Waldorf education: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

There is no reason to fear that the pupil will leave the primary schools in a state of mind and body alien to the outer life, if we look in the way described at that which results from the inner development of the human being as principles of instruction and education. For human life is itself formed out of this inner development, and the human being will enter this life in the best way when, through the development of his dispositions, he finds himself united with what, out of the human dispositions of the same kind, men before him have incorporated into the development of culture. However, in order to harmonise both the development of the pupil and the outer development of culture, it is necessary to have teachers who do not close themselves off with their interests in a specialised educational and teaching practice, but who place themselves with full participation in the vastness of life. Such teachers will find the possibility of awakening in young people a sense for the spiritual content of life, but no less an understanding for the practical shaping of life. With such an attitude to teaching, the fourteen- or fifteen-year-old will not be without understanding for the essentials of agriculture, industry and traffic which serve the life of humanity as a whole. The insights and skills he has acquired will enable him to feel oriented in the life that welcomes him.|298|9ff}} | There is no reason to fear that the pupil will leave the primary schools in a state of mind and body alien to the outer life, if we look in the way described at that which results from the inner development of the human being as principles of instruction and education. For human life is itself formed out of this inner development, and the human being will enter this life in the best way when, through the development of his dispositions, he finds himself united with what, out of the human dispositions of the same kind, men before him have incorporated into the development of culture. However, in order to harmonise both the development of the pupil and the outer development of culture, it is necessary to have teachers who do not close themselves off with their interests in a specialised educational and teaching practice, but who place themselves with full participation in the vastness of life. Such teachers will find the possibility of awakening in young people a sense for the spiritual content of life, but no less an understanding for the practical shaping of life. With such an attitude to teaching, the fourteen- or fifteen-year-old will not be without understanding for the essentials of agriculture, industry and traffic which serve the life of humanity as a whole. The insights and skills he has acquired will enable him to feel oriented in the life that welcomes him.|298|9ff}} | ||

== Education and the members of the human being == | |||

An essential [[pedagogical law]] discovered by Rudolf Steiner is that the educator acts with his next higher [[member]] on the lower member of the child. Thus, for example, the [[etheric body]] of the educator acts on the [[physical body|physical body]] of the child, the [[astral body]] on the etheric body, etc. | |||

<div style="margin-left:20px"> | |||

„Here we are confronted with a pedagogical law which appears in all pedagogy. | |||

pedagogy. It is this, that is effective in the world upon | |||

some member of the human being, wherever it comes from, | |||

the next higher member, and that only through this does it effectively | |||

development. For the development of the physical body | |||

can be effective for the development of the physical body. | |||

Living. Only one who lives in an astral body can be effective for the development of an etheric body. | |||

a person living in an astral body. For the development of | |||

an astral body, only one living in an ego can be effective. | |||

living in an ego. And only one living in a spirit-self can be effective on an ego. | |||

living in a spirit-self. I could go on even further beyond the spirit self, but we would already | |||

beyond the spirit-self, but there we would already enter into the teaching of the esoteric. | |||

of the esoteric. | |||

What does that mean? If you become aware that in a child the etheric body is | |||

etheric body is in some way atrophied in a child, you must form your own | |||

astral body in such a way that it can have a corrective effect on the child's | |||

etheric body of the child. We can virtually say, with | |||

reference to the scheme of education, it can be written here: | |||

{|align="centre" width="400px" | |||

|- | |||

| child: || [[physical body]] || Educator: || [[etheric body]] | |||

|- | |||

| || etheric body || [[astral body]] | |||

|- | |||

|| astral body || || [[I]] | |||

|- | |||

| || I || [[spirit self]] | |||

|} | |||

The educator's own etheric body must - and this must be done through his | |||

must be able to have an effect on the physical body of the child. | |||

physical body of the child. The own astral body must be able to act on the etheric body of the child. | |||

the etheric body of the child. The educator's own ego must be able to | |||

the astral body of the child. And now you will even | |||

even be frightened inwardly, for here stands the spirit-self of the educator, | |||

which you will believe is not developed. This must have an effect on | |||

the child's ego. But the law is like that. And I will | |||

show you how far in fact, not only in the ideal educator, but often | |||

but often in the very worst educator, the spiritual self of the educator, | |||

which is not even conscious to him, acts on the child's ego. | |||

of the child. Education is indeed wrapped in a series of mysteries. | |||

of mysteries.” {{GZ||317|33f}} | |||

</div> | |||

== Literatur == | == Literatur == | ||

Revision as of 14:05, 5 July 2021

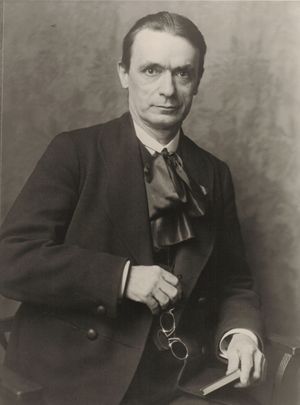

Waldorf education is a teaching and educational method developed by Rudolf Steiner, which aims to promote the free development of the unique individuality of the growing child to the best of its ability.

„A riddle of nature which he has to solve, every growing human being should be to the man who wants to be an educator.“ (Lit.:GA 52, p. 216)

Waldorf educational institutions

Waldorf education is applied and developed today primarily in the following institutions:

Waldorf education differs from many other educational methods in that it does not seek to lead the child primarily towards ready-made educational goals, but seeks to awaken the forces that - quite individually - lie dormant within the child itself.

„Waldorf education is not a pedagogical system at all, but an art to awaken what is there in the human being. Basically, Waldorf education does not want to educate, but to awaken. For today it is a question of waking up. First the teachers must be awakened, then the teachers must again awaken the children and young people.“ (Lit.:GA 217, p. 36)

Clear knowledge of the human being as the basis of education

Real art of education requires a very clear, fact-oriented knowledge of the human being and its development. Rudolf Steiner even consciously uses the comparison with the machine. Not because the human being is a machine, that is certainly not the case, but just as one must know exactly how its parts must work together in order for it to run well, so one must also recognise in the human being, with a clear, downright sober mind, quite concretely how his or her essential members (physical body, etheric body, astral body and I) best work together in order to ensure good development.

„Not general phrases, such as 'harmonious training of all powers and dispositions' and the like, can be the basis of a genuine art of education, but only on a real knowledge of the human being can such an art be built." It is not to be asserted that the phrases alluded to are incorrect, but only that nothing can be done with them, just as if one were to assert to a machine, for instance, that all its parts must be made to work harmoniously. Only those who approach it not with general phrases, but with real knowledge of the machine in detail, can handle it. Thus, for the art of education, too, it is a question of knowledge of the members of the human being and their development in detail.... One must know which part of the human being one has to influence at a certain age, and how this influence is to be done properly. There is no doubt that a truly realistic art of education, as indicated here, can only develop slowly. This is due to the way of looking at things in our time, which will continue for a long time to regard the facts of the spiritual world as the outflow of a fantastic imagination, while general, completely unreal sayings will appear to it to be the result of a realistic way of thinking. Here is to be drawn without reserve what at present will be taken by many as a fantasy painting, but what will one day be taken for granted.“ (Lit.:GA 34, p. 322f)

Promoting individuality

Even if the knowledge of the human being in general forms the necessary basis of pedagogy, every human being is unique and must therefore be supported in a completely individual way in order to develop his or her special abilities.

„Dogmas, principles and doctrines do not matter; what matters is life and the realisation of the forces which flow from selflessness and thereby from the ability to perceive the spirit.“ (Lit.:GA 52, p. 216)

The pedagogy appropriate to the growing child is to be read off again and again from the growing child itself - with the teacher's or educator's own personality being set aside as far as possible.

„An erasure of one's own personality in a certain sense is now also necessary in a single task that has infinite importance for the most everyday human life, in human education. In every growing human being, from the birth of the child, through the years of development, it is the spirit in the innermost core of the human being that is to develop; the spirit that at first rests hidden within the body, rests hidden within the soul emotions of the developing human being. If we confront this spirit, with our interests - I don't even want to say wishes and desires -, if we make the developing human being dependent on our interests, then we let our spirit flow into the human being and we basically develop what is in us in the developing human being. But I do not even want to speak of letting our wishes and desires be active in the education of a growing human being, but only of the fact that all too often, indeed that it is almost the rule, that the educator lets his intellect speak, that the educator asks his reason above all things what has to be done for this or that educational measure. In doing so, he does not take into account that he has before him a developing spirit which can only form itself according to its nature if it can develop freely and unhindered on all sides according to this nature, and if the educator gives it the opportunity for this development. We have an alien human spirit before us. We must allow an alien human spirit to have an effect on us if we are educators. As we have seen that in hypnosis, in the abnormal state, the spirit acts directly upon the human being, so in another form, when we have the child before us, the developing spirit of the child acts directly upon us and must act upon us. But this spirit will only be able to be trained by us if we are able to extinguish ourselves, just as we do in other higher pursuits, if we are able to be, without interference of our self, a servant of the human spirit entrusted to us for education, if this human spirit is given by us the opportunity to develop freely.“ (Lit.:GA 52, p. 213f)

The fundamental importance of art for Waldorf education

By its very nature, science can only grasp that which is universally valid. Art, on the other hand, arises from individual creative activity. The artistic attitude and ability are therefore particularly suited to grasping the individual nature of the child. Pedagogy in Rudolf Steiner's sense should therefore not be based one-sidedly on any kind of educational science, but should become a real art of education. Artistic creation and feeling therefore form the methodological basis of teaching in every subject, especially in those subjects which seem to have little or nothing to do with art, such as mathematics, geography, biology, chemistry, physics, etc.

„If you want to educate people with abstract scientific content, they will not experience anything of your soul. He will only experience something of his soul if you confront him artistically, because in the artistic each person must be individual, in the artistic each person is different. The scientific ideal is precisely that everyone is like everyone else. It would be a beautiful story - as they say nowadays - if everyone taught a different science. That can't be, because science is reduced to that which is the same for all people. In art, however, each person is an individuality. Through the artistic, therefore, an individual relationship of the child to the stimulating and active human being can come about, and that is necessary. It is true that in this way one does not, as in the first years of childhood, have a total physical feeling of the other human being, but one does have a total feeling of the soul of the one who stands opposite one as a guide.

Education must have soul, but as a scientist one cannot have soul. One can only have soul through what one is artistically. One can have soul if one shapes science artistically by the way one presents it, but not by the content of science as it is conceived today. Science is not an individual matter. Therefore, it does not establish a relationship between the leader and the led at the age of compulsory schooling. All teaching must be permeated by art, by human individuality, and it is the individuality of the teacher and educator that is more important than any elaborate programme. It is this that must work in the school.“ (Lit.:GA 217, p. 160)

„We cannot become educators by studying. We cannot train others to be educators, for the very reason that each of us is one. There is an educator in every human being; but this educator is asleep, he must be awakened, and the artistic is the means of awakening. When this is developed, it brings the educator as a human being closer to those he wants to lead. The person to be educated must come close to the educator as a human being, he must have something of him as a human being. It would be dreadful if someone wanted to believe that he could be an educator because he knows a lot or can "do" a lot in the sense of knowledge, which is even possible to say today.“ (S. 162)

„What I have learned has no significance at all for what I am to the child as an educator until the change of teeth. After the change of teeth, it already begins to have a certain significance. But it loses all meaning when I teach it the way I carry it inside me. It has to be translated artistically, everything has to be brought into the picture, as we shall see. I must again awaken imposing forces between myself and the child. And for the second epoch of life, for the epoch of life from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, it is much more important than the abundance of material I have learnt, much more important than what I carry in me, in my head, whether I can translate into vivid imagery, into living design, what I develop around the child and let ripple into the child. And only for those who have already passed through sexual maturity, and for these then up to the beginning of the twenties, does what one has learned oneself take on significance. For the small child up to the change of teeth, the most important thing in education is the person. For the child from the change of teeth to sexual maturity, the most important thing in education is the human being who is becoming a living artist. And it is not until the child is fourteen or fifteen years old that he or she demands for educational instruction and teaching what one has learned oneself, and this lasts until after the twentieth or twenty-first year, when the child is quite grown up - he or she is already a young lady and a young man - and when the twenty-year-old then stands opposite the other human being as an equal, even if he or she is older.“ (Lit.:GA 308, p. 22)

Especially in the period from the 7th to the 14th year of life, the artistic organisation of lessons is of essential importance for the child's development. Everything must be brought to the child in a pictorial-artistic way.

„Between the change of teeth and sexual maturity, the child is an artist, albeit in a childlike way, just as in the first epoch of life up to the change of teeth it is in a natural way a homo religiosus, a religious being. Since the child now demands to receive everything in a pictorial-artistic way, the teacher, the educator, has to face him as one who brings everything he brings to the child as an artistically formative one. This is what must be demanded of the educator and teacher of our present-day culture, what must flow into the art of education. Artistic things must take place between the change of teeth and sexual maturity between the teacher and the growing human being. In this respect, we as teachers have many things to overcome. For our civilisation and culture, which at first surround us externally, have become so that they are calculated only for the intellect, that they are not yet calculated for the artistic.“ (Lit.:GA 308, p. 37)

The three golden rules of the art of education and teaching

„Religious gratitude towards the world which reveals itself in the child, united with the awareness that the child is a divine riddle which one should solve with one's art of education. A method of education practised in love, by which the child instinctively educates itself in us, so that we do not endanger the child's freedom, which should be respected even where it is the unconscious element of the organic power of growth.

Receive the child in reverence

Educate in love

Release in freedom

“ (Lit.:GA 269, p. 179)

Pedagogy on a humanistic basis

Waldorf education is based on a view of the human being that does justice to the whole human being, which consists of body, soul and spirit, and does not fall into the one-sidedness of materialism.

„Today, when one speaks of materialism, one has the opinion that materialism is a false world view, that it is to be rejected because it is not correct. The matter is not as simple as that. Man is a soul-spiritual being, he is a bodily-physical being. But the bodily-physical is a faithful reflection of the soul-spiritual, inasmuch as we live between birth and death. And when people are so philistine in materialistic thoughts, as they became in the course of the 19th century and into the present, then the bodily-physical becomes more and more an imprint of this soul-spiritual, which itself lives in the materialistic impulses. Then it is not something wrong to say that the brain thinks, then it becomes right. By being stuck in materialism, not only are people produced who think badly of the physical, the soul and the spiritual, but people are produced who think materially and feel materially. That is to say, materialism causes man to become an automatic thinking machine, to become a being who thinks, feels and wills as a physical being. And it is not merely the task of Anthroposophy to replace a false world-view with a correct one - that is a theoretical demand - the essence of Anthroposophy today consists in striving not only for another idea, but for an act: to tear the spiritual-soul out of the physical-physical again, to lift man up into the sphere of the spiritual-soul, so that he may not be an automaton of thought, feeling and sensation. Humanity today is in danger - and some of this will be indicated in tomorrow's lecture - of losing the soul-spiritual. For that which is bodily-physically an imprint of the spiritual-soul stands today, because many people think so, because the spiritual-soul is asleep, in danger of passing over into the Ahrimanic world, and the spiritual-soul will evaporate in the universe. We are living in a time when people face the danger of losing the soul through the materialistic impulse. This is a serious matter. This fact is faced. This fact should actually become the secret today, the secret that is becoming more and more apparent, out of which we want to work fruitfully at all. You see, out of a realisation of this necessity of a turning of humanity towards a spiritual activity - not merely a change of a theory - out of this realisation such things as the didactics and pedagogy of the Waldorf School have arisen. And it is out of such a spirit that work should be done here.“ (Lit.:GA 300a, p. 163f)

In his essay "The Pedagogical Basis of the Waldorf School" Rudolf Steiner writes:

„It would be disastrous if the basic pedagogical views on which the Waldorf School is to be built were to be dominated by a spirit alien to life. Such a spirit emerges all too easily today where one develops a feeling for the part played in the disintegration of civilisation by the absorption in a materialistic attitude to life and mindset during the last decades. One would like, prompted by this feeling, to bring an idealistic attitude into the administration of public life. And whoever turns his attention to the development of education and teaching will want to see this attitude realised above all others. In such a way of thinking, much good will is manifested. It goes without saying that this should be recognised. It will, if it is exercised in the right way, be able to render valuable services when it is a question of gathering human forces for a social enterprise for which new conditions must be created. - Nevertheless, in just such a case it is necessary to point out how the best will must fail if it goes about the realisation of intentions without fully taking into account the conditions based on factual insight. This is one of the requirements that come into consideration today when founding such an institution as the Waldorf School is to be. Idealism must be at work in its pedagogical and methodological spirit; but an idealism which has the power to awaken in the growing human being the forces and abilities which he needs in the further course of his life in order to be able to work for the present human community and to have a supportive life for himself.

Pedagogy and school methodology can only fulfil such a demand with real knowledge of the growing human being. Reasonable people today demand an education and instruction which does not work towards one-sided knowledge but towards ability, not towards the mere cultivation of intellectual faculties but towards the training of the will. The correctness of this thought cannot be doubted. But one cannot educate the will and the healthy mind that underlies it if one does not develop the insights that awaken active impulses in mind and will. A mistake that is often made in this direction at the present time is not that too much insight is brought into the growing man, but that insights are cultivated that lack the impetus for life. He who believes that he can form the will without cultivating the insight that animates it is giving himself up to an illusion. - It is the task of contemporary pedagogy to see clearly on this point. This clear vision can only come from a vivid knowledge of the whole human being.

The Waldorf School, as it is provisionally conceived, will be a primary school which educates and teaches its pupils in such a way that the teaching aims and curriculum are based on the insight into the nature of the whole human being which is alive in every teacher, as far as this is already possible under present conditions. It is self-evident that the children in the individual school levels must be brought to the point where they are able to meet the requirements of today's standards. Within this framework, however, the teaching aims and curricula should be designed in such a way as they result from the knowledge of man and life.

The child is entrusted to the primary schools in a phase of life in which the state of the soul is undergoing a significant transformation. In the period from birth to the sixth or seventh year of life, the human being is predisposed to devote himself completely to the human environment closest to him for everything that needs to be educated in him, and to shape his own developing powers out of imitative instinct. From this point on, the soul becomes open to a conscious acceptance of what the educator and teacher affect the child on the basis of a self-evident authority. The child accepts this authority out of the dark feeling that something lives in the educator and teacher that should also live in him. It is impossible to be an educator or teacher without fully understanding how to relate to the child in such a way that this transformation of the instinct to imitate into the ability to appropriate, based on a self-evident relationship of authority, is taken into account in the most comprehensive sense. The conception of life of modern mankind, based on mere natural insight, does not approach such facts of human development with full consciousness. Only those who have a sense for the most subtle expressions of human life can give them the necessary attention. Such a sense must prevail in the art of education and teaching. It must shape the curriculum; it must live in the spirit that unites educator and pupils. What the educator does can only depend to a small extent on what is stimulated in him by general norms of an abstract pedagogy; rather, it must be born anew in every moment of his activity out of a living knowledge of the growing human being. Of course, one can object that such life-filled education and teaching fails in school classes with a large number of pupils. Within certain limits this objection is certainly justified; but he who makes it beyond these limits only proves that he is speaking from the point of view of an abstract normative pedagogy: for a living art of education and teaching based on a true knowledge of man is permeated with a force which stimulates sympathy in the individual pupil, so that there is no need to keep him in the matter by direct, "individual" treatment. What is done in education and teaching can be shaped in such a way that the pupil, in acquiring it, grasps it individually for himself. For this it is only necessary that what the teacher does should live sufficiently strongly. Whoever has the sense for real knowledge of the human being, the developing human being becomes to such a high degree a riddle of life to be solved by him, that he awakens in the attempted solution the co-living of the pupil. And such co-living is more fruitful than individual working, which all too easily cripples the pupil in terms of genuine self-activation. Again, within certain limits, it may be asserted that larger school classes with teachers who are full of life inspired by true knowledge of man will achieve better success than small classes with teachers who, proceeding from a standard pedagogy, are not able to develop such life.

Less pronounced, but just as important for the art of education and teaching as the transformation of the soul in the sixth or seventh year of life, is the penetrating knowledge of the human being around the time of the completion of the ninth year. There the I-feeling takes on a form which gives the child such a relationship to nature and also to other surroundings that one can speak to it more of the relations of things and processes to one another, whereas before it developed almost exclusively an interest in the relations of things and processes to man. Such facts of human development should be observed very carefully by the educator and teacher. For if one introduces into the child's world of imagination and feeling what coincides at one stage of life with the direction of the forces of development, one strengthens the whole developing human being in such a way that this strengthening remains a source of strength throughout life. If one works against the direction of development in one stage of life, one weakens the human being.

In the recognition of the special requirements of the stages of life lies the basis for an appropriate curriculum. But it is also the basis for the way in which the subject matter is dealt with in the successive stages of life. By the ninth year of life, the child must have reached a certain level in everything that has flowed into human life through cultural development. The first years of school will therefore have to be used for teaching writing and reading, and rightly so; but this teaching will have to be arranged in such a way that the essence of development finds its right in this period of life. If things are taught in such a way that the child's intellect and only an abstract acquisition of skills are called upon, the nature of will and mind will atrophy. If, on the other hand, the child learns in such a way that its whole being participates in its activity, then it develops all-round. In childlike drawing, even in primitive painting, the whole human being develops an interest in what he does. Therefore, writing should develop out of drawing. From forms in which the child's artistic sense comes to the fore, one should develop the letter forms. From an occupation which, as artistic, draws the whole human being to itself, one should develop writing, which leads to the sensible-intellectual. And only out of writing does one develop reading, which draws the attention strongly into the realm of the intellectual.

If one understands how strongly the intellectual is to be extracted from the childlike-artistic education, one will be inclined to give art the appropriate position in the first elementary school lessons. The musical and also the visual arts will be correctly placed in the field of instruction and the cultivation of physical exercises will be appropriately combined with the artistic. Gymnastics and games of movement will be made the expression of feelings stimulated by music or recitation. Eurythmic, meaningful movement will take the place of that which is based solely on the anatomy and physiology of the body. And one will find what a strong will-forming and comfort-forming power lies in the artistic shaping of the lessons. But only those teachers will be able to educate and teach in the way indicated here who, through a penetrating knowledge of the human being, see through the connection that exists between their method and the forces of development that reveal themselves in a certain stage of life. He is not a real teacher and educator who has acquired pedagogy as the science of treating children, but he in whom the pedagogue has awakened through knowledge of the human being.

It is important for the formation of the mind that the child develops its relationship to the world before it reaches the age of nine in the way that the human being is inclined to form it in an imaginative way. If the educator himself is not a fantasist, he does not make the child a fantasist either, by letting the world of plants and animals, of the air and the stars live in the child's mind in fairy-tale-like and similar representations. If, from a materialistic point of view, one wants to extend the certainly within certain limits justified visual instruction to everything possible, then one does not take into account that forces must also be developed in the human being which cannot be conveyed by visual perception alone. Thus the purely memory-like acquisition of certain things is connected with the powers of development from the sixth or seventh to the fourteenth year of life. And the teaching of arithmetic should be based on this characteristic of human nature. It can be used to cultivate the power of memory. If one does not take this into account, one will perhaps uneducationally prefer the descriptive element to the memory-forming one, especially in arithmetic lessons. One can fall into the same mistake if one anxiously strives at every opportunity to go beyond a correct measure, so that the child must understand everything that is conveyed to him. This endeavour is certainly based on good will. But it does not take into account what it means for the human being when, at a later age, he reawakens in his soul what he had acquired purely by memory in an earlier age, and now finds that, through the maturity he has attained, he now comes to an understanding of his own. It will be necessary, however, that the indifference of the pupil, which is feared when learning by memory, be prevented by the lively manner of the teacher. If the teacher is fully engaged in his teaching activity, then he can teach the child what he will later enjoy fully understanding. And in this refreshing after-experience there is always a strengthening of the purpose of life. If the teacher can work for such strengthening, then he gives the child an immeasurably great good of life to take with him on his path of existence. And in this way he will also avoid his "visual instruction" falling into banality through an excessive focus on the child's "understanding". This may take into account the child's self-activation; but its fruits are inedible after infancy; the awakening power which the living fire of the teacher kindles in the child for things which in a certain respect still lie above his "understanding" remains effective throughout life.

If one begins with descriptions of nature from the animal and plant world after the ninth year of life and holds them in such a way that the human form and the life phenomena of the human being become comprehensible from the forms and life processes of the non-human world, then one can awaken those forces in the pupil which in this period of life strive for their release from the depths of the human being. It corresponds to the character which the I-feeling assumes in this period of life to regard the animal and plant kingdoms in such a way that what in them is distributed among many types of beings in terms of qualities and activities is revealed in the human being as the summit of the living world as in a harmonious unity.

Around the twelfth year of life another turning point in human development occurs. The human being becomes ripe to develop those faculties by which he is brought in a way favourable to him to comprehend that which must be understood entirely without relation to man: the mineral kingdom, the physical world of facts, the phenomena of the weather, and so on.

How other exercises, which are a kind of working instruction, are to develop out of the cultivation of such exercises, which are formed entirely out of the nature of the human instinct for activity without regard to the aims of practical life, follows from the recognition of the nature of the stages of life. What has been indicated here for individual parts of the teaching material can be extended to everything that is to be given to the pupil up to his fifteenth year.

There is no reason to fear that the pupil will leave the primary schools in a state of mind and body alien to the outer life, if we look in the way described at that which results from the inner development of the human being as principles of instruction and education. For human life is itself formed out of this inner development, and the human being will enter this life in the best way when, through the development of his dispositions, he finds himself united with what, out of the human dispositions of the same kind, men before him have incorporated into the development of culture. However, in order to harmonise both the development of the pupil and the outer development of culture, it is necessary to have teachers who do not close themselves off with their interests in a specialised educational and teaching practice, but who place themselves with full participation in the vastness of life. Such teachers will find the possibility of awakening in young people a sense for the spiritual content of life, but no less an understanding for the practical shaping of life. With such an attitude to teaching, the fourteen- or fifteen-year-old will not be without understanding for the essentials of agriculture, industry and traffic which serve the life of humanity as a whole. The insights and skills he has acquired will enable him to feel oriented in the life that welcomes him.“ (Lit.:GA 298, p. 9ff)

Education and the members of the human being

An essential pedagogical law discovered by Rudolf Steiner is that the educator acts with his next higher member on the lower member of the child. Thus, for example, the etheric body of the educator acts on the physical body of the child, the astral body on the etheric body, etc.

„Here we are confronted with a pedagogical law which appears in all pedagogy. pedagogy. It is this, that is effective in the world upon some member of the human being, wherever it comes from, the next higher member, and that only through this does it effectively development. For the development of the physical body can be effective for the development of the physical body. Living. Only one who lives in an astral body can be effective for the development of an etheric body. a person living in an astral body. For the development of an astral body, only one living in an ego can be effective. living in an ego. And only one living in a spirit-self can be effective on an ego. living in a spirit-self. I could go on even further beyond the spirit self, but we would already beyond the spirit-self, but there we would already enter into the teaching of the esoteric. of the esoteric.

What does that mean? If you become aware that in a child the etheric body is etheric body is in some way atrophied in a child, you must form your own astral body in such a way that it can have a corrective effect on the child's etheric body of the child. We can virtually say, with reference to the scheme of education, it can be written here:

| child: | physical body | Educator: | etheric body |

| etheric body | astral body | ||

| astral body | I | ||

| I | spirit self |

The educator's own etheric body must - and this must be done through his must be able to have an effect on the physical body of the child. physical body of the child. The own astral body must be able to act on the etheric body of the child. the etheric body of the child. The educator's own ego must be able to the astral body of the child. And now you will even even be frightened inwardly, for here stands the spirit-self of the educator, which you will believe is not developed. This must have an effect on the child's ego. But the law is like that. And I will show you how far in fact, not only in the ideal educator, but often but often in the very worst educator, the spiritual self of the educator, which is not even conscious to him, acts on the child's ego. of the child. Education is indeed wrapped in a series of mysteries. of mysteries.” (Lit.:GA 317, p. 33f)

Literatur

- Stefan Leber: Die Menschenkunde der Waldorfpädagogik: Anthropologische Grundlagen der Erziehung des Kindes und Jugendlichen, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 1993, ISBN 978-3772502613

- Wilfried Gabriel: Personale Pädagogik in der Informationsgesellschaft. Berufliche Bildung, Selbstbildung und Selbstorganisation in der Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners, Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften 1995, ISBN 978-3631479124

- Michaela Strauss, Wolfgang Schad (Hrsg.): Von der Zeichensprache des kleinen Kindes: Spuren der Menschwerdung - mit menschenkundlichen Anmerkungen von Wolfgang Schad, 6. Auflage, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2007, ISBN 978-3772521348

- Ernst-Michael Kranich: Anthropologische Grundlagen der Waldorfpädagogik, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 978-3772517815

- Jost Schieren (Hrsg.): Handbuch Waldorfpädagogik und Erziehungswissenschaft, Beltz-Juventa, Weinheim - Basel 2016, ISBN 978-3-7799-3129-4

- Johannes Kiersch: Die Waldorfpädagogik: Eine Einführung in die Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3772526848; eBook ASIN B018UD710A

- Johannes Kiersch: „Mit ganz andern Mitteln gemalt“ - Überlegungen zur hermeneutischen Erschließung der esoterischen Lehrerkurse Steiners, in: Research on Steiner Education Vol.1 No.2 2010 pdf

- Ernst-Christian Demisch (Hersg.), Christa Greshake-Ebding (Hrsg.), Johannes Kiersch (Hrsg.): Steiner neu lesen: Perspektiven für den Umgang mit Grundlagentexten der Waldorfpädagogik (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 12), Peter Lang GmbH 2014, ISBN 978-3631649695, eBook ASIN B076FCC8PN

- Horst Philipp Bauer (Hrsg.), Peter Schneider (Hrsg.): Waldorfpädagogik: Perspektiven eines wissenschaftlichen Dialoges (Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge der Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 1), Peter Lang GmbH 2005, ISBN 978-3631546338

- Uwe Mingo: Leitfaden und Praxishandbuch zu Rudolf Steiners Pädagogik, Achamoth Vlg., Schönach/Bodensee 1998, ISBN 3-923302-08-8

- Frans Carlgren: Erziehung zur Freiheit. Die Pädagogik Rudolf Steiners, 11. Auflage, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2016, ISBN 978-3772516191

- Henning Kullak-Ublick: Jedes Kind ein Könner: Fragen und Antworten zur Waldorfpädagogik, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2017, ISBN 978-3772528736, eBook ASIN B073SDDWT9

- Gerhard Wehr: Der pädagogische Impuls Rudolf Steiners. Theorie und Praxis der Waldorfpädagogik, Fischer-TB, Frankfurt a.M. 1983, ISBN 3-596-25521-X

- Heinz Brodbeck (Hrsg.), Robert Thomas (Hrsg.): Steinerschulen heute: Ideen und Praxis der Waldorfpädagogik, Zbinden Verlag 2019, ISBN 978-3859894549

- Tobias Richter (Hrsg.): Pädagogischer Auftrag und Unterrichtsziele - vom Lehrplan der Waldorfschule, 4. Auflage, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3772526695, eBook ASIN B01N1I5NCE

- Rüdiger Blankertz: 'Das Erfolgsmodell' Waldorfschule und 'das Problem' Rudolf Steiner, Edition Nadelöhr 2019, ISBN 978-3952508015

- Valentin Wember: Was will Waldorf wirklich? Die unbekannte Erziehungskunst Rudolf Steiners. Ein Vortrag für Eltern und Lehrer. Stratosverlag 2019, ISBN 9783943731286

- Rudolf Steiner

- Rudolf Steiner: Spirituelle Seelenlehre und Weltbetrachtung, GA 52 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-0520-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Westliche und östliche Weltgegensätzlichkeit, GA 83 (1981), ISBN 3-7274-0830-8 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Geistige Wirkenskräfte im Zusammenleben von alter und junger Generation. Pädagogischer Jugendkurs., GA 217 (1988), ISBN 3-7274-2170-3 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Ritualtexte für die Feiern des freien christlichen Religionsunterrichtes und das Spruchgut für Lehrer und Schüler der Waldorfschule, GA 269 (1997), ISBN 3-7274-2690-X Template:Lectures 1

- Rudolf Steiner: Idee und Praxis der Waldorfschule, GA 297 (1998), ISBN 3-7274-2970-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Rudolf Steiner in der Waldorfschule, GA 298 (1980) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Konferenzen mit den Lehrern der Freien Waldorfschule 1919 bis 1924, Band I: Ausführliche Einleitung (E. Gabert) / Konferenzen 1919–1921, GA 300a (1995), ISBN 3-7274-3000-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die gesunde Entwickelung des Menschenwesens. Eine Einführung in die anthroposophische Pädagogik und Didaktik., GA 303 (1978), ISBN 3-7274-3031-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die pädagogische Praxis vom Gesichtspunkte geisteswissenschaftlicher Menschenerkenntnis. Die Erziehung des Kindes und jüngeren Menschen., GA 306 (1956) English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Methodik des Lehrens und die Lebensbedingungen des Erziehens, GA 308 (1986), ISBN 3-7274-3080-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Heilpädagogischer Kurs, GA 317 (1995), ISBN 3-7274-3171-7 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |

- Kritische Literatur

- Klaus Prange: Erziehung zur Anthroposophie: Darstellung und Kritik der Waldorfpädagogik, 3. Auflage, Klinkhardt 2000, ISBN 978-3781510890

- Sybille-Christin Jacob, Detlef Drewes: Aus der Waldorfschule geplaudert: Warum die Steiner-Pädagogik keine Alternative ist, 2. Auflage, Alibri Verlag 2004, ISBN 978-3932710841

- Heiner Ullrich: Waldorfpädagogik: Eine kritische Einführung, Beltz Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3407257215; eBook ASIN: B010U1P15C

- Hellmich, Achim und Teigeler, Peter (Hrsg.): Montessoripädagogik, Freinetpädagogik, Waldorfpädagogik - Konzeption und aktuelle Praxis. Beltz Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3407252188