: "When I look at Being, it represents to me the Father; when I look at Wisdom, it represents to me the Son in the All; when I look at Life, it represents to me the Holy Spirit in the All“ (Lit.:GA 204, p. 261ff)

„It seems to me that the division of nature takes four distinct forms. First, it is divided into one that creates and is not created; then into one that is created and creates; third, into one that is created and does not create; fourth, into one that does not create and is not created. Of these four divisions, two are opposed to each other, the third to the first, the fourth to the second. But the fourth falls under impossibilities, since its distinguishing feature is that it cannot be.“

„For him the world presents itself as a development into four "forms of nature". The first is 'creating and uncreated nature'. In it is contained the purely spiritual original ground of the world, from which the "creating and created nature" develops. This is a sum of purely spiritual beings and forces which, through their activity, first bring forth the "created and non-created nature" to which the world of the senses and man belong. These develop in such a way that they are absorbed into the 'non-created and non-creating nature' within which the facts of redemption, the religious means of grace, etc., operate.“ (Lit.:GA 18, p. 88)

Literatur

- Johannes Scotus Erigena, Ludwig Noack (Übers.): Über die Eintheilung der Natur, Verlag von L. Heimann, Berlin 1870 pdf

- Wolf-Ulrich Klünker: Johannes Scotus Eriugena - Denken im Gespräch mit dem Engel, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 978-3-7725-0826-4

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Mystik im Aufgange des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens und ihr Verhältnis zur modernen Weltanschauung, GA 7 (1990), ISBN 3-7274-0070-6 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache und die Mysterien des Altertums, GA 8 (1989), ISBN 3-7274-0080-3 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Rätsel der Philosophie in ihrer Geschichte als Umriß dargestellt, GA 18 (1985), ISBN 3-7274-0180-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Über Philosophie, Geschichte und Literatur, GA 51 (1983), ISBN 3-7274-0510-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Philosophie des Thomas von Aquino, GA 74 (1993), ISBN 3-7274-0741-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Perspektiven der Menschheitsentwickelung, GA 204 (1979), ISBN 3-7274-2040-5 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Menschenwerden, Weltenseele und Weltengeist – Zweiter Teil, GA 206 (1991), ISBN 3-7274-2060-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Das Geheimnis der Trinität, GA 214 (1999), ISBN 3-7274-2140-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Der Entstehungsmoment der Naturwissenschaft in der Weltgeschichte und ihre seitherige Entwickelung, GA 326 (1977), ISBN 3-7274-3260-8 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |

References

- ↑ Where and how Eriugena acquired this knowledge of Greek remains unclear. In the monasteries of his Irish homeland, people had an elementary knowledge of the Greek language, but certainly not at Eriugena's level. In his thinking, he shows great sympathy for the clearly more spiritual Greek Eastern Church, which at that time was not yet officially divorced from the Western Church, but was already separated from it by a great spiritual gap. Thus, at the Fourth Council of Constantinople (869), the teachings of Photios I were rejected and the trichotomy, the threefold division of the human being into body, soul and spirit, was condemned as heretical - and thus the spirit of the human being "abolished", as Rudolf Steiner often put it. However, whether Eriugena came into contact with scholars of the Eastern Church and whether Eruigena also undertook journeys to Byzantium or Greece remains obscure.

- ↑ Which is perhaps only to be understood metaphorically in the sense of a refutation of his writings.

- ↑ Johannes Scotus Erigena, Ludwig Noack (Übers.): Über die Eintheilung der Natur, Verlag von L. Heimann, Berlin 1870, Erste Abtheilung, S. 3f [1]