Artificial intelligence: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

The term "artificial intelligence" was first used in 1955 by the logician and computer scientist John McCarthy (1927-2011) in his grant proposal[3] for the six-week ''Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence'', which he organised and began on 13 July 1956 at [[w:Dartmouth College|Dartmouth College]] in [[w:Hanover (New Hampshire)|Hanover]]. [[w:Marvin Minsky|Marvin Minsky]], [[w:Nathan Rochester|Nathan Rochester]] and [[w:Claude Shannon|Claude Shannon]], among others, also took part in this conference. The ''Dartmouth Conference'' has since been regarded as the founding event of research in the field of AI. | The term "artificial intelligence" was first used in 1955 by the logician and computer scientist John McCarthy (1927-2011) in his grant proposal[3] for the six-week ''Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence'', which he organised and began on 13 July 1956 at [[w:Dartmouth College|Dartmouth College]] in [[w:Hanover (New Hampshire)|Hanover]]. [[w:Marvin Minsky|Marvin Minsky]], [[w:Nathan Rochester|Nathan Rochester]] and [[w:Claude Shannon|Claude Shannon]], among others, also took part in this conference. The ''Dartmouth Conference'' has since been regarded as the founding event of research in the field of AI. | ||

Based on the work of [[w:Alan Turing|Alan Turing]] (1912-1954), including the essay "''Computing machinery and intelligence''", [[w:Allen Newell|Allen Newell]] (1927-1992) and [[w:Herbert A. Simon|Herbert A. Simon]] (1916-2001) from [[w:Carnegie Mellon University|Carnegie Mellon University]] in [[w:Pittsburgh|Pittsburgh]] formulated the "Physical Symbol System Hypothesis", according to which [[thinking]] is information processing, and information processing is a computing process, a manipulation of symbols. Thinking does not depend on the brain as such: "Intelligence is mind implemented by any patternable kind of matter." | Based on the work of [[w:Alan Turing|Alan Turing]] (1912-1954), including the essay "''Computing machinery and intelligence''", [[w:Allen Newell|Allen Newell]] (1927-1992) and [[w:Herbert A. Simon|Herbert A. Simon]] (1916-2001) from [[w:Carnegie Mellon University|Carnegie Mellon University]] in [[w:Pittsburgh|Pittsburgh]] formulated the "Physical Symbol System Hypothesis", according to which [[thinking]] is information processing, and information processing is a computing process, a manipulation of symbols. Thinking does not depend on the brain as such: "''Intelligence is mind implemented by any patternable kind of matter.''" | ||

This view that intelligence is independent of the carrier substance is shared by the proponents of the strong AI thesis. For [[w:Marvin Minsky|Marvin Minsky]] (1927-2016) of the [[w:Massachusetts Institute of Technology|Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] (MIT), one of the pioneers of AI, "the goal of AI is to overcome death". In his book ''Mind Children'', the robotics specialist [[w:Hans Moravec|Hans Moravec]] (* 1948) from [[w:Carnegie Mellon University|Carnegie Mellon University]] describes the scenario of the evolution of post-biological life: a robot transfers the knowledge stored in the human brain to a computer, so that the biomass of the brain becomes superfluous and a posthuman age begins in which the stored knowledge remains accessible for as long as desired. With the detailed memory of everything humans have ever thought, our "brainchildren" with their superior intelligence would then face greater challenges in the vastness of the universe: | |||

{{Quote|What awaits is not oblivion but rather a future which, from our present vantage point, is best described by the words "postbiological" or even "supernatural." It is a world in which the human race has been swept away by the tide of cultural change, usurped by its own artificial progeny. The ultimate consequences are unknown, though many intermediate steps are not only predictable but have alread been taken. Today, our machines are still simple creations, requiring the parental care and hovering attention of any newborn, hardly worthy of the word "intelligent." But within the next century they will mature into entities as complex as ourselves, and eventually into something transcending everything we know - in whom we can take pride when they refer to themselves as our descendants. | |||

Unleashed from the plodding pace of biological evolution, the children of our minds will be free to grow to confront immense and fundamental challenges in the larger universe. We humans will benefit for a time from their labors, but sooner or later, like natural children, they will seek their own fortunes while we, their aged parents, silently fade away. Very little need be lost in this passing of the torch - it will be in our artificial offspring's power, and to their benefit, to remember almost everything about us, even, perhaps, the detailed working of individual human minds.|Hans Moravec|''Mind Children. The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence'', p. 1}} | |||

The AI pioneer [[w:Raymond Kurzweil|Raymond Kurzweil]] (* 1948), head of technical development at [[w:Google|Google]] since 2012, expects that in 2029 a computer will pass the so-called [[w:Turing Test|Turing Test]] for the first time and that artificial intelligence will reach human levels and soon surpass them. The possibility of such a superintelligence and an associated "intelligence explosion" was first speculated about in 1965 by the British mathematician and cryptologist [[w:Irving John Good|Irving John Good]] (1916-2009), who had worked under the direction of [[w:Alan Turing|Alan Turing]] on decoding the radio traffic of the German navy: | |||

{{Quote|Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an „intelligence explosion“, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.|Irving John Good|''Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine'' [https://exhibits.stanford.edu/feigenbaum/catalog/gz727rg3869 online]}} | |||

== Literature == | == Literature == | ||

Revision as of 15:35, 29 August 2021

And such a brain that shall think accurately,

Will henceforth also make a thinker

[[

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a branch of computer science that aims to automate intelligence by means of computers. Particularly in the field of cognitive intelligence (e.g. speech and text recognition, object recognition, autonomous driving), great progress has been made in recent years.

History

The term "algorithm" is named after the polymath al-Khwarizmi ("the native of Khwarazm", Latin: Algorismi; * around 780; † between 835 (?) and 850), who came from Khwarazm in Iran and worked and taught in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad during the heyday of the Abbasids. An algorithm is a "systematic, logical rule or procedure consisting of a finite number of well-defined individual steps that leads to the solution of a given problem"[1]. These can be rules of all kinds, for example rules of calculation, recipes (including cooking recipes), laws and regulations, etc. They can be formulated unambiguously in human language and implemented in computer programs in a strictly formalised way. In the early phase of AI, attempts were made to emulate human intelligence by means of corresponding algorithms.

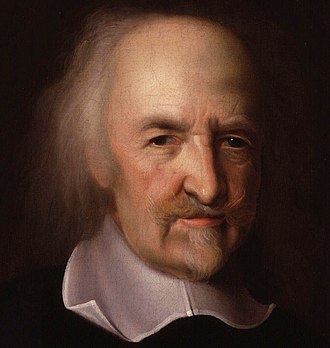

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) already advocated an early version of computationalism, according to which man's rational mind is based on computational processes:

„By RATIOCINATION, I mean computation. Now to compute, is either to collect the sum of many things that are added together, or to know what remains when one thing ist taken out of anaother. Ratiocination, therefore, is the same with addition and subtraction; and if any man add multiplication and division, I will not be against it, seeing multiplication is nothing but addition of equals one to another, and division nothing but a subtraction of equals one from another, as often as is possible. So that all ratiocination is comprehended in these two operations of the mind, addition and subtraction.“

The possibility of automating or mechanically reproducing human intelligence had already been considered by Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709-1751) in his major work L'Homme Machine, published anonymously in 1748.

„In de la Mettrie's Man, a Machine, a world conception appears that is so overwhelmed by the picture of nature that it can admit only nature as valid. What occurs in the self-consciousness must, therefore, be thought of in about the same way as a mirror picture that we compare with the mirror. The physical organism would be compared with the mirror, the self-consciousness with the picture. The latter has, apart from the former, no independent significance. In Man, a Machine, we read:

'If, however, all qualities of the soul depend so much on the specific organization of the brain and the body as a whole that they obviously are only this organization itself, then, in this case, we have to deal with a very enlightened machine. . . . ‘Soul,’ therefore, is only a meaningless expression of which one has no idea (thought picture), and that a clear head may only use in order to indicate by it the part in us that thinks. Just assume the simplest principle of motion and the animated bodies have everything they need in order to move, feel, repeat, in short, everything necessary to find their way in the physical and moral world. . . . If whatever thinks in my brain is not a part of this inner organ, why should my blood become heated when I make the plan for my works or pursue an abstract line of thought, calmly resting on my bed?' (Compare de la Mettrie, Der Mensch eine Maschine, Philosophische Bibliothek, Vol. 68.)“ (Lit.:GA 18, p. 121f)

Laplace's demon, which Pierre-Simon Laplace designed as a thought model and was later named after him, and which is based on the idea that the entire universe, including human intelligence, resembles a giant clockwork, also points in this direction.

As early as 1948, Norbert Wiener (1894-1964), who coined the term cybernetics, had already suggested:

„The mechanical brain does not secrete thought "as the liver does bile," as the earlier materialists claimed, nor does it put it out in the form of energy, as the muscle puts out its activity. Information is information, not matter or energy. No materialism which does not admit this can survive at the present day.“

The term "artificial intelligence" was first used in 1955 by the logician and computer scientist John McCarthy (1927-2011) in his grant proposal[3] for the six-week Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, which he organised and began on 13 July 1956 at Dartmouth College in Hanover. Marvin Minsky, Nathan Rochester and Claude Shannon, among others, also took part in this conference. The Dartmouth Conference has since been regarded as the founding event of research in the field of AI.

Based on the work of Alan Turing (1912-1954), including the essay "Computing machinery and intelligence", Allen Newell (1927-1992) and Herbert A. Simon (1916-2001) from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh formulated the "Physical Symbol System Hypothesis", according to which thinking is information processing, and information processing is a computing process, a manipulation of symbols. Thinking does not depend on the brain as such: "Intelligence is mind implemented by any patternable kind of matter."

This view that intelligence is independent of the carrier substance is shared by the proponents of the strong AI thesis. For Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), one of the pioneers of AI, "the goal of AI is to overcome death". In his book Mind Children, the robotics specialist Hans Moravec (* 1948) from Carnegie Mellon University describes the scenario of the evolution of post-biological life: a robot transfers the knowledge stored in the human brain to a computer, so that the biomass of the brain becomes superfluous and a posthuman age begins in which the stored knowledge remains accessible for as long as desired. With the detailed memory of everything humans have ever thought, our "brainchildren" with their superior intelligence would then face greater challenges in the vastness of the universe:

„What awaits is not oblivion but rather a future which, from our present vantage point, is best described by the words "postbiological" or even "supernatural." It is a world in which the human race has been swept away by the tide of cultural change, usurped by its own artificial progeny. The ultimate consequences are unknown, though many intermediate steps are not only predictable but have alread been taken. Today, our machines are still simple creations, requiring the parental care and hovering attention of any newborn, hardly worthy of the word "intelligent." But within the next century they will mature into entities as complex as ourselves, and eventually into something transcending everything we know - in whom we can take pride when they refer to themselves as our descendants. Unleashed from the plodding pace of biological evolution, the children of our minds will be free to grow to confront immense and fundamental challenges in the larger universe. We humans will benefit for a time from their labors, but sooner or later, like natural children, they will seek their own fortunes while we, their aged parents, silently fade away. Very little need be lost in this passing of the torch - it will be in our artificial offspring's power, and to their benefit, to remember almost everything about us, even, perhaps, the detailed working of individual human minds.“

The AI pioneer Raymond Kurzweil (* 1948), head of technical development at Google since 2012, expects that in 2029 a computer will pass the so-called Turing Test for the first time and that artificial intelligence will reach human levels and soon surpass them. The possibility of such a superintelligence and an associated "intelligence explosion" was first speculated about in 1965 by the British mathematician and cryptologist Irving John Good (1916-2009), who had worked under the direction of Alan Turing on decoding the radio traffic of the German navy:

„Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an „intelligence explosion“, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.“

Literature

- The English works of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury Vol I. Now first collected and edited by Sir William Molesworth. John Bohn London 1839 archive.org

- Thomas Hobbes: Elemente der Philosophie. Erste Abteilung: Der Körper. Übers. u. hrsg. v. Karl Schuhmann. Meiner, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 978-3-7873-1459-1.

- Tom Stonier: Beyond Information: The Natural History Of Intelligence. Springer 1992, ISBN 978-3540196549

- Ray Kurzweil: KI - Das Zeitalter der künstlichen Intelligenz, Carl Hanser Verlag 1993, ISBN 978-3446173750

- John Searle: Die Wiederentdeckung des Geistes, Artemis & Winkler, München 1993, ISBN 978-3760819440

- Marvin Minsky: The Society of Mind: Mentopolis, Klett-Cotta 1994, ISBN 978-3608931174

- Hernan Riquelme: Information Processing Theory and its Explanation of the Creative Process, in: Creativity and Innovation Management, Volume 3, Number 2, June 1994 academia.edu

- Roger Penrose: Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness, Vintage Books, London 1995, ISBN 978-0099582113

- Hans Moravec: Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence, Harvard University Press 1998, ISBN 978-0674576162

- Hans Moravec: Computer übernehmen die Macht. Vom Siegeszug der künstlichen Intelligenz, Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 978-3455085754

- Wolfgang Ziegler: Neuronale Netze, entwickler.press, eBook ASIN B0105UIJPC

- Jeff Hawkins: Die Zukunft der Intelligenz: Wie das Gehirn funktioniert und was Computer davon lernen können, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2006, ISBN 978-3499621673

- Bernd Vowinkel: Maschinen mit Bewusstsein - Wohin führt die künstliche Intelligenz?, Wiley-VCH 2006, ISBN 978-3527406302, eBook ASIN B0096QYU4G

- Johannes Grössl: Ist das Gehirn ein Computer - Gödels Unvollstaendigkeitssatz als Funktionalismuskritik. Diplomarbeit an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München 2009 academia.edu

- Ray Kurzweil: Das Geheimnis des menschlichen Denkens: Einblicke in das Reverse Engineering des Gehirns, Lola Books 2014, ISBN 978-3944203065, eBook ASIN B01348W39K

- Ray Kurzweil: Menschheit 2.0: Die Singularität naht, Lola Books 2014, ISBN 978-3944203089, eBook ASIN B0112F25QI

- Ray Kurzweil: Die Intelligenz der Evolution, KiWi-Taschenbuch 2016, ISBN 978-3462049428, Kiepenheuer & Witsch eBook, ASIN B01FENJJH2

- Nick Bostrom: Superintelligenz: Szenarien einer kommenden Revolution, Suhrkamp Verlag 2016, ISBN 978-3518586846, eBook ASIN B00OTQKXJE

- Klaus Mainzer: Künstliche Intelligenz – Wann übernehmen die Maschinen? Springer Verlag 2016, ISBN 978-3662484524, eBook ASIN B01CYJHR1Y

- Wolfgang Ertel: Grundkurs Künstliche Intelligenz, Springer-Verlag 2016, ISBN 978-3-658-13548-5, eBook ISBN 978-3-658-13549-2

- Pedro Domingos: The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World, Penguin 2017, ISBN 978-0141979243, eBook ASIN B06XK8D37J

- Christian J. Meier: Suppenintelligenz (TELEPOLIS): Die Rechenpower aus der Natur, Heise Medien GmbH & Co. KG 2017, ISBN 978-3957881014, eBook ASIN B076CQBPMC

- Julian Nida-Rümelin, Nathalie Weidenfeld: Digitaler Humanismus: Eine Ethik für das Zeitalter der Künstlichen Intelligenz, Piper 2018, ISBN 978-3492058377, eBook ASIN B07GZPD34T

- Toby Walsh: It's alive: Wie künstliche Intelligenz unser Leben verändern wird, Edition Körber 2018, ISBN 978-3896842664, eBook ASIN B07GWHS12N

- Thomas Ramge, Dinara Galieva (Illustrator): Mensch und Maschine: Wie künstliche Intelligenz und Roboter unser Leben verändern, Reclam Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3150194997, eBook ASIN B077TT4283

- Peter Fischer: Künstliche Intelligenz: Digitalisierung, neuronale Programmierung, Industrie 4.0 & Deep learning, Independently published 2018, ISBN 978-1728834597, eBook ASIN B07JGFX5ZL

- Andrew McAfee, Erik Brynjolfsson: The Second Machine Age: Wie die nächste digitale Revolution unser aller Leben verändern wird, Plassen Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3864705946; eBook ASIN B00NLFE9V2

- Michel Troublé: Consciousness, artificial intelligence. Transhumanism: truths and false promises, 2019 academia.edu

- Richard David Precht: Jäger, Hirten, Kritiker: Eine Utopie für die digitale Gesellschaft, Goldmann Verlag 2018, ISBN 978-3442315017; eBook ASIN B078ZYCFXC

- Richard David Precht: Künstliche Intelligenz und der Sinn des Lebens, Goldmann Verlag 2020, ISBN 978-3442315611; eBook ASIN B07ZTGNX3G

- Hans Bonneval: Revolution im Denken: Rudolf Steiner. Warum Computer nicht denken können, BoD, Norderstedt 2017

- Paul Emberson: Maschinen und Menschengeist, The DewCross Centre for Moral Technology, Edinburgh 2013

- Paul Emberson: Von Gondishapur bis Silicon Valley Band I, Etheric Dimensions Press, Schweiz und Schottland 2012 - kritische Betrachtung: A well intended very flawed Book

- Paul Emberson: From Gondishapur to Silicon Valley, Volume II, Etheric Dimensions Press, Switzerland and Scottland 2014 (deutsche Übersetzung in Vorbereitung)

- Mieke Mosmuller: Singularität - Dialoge über künstliche Intelligenz und Spiritualität, Occident Verlag 2019, ISBN 978-3946699101

- Nicanor Perlas, Sebastian Lorenz (Übers.): Der letzte Kampf der Menschheit? Die Antwort der Geisteswissenschaft auf die Künstliche Intelligenz, Urachhaus Verlag, November 2020, ISBN 978-3825152352

- Edwin Hübner: Menschlicher Geist und Künstliche Intelligenz: Die Entwicklung des Humanen inmitten einer digitalen Welt, Verlag Freies Geistesleben 2020, ISBN 978-3772529559: eBook B08PPWV9GF ASIN B08PPWV9GF

- Rudolf Steiner, Andreas Neider (Hrsg.): Der elektronische Doppelgänger und die Entwicklung der Computertechnik, Futurum Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3856363642; Kindle Edition 2015, ASIN B0195VK6WG

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Rätsel der Philosophie in ihrer Geschichte als Umriß dargestellt, GA 18 (1985), ISBN 3-7274-0180-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Anthroposophische Leitsätze, GA 26 (1998), ISBN 3-7274-0260-1 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Tempellegende und die Goldene Legende , GA 93 (1991), ISBN 3-7274-0930-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Gegenwärtiges und Vergangenes im Menschengeiste, GA 167 (1962), ISBN 3-7274-1670-X English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die spirituellen Hintergründe der äußeren Welt. Der Sturz der Geister der Finsternis, GA 177 (1999), ISBN 3-7274-1771-4 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Individuelle Geistwesen und ihr Wirken in der Seele des Menschen, GA 178 (1992), ISBN 3-7274-1780-3 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

- Rudolf Steiner: Die Verantwortung des Menschen für die Weltentwickelung durch seinen geistigen Zusammenhang mit dem Erdplaneten und der Sternenwelt, GA 203 (1989), ISBN 3-7274-2030-8 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |

References

- ↑ Werner Stangl: Algorithmus. In: lexikon.stangl.eu. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ Norbert Wiener: Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, MIT Press 1948, p. 132