Sensual-moral effect of color

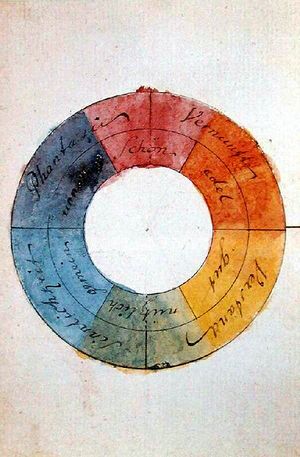

The sensual-moral effect of color is described in "Zur Farbenlehre" (On the Theory of Colour), published by Goethe in 1810. Goethe shows there how every perception of color is accompanied by a quite characteristic, by no means accidental undertone of feeling, which is initially experienced only very subliminally, but can be brought more clearly into consciousness by increased attention. For this purpose, however, it must be separated from the purely personally conditioned and often much more prominent sympathy and antipathy that one feels for a certain color. This is best achieved when one exposes oneself to the pure color effect out of a completely conscious willful decision and fades out all other, disturbing external and internal influences.

„To feel these individual, significant effects completely, one must surround the eye completely with a color, e.g. be in a monochromatic room, look through a colored glass. One then identifies with the color; it harmonizes the eye and mind with itself.“

Although this fine undertone of the externally perceived color can only be experienced subjectively inwardly mentally by the observer, it nevertheless does not depend on the observer's personal idiosyncrasy and insofar has at the same time an objective character. Certain color combinations arouse quite specific mental effects. These are of decisive importance for the artistic handling of color.

„Since color occupies such a high place in the series of primordial natural phenomena, filling the simple circle allotted to it with decided variety, we shall not be surprised to learn that it affects the sense of the eye, to which it is especially adapted, and through its mediation on the mind in its most general elementary phenomena, without reference to the nature or form of a material, on the surface of which we perceive it, it produces individually a specific, in combination a partly harmonious, partly characteristic, often also inharmonious, but always a decisive and significant effect, which is directly connected to the moral. Therefore color, considered as an element of art, can be used for the highest aesthetic purposes.“

„Da die Farbe in der Reihe der uranfänglichen Naturerscheinungen einen so hohen Platz behauptet, indem sie den ihr angewiesenen einfachen Kreis mit entschiedener Mannigfaltigkeit ausfüllt, so werden wir uns nicht wundern, wenn wir erfahren, dass sie auf den Sinn des Auges, dem sie vorzüglich zugeeignet ist, und durch dessen Vermittelung auf das Gemüt in ihren allgemeinsten elementaren Erscheinungen, ohne Bezug auf Beschaffenheit oder Form eines Materials, an dessen Oberfläche wir sie gewahr werden, einzeln eine spezifische, in Zusammenstellung eine teils harmonische, teils charakteristische, oft auch unharmonische, immer aber eine entschiedene und bedeutende Wirkung hervorbringe, die sich unmittelbar an das Sittliche anschließt. Deshalb denn Farbe, als ein Element der Kunst betrachtet, zu den höchsten ästhetischen Zwecken mitwirkend genutzt werden kann.“

The actual perception of color and the accompanying emotional undertone are inseparably connected and arise as a whole from the essence of the respective color.

„Goethe starts from the physiological colors; I have shown you this when I characterized his way of coming to knowledge by other methods of investigation than the present methods of investigation. Then, however, his whole approach culminates in the chapter which he called "Sensual-moral effect of color". There Goethe goes, so to speak, directly from the physical into the spiritual, and he then characterizes the whole spectrum of colors with an extraordinary accuracy. He characterizes the impression that is experienced; it is, after all, something that is experienced quite objectively. Even if it is experienced in the subject, it is nevertheless something thoroughly objectively experienced in the subject, the impression which, let us say, the colors situated towards the warm side of the spectrum make, red, yellow. He describes them in their activity, how they, so to speak, have an exciting or stimulating effect on man. And he describes how then the colors which are situated towards the cold side have a stimulating effect, incite to devotion; and he describes how the green in the middle has a balancing effect.

So, in a sense, he is describing a spectrum of feelings. And it is interesting to visualize, how a soul-differentiated immediately jumps out of the ordered physical way of looking at things. Whoever understands such a course of investigation comes to the following results. He says to himself: The individual colors of the spectrum stand before us, they are experienced as entities which appear to be quite separate from man. In the ordinary perception of life we quite naturally and justifiably attach the greatest importance to directly grasping this objective element, let us say in the red, in the yellow. But there is an undertone everywhere. If we look at the immediate experience, it can only be separated in abstraction from that which is a so-called experience of the red nuance and the blue nuance, separated from the human being externally, in an objective sense; It is an abstract separation from that which is also directly experienced in the act of seeing, but which is only struck, which is, so to speak, experienced in a quiet undertone, but which can never remain away, so that in this field one can only look at it purely physically, if one first abstracts that which is experienced mentally from the physical.

So we have first the outer spectrum, and we have at this outer spectrum the undertone of the mental experiences. So we stand with our senses, with the eye, opposite the outer world, and we cannot adjust the eye in any other way than that mostly, even if often even unconsciously or subconsciously, soul experience runs along with it. We call what is experienced through the eye sensation. We are now accustomed, my dear present ones, to call that which is experienced at the sensation, which is experienced soulishly - at which a stimulus, which originates from the objectively spread out, presents itself as sensation - the subjective. But you see from the way in which I have just presented this, following Goethe, that we can, so to speak, set up a counter-spectrum, a soul counter-spectrum, which can be brought into parallel quite exactly with the outer optical spectrum.“ (Lit.:GA 73a, p. 254ff)

Literature

- Olaf L. Müller: Mehr Licht: Goethe mit Newton im Streit um die Farben, S. Fischer Verlag, ISBN 978-3100022073, eBook ASIN B00OVFTIXU

- Rudolf Steiner: Fachwissenschaften und Anthroposophie, GA 73a (2005), ISBN 3-7274-0735-2 English: rsarchive.org German: pdf pdf(2) html mobi epub archive.org

|

References to the work of Rudolf Steiner follow Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works (CW or GA), Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach/Switzerland, unless otherwise stated.

Email: verlag@steinerverlag.com URL: www.steinerverlag.com. Index to the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner - Aelzina Books A complete list by Volume Number and a full list of known English translations you may also find at Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works Rudolf Steiner Archive - The largest online collection of Rudolf Steiner's books, lectures and articles in English. Rudolf Steiner Audio - Recorded and Read by Dale Brunsvold steinerbooks.org - Anthroposophic Press Inc. (USA) Rudolf Steiner Handbook - Christian Karl's proven standard work for orientation in Rudolf Steiner's Collected Works for free download as PDF. |