Waldorf education

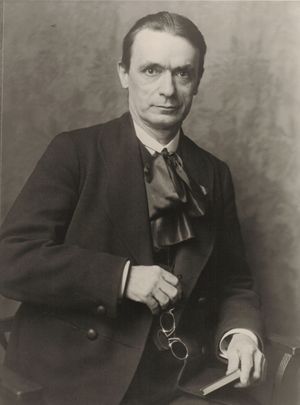

Waldorf education is a teaching and educational method developed by Rudolf Steiner, which aims to promote the free development of the unique individuality of the growing child to the best of its ability.

„A riddle of nature which he has to solve, every growing human being should be to the man who wants to be an educator.“ (Lit.:GA 52, p. 216)

Waldorf educational institutions

Waldorf education is applied and developed today primarily in the following institutions:

Waldorf education differs from many other educational methods in that it does not seek to lead the child primarily towards ready-made educational goals, but seeks to awaken the forces that - quite individually - lie dormant within the child itself.

„Waldorf education is not a pedagogical system at all, but an art to awaken what is there in the human being. Basically, Waldorf education does not want to educate, but to awaken. For today it is a question of waking up. First the teachers must be awakened, then the teachers must again awaken the children and young people.“ (Lit.:GA 217, p. 36)

Clear knowledge of the human being as the basis of education

Real art of education requires a very clear, fact-oriented knowledge of the human being and its development. Rudolf Steiner even consciously uses the comparison with the machine. Not because the human being is a machine, that is certainly not the case, but just as one must know exactly how its parts must work together in order for it to run well, so one must also recognise in the human being, with a clear, downright sober mind, quite concretely how his or her essential members (physical body, etheric body, astral body and I) best work together in order to ensure good development.

„Not general phrases, such as 'harmonious training of all powers and dispositions' and the like, can be the basis of a genuine art of education, but only on a real knowledge of the human being can such an art be built." It is not to be asserted that the phrases alluded to are incorrect, but only that nothing can be done with them, just as if one were to assert to a machine, for instance, that all its parts must be made to work harmoniously. Only those who approach it not with general phrases, but with real knowledge of the machine in detail, can handle it. Thus, for the art of education, too, it is a question of knowledge of the members of the human being and their development in detail.... One must know which part of the human being one has to influence at a certain age, and how this influence is to be done properly. There is no doubt that a truly realistic art of education, as indicated here, can only develop slowly. This is due to the way of looking at things in our time, which will continue for a long time to regard the facts of the spiritual world as the outflow of a fantastic imagination, while general, completely unreal sayings will appear to it to be the result of a realistic way of thinking. Here is to be drawn without reserve what at present will be taken by many as a fantasy painting, but what will one day be taken for granted.“ (Lit.:GA 34, p. 322f)

Promoting individuality

Even if the knowledge of the human being in general forms the necessary basis of pedagogy, every human being is unique and must therefore be supported in a completely individual way in order to develop his or her special abilities.

„Dogmas, principles and doctrines do not matter; what matters is life and the realisation of the forces which flow from selflessness and thereby from the ability to perceive the spirit.“ (Lit.:GA 52, p. 216)

The pedagogy appropriate to the growing child is to be read off again and again from the growing child itself - with the teacher's or educator's own personality being set aside as far as possible.

„An erasure of one's own personality in a certain sense is now also necessary in a single task that has infinite importance for the most everyday human life, in human education. In every growing human being, from the birth of the child, through the years of development, it is the spirit in the innermost core of the human being that is to develop; the spirit that at first rests hidden within the body, rests hidden within the soul emotions of the developing human being. If we confront this spirit, with our interests - I don't even want to say wishes and desires -, if we make the developing human being dependent on our interests, then we let our spirit flow into the human being and we basically develop what is in us in the developing human being. But I do not even want to speak of letting our wishes and desires be active in the education of a growing human being, but only of the fact that all too often, indeed that it is almost the rule, that the educator lets his intellect speak, that the educator asks his reason above all things what has to be done for this or that educational measure. In doing so, he does not take into account that he has before him a developing spirit which can only form itself according to its nature if it can develop freely and unhindered on all sides according to this nature, and if the educator gives it the opportunity for this development. We have an alien human spirit before us. We must allow an alien human spirit to have an effect on us if we are educators. As we have seen that in hypnosis, in the abnormal state, the spirit acts directly upon the human being, so in another form, when we have the child before us, the developing spirit of the child acts directly upon us and must act upon us. But this spirit will only be able to be trained by us if we are able to extinguish ourselves, just as we do in other higher pursuits, if we are able to be, without interference of our self, a servant of the human spirit entrusted to us for education, if this human spirit is given by us the opportunity to develop freely.“ (Lit.:GA 52, p. 213f)

The fundamental importance of art for Waldorf education

By its very nature, science can only grasp that which is universally valid. Art, on the other hand, arises from individual creative activity. The artistic attitude and ability are therefore particularly suited to grasping the individual nature of the child. Pedagogy in Rudolf Steiner's sense should therefore not be based one-sidedly on any kind of educational science, but should become a real art of education. Artistic creation and feeling therefore form the methodological basis of teaching in every subject, especially in those subjects which seem to have little or nothing to do with art, such as mathematics, geography, biology, chemistry, physics, etc.

„If you want to educate people with abstract scientific content, they will not experience anything of your soul. He will only experience something of his soul if you confront him artistically, because in the artistic each person must be individual, in the artistic each person is different. The scientific ideal is precisely that everyone is like everyone else. It would be a beautiful story - as they say nowadays - if everyone taught a different science. That can't be, because science is reduced to that which is the same for all people. In art, however, each person is an individuality. Through the artistic, therefore, an individual relationship of the child to the stimulating and active human being can come about, and that is necessary. It is true that in this way one does not, as in the first years of childhood, have a total physical feeling of the other human being, but one does have a total feeling of the soul of the one who stands opposite one as a guide.

Education must have soul, but as a scientist one cannot have soul. One can only have soul through what one is artistically. One can have soul if one shapes science artistically by the way one presents it, but not by the content of science as it is conceived today. Science is not an individual matter. Therefore, it does not establish a relationship between the leader and the led at the age of compulsory schooling. All teaching must be permeated by art, by human individuality, and it is the individuality of the teacher and educator that is more important than any elaborate programme. It is this that must work in the school.“ (Lit.:GA 217, p. 160)

„We cannot become educators by studying. We cannot train others to be educators, for the very reason that each of us is one. There is an educator in every human being; but this educator is asleep, he must be awakened, and the artistic is the means of awakening. When this is developed, it brings the educator as a human being closer to those he wants to lead. The person to be educated must come close to the educator as a human being, he must have something of him as a human being. It would be dreadful if someone wanted to believe that he could be an educator because he knows a lot or can "do" a lot in the sense of knowledge, which is even possible to say today.“ (S. 162)

„What I have learned has no significance at all for what I am to the child as an educator until the change of teeth. After the change of teeth, it already begins to have a certain significance. But it loses all meaning when I teach it the way I carry it inside me. It has to be translated artistically, everything has to be brought into the picture, as we shall see. I must again awaken imposing forces between myself and the child. And for the second epoch of life, for the epoch of life from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, it is much more important than the abundance of material I have learnt, much more important than what I carry in me, in my head, whether I can translate into vivid imagery, into living design, what I develop around the child and let ripple into the child. And only for those who have already passed through sexual maturity, and for these then up to the beginning of the twenties, does what one has learned oneself take on significance. For the small child up to the change of teeth, the most important thing in education is the person. For the child from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, the most important thing in education is the human being who is becoming a living artist. And it is not until the child is fourteen or fifteen years old that he or she demands for educational instruction and teaching what one has learned oneself, and this lasts until after the twentieth or twenty-first year, when the child is quite grown up - he or she is already a young lady and a young man - and when the twenty-year-old then stands opposite the other human being as an equal, even if he or she is older.“ (Lit.:GA 308, p. 22)

Especially in the period from the 7th to the 14th year of life, the artistic organisation of lessons is of essential importance for the child's development. Everything must be brought to the child in a pictorial-artistic way.

„Between the change of teeth and sexual maturity, the child is an artist, albeit in a childlike way, just as in the first epoch of life up to the change of teeth it is in a natural way a homo religiosus, a religious being. Since the child now demands to receive everything in a pictorial-artistic way, the teacher, the educator, has to face him as one who brings everything he brings to the child as an artistically formative one. This is what must be demanded of the educator and teacher of our present-day culture, what must flow into the art of education. Artistic things must take place between the change of teeth and sexual maturity between the teacher and the growing human being. In this respect, we as teachers have many things to overcome. For our civilisation and culture, which at first surround us externally, have become so that they are calculated only for the intellect, that they are not yet calculated for the artistic.“ (Lit.:GA 308, p. 37)

Literatur

- Stefan Leber: Die Menschenkunde der Waldorfpädagogik: Anthropologische Grundlagen der Erziehung des Kindes und Jugendlichen, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 1993, ISBN 978-3772502613

- Wilfried Gabriel: Personale Pädagogik in der Informationsgesellschaft. Berufliche Bildung, Selbstbildung und Selbstorganisation in der Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners, Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften 1995, ISBN 978-3631479124

- Michaela Strauss, Wolfgang Schad (Hrsg.): Von der Zeichensprache des kleinen Kindes: Spuren der Menschwerdung - mit menschenkundlichen Anmerkungen von Wolfgang Schad, 6. Auflage, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2007, ISBN 978-3772521348

- Ernst-Michael Kranich: Anthropologische Grundlagen der Waldorfpädagogik, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 978-3772517815

- Jost Schieren (Hrsg.): Handbuch Waldorfpädagogik und Erziehungswissenschaft, Beltz-Juventa, Weinheim - Basel 2016, ISBN 978-3-7799-3129-4

- Johannes Kiersch: Die Waldorfpädagogik: Eine Einführung in die Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3772526848; eBook ASIN B018UD710A

- Johannes Kiersch: „Mit ganz andern Mitteln gemalt“ - Überlegungen zur hermeneutischen Erschließung der esoterischen Lehrerkurse Steiners, in: Research on Steiner Education Vol.1 No.2 2010 pdf

- Ernst-Christian Demisch (Hersg.), Christa Greshake-Ebding (Hrsg.), Johannes Kiersch (Hrsg.): Steiner neu lesen: Perspektiven für den Umgang mit Grundlagentexten der Waldorfpädagogik (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 12), Peter Lang GmbH 2014, ISBN 978-3631649695, eBook ASIN B076FCC8PN

- Horst Philipp Bauer (Hrsg.), Peter Schneider (Hrsg.): Waldorfpädagogik: Perspektiven eines wissenschaftlichen Dialoges (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 1), Peter Lang GmbH 2005, ISBN 978-3631546338

- Uwe Mingo: Leitfaden und Praxishandbuch zu Rudolf Steiners Pädagogik, Achamoth Vlg., Schönach/Bodensee 1998, ISBN 3-923302-08-8

- Frans Carlgren: Erziehung zur Freiheit. Die Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners, 11. Auflage, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2016, ISBN 978-3772516191

- Henning Kullak-Ublick: Jedes Kind ein Könner: Fragen und Antworten zur Waldorfpädagogik, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2017, ISBN 978-3772528736, eBook ASIN B073SDDWT9

- Gerhard Wehr: Der pädagogische Impuls Rudolf Steiners. Theorie und Praxis der Waldorfpädagogik, Fischer-TB, Frankfurt a.M. 1983, ISBN 3-596-25521-X

- Heinz Brodbeck (Hrsg.), Robert Thomas (Hrsg.): Steinerschulen heute: Ideen und Praxis der Waldorfpädagogik, Zbinden Verlag 2019, ISBN 978-3859894549

- Tobias Richter (Hrsg.): Pädagogischer Auftrag und Unterrichtsziele - vom Lehrplan der Waldorfschule, 4. Auflage, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3772526695, eBook ASIN B01N1I5NCE

- Rüdiger Blankertz: 'Das Erfolgsmodell' Waldorfschule und 'das Problem' Rudolf Steiner, Edition Nadelöhr 2019, ISBN 978-3952508015

- Valentin Wember: Was will Waldorf wirklich? Die unbekannte Erziehungskunst Rudolf Steiners. Ein Vortrag für Eltern und Lehrer. Stratosverlag 2019, ISBN 9783943731286

- Rudolf Steiner

- Rudolf Steiner: Spirituelle Seelenlehre und Weltbetrachtung, GA 52 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-0520-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Westliche und östliche Weltgegensätzlichkeit, GA 83 (1981), ISBN 3-7274-0830-8 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Geistige Wirkenskräfte im Zusammenleben von alter und junger Generation. Pädagogischer Jugendkurs., GA 217 (1988), ISBN 3-7274-2170-3 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Ritualtexte für die Feiern des freien christlichen Religionsunterrichtes und das Spruchgut für Lehrer und Schüler der Waldorfschule, GA 269 (1997), ISBN 3-7274-2690-X Template:Lectures 1

- Rudolf Steiner: Idee und Praxis der Waldorfschule, GA 297 (1998), ISBN 3-7274-2970-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Rudolf Steiner in der Waldorfschule, GA 298 (1980) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Konferenzen mit den Lehrern der Freien Waldorfschule 1919 bis 1924, Band I: Ausführliche Einleitung (E. Gabert) / Konferenzen 1919–1921, GA 300a (1995), ISBN 3-7274-3000-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die gesunde Entwickelung des Menschenwesens. Eine Einführung in die anthroposophische Pädagogik und Didaktik., GA 303 (1978), ISBN 3-7274-3031-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die pädagogische Praxis vom Gesichtspunkte geisteswissenschaftlicher Menschenerkenntnis. Die Erziehung des Kindes und jüngeren Menschen., GA 306 (1956) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Methodik des Lehrens und die Lebensbedingungen des Erziehens, GA 308 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-3080-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Heilpädagogischer Kurs, GA 317 (1995), ISBN 3-7274-3171-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |

- Kritische Literatur

- Klaus Prange: Erziehung zur Anthroposophie: Darstellung und Kritik der Waldorfpädagogik, 3. Auflage, Klinkhardt 2000, ISBN 978-3781510890

- Sybille-Christin Jacob, Detlef Drewes: Aus der Waldorfschule geplaudert: Warum die Steiner-Pädagogik keine Alternative ist, 2. Auflage, Alibri Verlag 2004, ISBN 978-3932710841

- Heiner Ullrich: Waldorfpädagogik: Eine kritische Einführung, Beltz Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3407257215; eBook ASIN: B010U1P15C

- Hellmich, Achim und Teigeler, Peter (Hrsg.): Montessoripädagogik, Freinetpädagogik, Waldorfpädagogik - Konzeption und aktuelle Praxis. Beltz Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3407252188