Clairvoyance

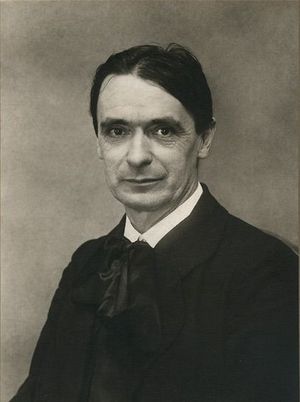

Clairvoyance generally refers to the ability of non-sensory perception in the broadest sense. People who possess this ability are called clairvoyants - or seers for short. Clairvoyance in the sense meant by Rudolf Steiner is directed towards the perception of the higher supersensible worlds. Modern clairvoyance is based on the trained ability of imagination, which, unlike the old dream-like clairvoyance, is a fully conscious, purely soul-spiritual perception. This includes in particular reading the Akasha Chronicle, the spiritual world memory, in which, however, one does not directly see the outer sensual events, but the spiritual archetypes from which they have emerged.

Imagination differs from vision, in which imaginatively perceived spiritual phenomena in the astral world are unconsciously transferred to the sensual daytime consciousness and directly sensualised. The heightened sensory-free imaginative consciousness, which is brighter than normal everyday consciousness, also excludes any confusion with mere phantasy, arbitrary imaginings or even hallucinations. The clairvoyant ability is all the more highly and purely developed, the higher realms of the world can thereby be perceived in a purely supersensory way. Imagination also differs from extrasensory perception, as it is also studied in parapsychology. This can refer, as was the case with Swedenborg, for example, to simultaneous but distant events, but also to past or future physical events, in which latter case one speaks of precognition.

The evolution of human consciousness

A deeper understanding of the phenomenon of clairvoyance, which today seems disreputable to many people with some justification, can only be gained by considering that human consciousness was not always as we know it today. Just as the human body only developed into its present form in the course of millions of years of evolution, human consciousness has also changed decisively in the course of human development. While palaeontology tries to reconstruct the development of the modern human body from more or less sparse fossil finds, we are in a better position with regard to consciousness because older forms of consciousness are still accessible to our direct experience to a certain extent, even if only in a considerably modified form. In addition to modern waking consciousness, which is divided by the modern subject-object split into object consciousness and I-consciousness, we also know dream consciousness and dreamless sleep consciousness. The latter, however, is so dull that we only experience it indirectly through the absence of any conscious experience. Here we have the apparent paradox of an "unconscious consciousness" or a subconscious. That this nevertheless has a significant influence on our lives is taught to us not least by depth psychology. An even more difficult form of consciousness to access is the trance consciousness, as it can occasionally appear in medially inclined persons. The ancient clairvoyance that mankind has long had at its disposal is rooted in these old forms of consciousness. What they have in common is that they lack clear I-consciousness.

Man has little influence on the future development of his body. The situation today is quite different with regard to consciousness. The human being can, if he wants to, actively develop it out of his full I-consciousness through appropriate spiritual training. This is the basis for the ability of imagination already mentioned above, which makes possible a prudent new clairvoyance connected with the clear insight of the full I-consciousness.

„It has often been pointed out, and will be further explained, that the development of human consciousness took place in such a way that dreamlike, clairvoyant states - the word should not be misused here, as is the case in many fields today - were the states of consciousness of the actual normal human being in ancient times, so that man did not see the world in terms of concepts and ideas, in strictly circumscribed sensual perceptions, as he sees it today. The best way to get an idea of how man in primitive times absorbed the world around him into his consciousness is to think of the last remnants of the old primal consciousness: the dream consciousness. Everyone is familiar with the dream images that surge up and down, which today are for the most part meaningless to the human consciousness, and which are often only reminiscences of the outer world, although higher types of consciousness can also be involved, but which today's man finds difficult to interpret. Dream consciousness - we can say - proceeds pictorially, in rapidly changing images, but at the same time symbolically. Who would not have experienced how the impression, the whole event of a fire reveals itself symbolically in a dream? Direct your gaze for once to this different kind of consciousness, to this different kind of horizon of consciousness, as it is present in the dream; as it is there, it is only the last remnant of an ancient human consciousness. But this ancient consciousness was such that man indeed lived in a kind of images. These images did not refer to the indeterminate or to nothing, but to a real external world. In the states of consciousness of ancient humanity there were intermediate states between waking and sleeping, and in these intermediate states man lived in relation to the spiritual world. This spiritual world entered his consciousness. Today the gate of the spiritual world is closed to the normal human consciousness. In ancient times it was not so. Man had the intermediate states between waking and sleeping; then he saw in pictures which, though similar to dream pictures, clearly represented spiritual being and spiritual weaving, as it is behind the physical-sensual world. So that man in ancient times really did have - though in Zarathustra's time already rather indistinctly and vaguely - but nevertheless a direct observation and experience of the spiritual world and could say: Just as I see the outer physical world and the sensuous life, so I know that there are experiences and observations of another state of consciousness, that another world, a spiritual one, underlies the sensuous.

The meaning of the development of mankind consists in the fact that from epoch to epoch man's ability to see into the spiritual world became smaller and smaller, because the abilities develop in such a way that one always has to be bought at the expense of the other. Our present-day exact thinking, our imagination, our logic, everything that we call the most important driving wheels of our culture, did not exist at that time. Man had to buy it in that epoch, which is already ours, at the cost of the old clairvoyant state of consciousness. That is what man has to develop today. And in the future evolution of mankind, the old clairvoyant state will be added to the purely physical consciousness with intellectuality and logic. A descent and an ascent must therefore be distinguished in relation to human consciousness. There is a profound meaning in the development when we say that man first lived with his whole soul-life still in a spiritual world, then descended into the physical world and had to give up the old clairvoyant consciousness for this purpose, so that he could acquire intellectuality, logic, in accordance with the physical world - educated by the purely physical world - in order then in the future to ascend again into the spiritual world.“ (Lit.:GA 60, p. 255ff)

Epistemological basis

Idealising oil painting by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1828

For Steiner, the starting point of modern self-aware clairvoyance is the observation of thinking, i.e. the intellectual view of one's own thinking activity, through which the I becomes aware of itself, independent of its physical organisation, as a purely spiritual being. Steiner thus ties in directly with the philosophy of German idealism, namely Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling. On 13 January 1881, at 12 midnight, he wrote to his childhood friend Josef Köck in this regard:

„It was the night of 10 to 11 January, during which I did not sleep for a moment. I had been occupied with individual philosophical problems until half past one in the morning, and then I finally threw myself onto my bed; last year, my endeavour was to investigate whether it was true what Schelling said: "We all have a secret, wonderful ability to withdraw from the change of time into our innermost self, stripped of everything that came from outside, and there, under the form of immutability, to look at the eternal in us. I believed and still believe that I have discovered this innermost faculty quite clearly in myself - I had suspected it long ago -; the whole idealistic philosophy now stands before me in an essentially modified form; what is a sleepless night against such a discovery!“ (Lit.:GA 38, p. 13)

Another important foundation of a different kind for Steiner was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's "Anschauende Urteilskraft" (visual power of judgement), which was directed towards the sensual-supersensory perception of nature and which had led him to the experience of the primordial plant. It is the ideal archetype, the conceptual and at the same time vivid archetype from which all plant species can be imagined to have emerged through modification.

„The archetypal plant becomes the most wonderful creature in the world, which nature itself should envy me for. With this model and the key to it, one can then invent plants into infinity which must be consistent, that is, which, even if they do not exist, could nevertheless exist and are not picturesque or poetic shadows and appearances, but have an inner truth and necessity. The same law will apply to all other living things.“ (Lit.: Goethe's Works WA, p. 203 and 204)

Goethe starts with sensual perception and ends with intellectual perception, which reveals itself with, from and through sensual perception. He devoted his full attention to the immediate sensory impressions; his thinking never strayed far from immediate perception, just as his perceiving was never thoughtless. He writes about this in his essay «Bedeutende Förderung durch ein einziges geistreiches Wort» (Considerable advancement through a single witty word):

„Dr. Heinroth in his Anthropology ... speaks favourably of my nature and activity, indeed he describes my way of proceeding as a peculiar one: namely, that my faculty of thought is objectively active, by which he means that my thinking is not separate from the objects, that the elements of the objects, the views, enter into it and are penetrated by it in the most intimate way, that my viewing is itself a thinking, my thinking a viewing, which method the aforementioned friend does not wish to deny his applause.“ (Lit.: Goethes Werke, p. 77)

Goethe knew only one source of knowledge, the world of experience, in which the objective world of ideas is included. The primal plant is not accessible to discursive, logically deductive thinking, but only to direct, intuitive intellectual contemplation. Immanuel Kant had denied humans such a faculty. Goethe vigorously contradicted this:

„When I tried, if not to penetrate Kant's teaching, to make the best possible use of it, I sometimes thought that the delicious man was proceeding in a mischievously ironic manner, in that he seemed at times to be endeavouring to restrict the faculty of knowledge in the narrowest possible way, and at other times to be pointing with a sideways glance beyond the limits that he himself had drawn. He might have noticed, of course, how presumptuously and foolishly man proceeds when, comfortably equipped with little experience, he immediately and rashly denies and tries to establish something, a whim that runs through his brain, to cancel out the objects. That is why our master restricts his thinker to a reflective discursive power of judgement, forbids him a determining one altogether. Then, however, after he has sufficiently cornered us, even brought us to despair, he decides on the most liberal expressions and leaves it up to us to decide what use we want to make of the freedom that he to some extent allows. In this sense the following passage was most significant to me:

- «We can think of an understanding which, because it is not discursive like ours, but intuitive, goes from the synthetic general, the conception of a whole as such, to the particular, that is, from the whole to the parts: Here it is not at all necessary to prove that such an intellectus archetypus is possible, but only that we are led to that idea of an intellectus archetypus in the opposition of our discursive understanding (intellectus ectypus), which is in need of images, and the contingency of such a constitution, that this also contains no contradiction.»

It is true that the author here seems to point to a divine intellect, but if in the moral, through faith in God, virtue and immortality, we are to raise ourselves into an upper region and approach the first being: so it might well be the same case in the intellectual that, by beholding an ever-creating nature, we made ourselves worthy of spiritual participation in its productions. After all, if I had first unconsciously and out of an inner urge restlessly pushed towards that archetypal, typical thing, if I had even succeeded in building up a representation in keeping with nature, then nothing could now prevent me from courageously passing through the adventure of reason, as the old man from Königsberg himself calls it.“ (Lit.: Goethes Werke, p. 91)

Literature

- Karl von Meyenn (Hrsg.): Wolfgang Pauli. Wissenschaftlicher Briefwechsel, Band III: 1940–1949. Springer. Berlin (1993) Brief #929, S. 496

- H. Atmanspacher, H. Primas, E. Wertenschlag-Birkhäuser (Hrsg.), Der Pauli-Jung-Dialog, Springer Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 1995

- Goethes Werke, Vollständige Ausgabe in vierzig Teilen, Auf Grund der Hempelschen Ausgabe, Deutsches Verlagshaus Bong u. Co, Berlin Leipzig Wien Stuttgart, 38. Teil

- Goethes Werke (WA). Hrsg. im Auftrage der Großherzogin Sophie von Sachsen. Weimar 1887-1919. Abteilung IV 8, Briefe

- Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft, § 77

- Flensburger Hefte Nr. 66: Hellsehen - Der Blick über die Schwelle, Flensburger Hefte Vlg., Flensburg 1999

- Flensburger Hefte Nr. 107: Neues Hellsehen, Flensburger Hefte Vlg., Flensburg 2010

- Rudolf Steiner: Ein Weg zur Selbsterkenntnis des Menschen, GA 16 (2004), ISBN 3-7274-0160-5; zusammen mit GA 17 in Tb 602, ISBN 978-3-7274-6021-0 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Schwelle der geistigen Welt, GA 17 (1987), ISBN 3-7274-0170-2 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Philosophie und Anthroposophie, GA 35 (1984), ISBN 3-7274-0350-0 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Briefe Band I: 1881 – 1890, GA 38 (1985), ISBN 3-7274-0380-2 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Spirituelle Seelenlehre und Weltbetrachtung, GA 52 (1986), 30. März 1904, Berlin English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Erkenntnis der Seele und des Geistes, GA 56 (1985), ISBN 3-7274-0560-0 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Antworten der Geisteswissenschaft auf die großen Fragen des Daseins, GA 60 (1983), ISBN 3-7274-0600-3 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Das Lukas-Evangelium, GA 114 (2001) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die tieferen Geheimnisse des Menschheitswerdens im Lichte der Evangelien, GA 117 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-1170-8 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Wie erwirbt man sich Verständnis für die geistige Welt?, GA 154 (1985), ISBN 3-7274-1540-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Wege der geistigen Erkenntnis und der Erneuerung künstlerischer Weltanschauung, GA 161 (1980) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Kunst und Kunsterkenntnis, GA 271 (1985), ISBN 3-7274-2712-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |